Volatility – it is sometimes said – takes the elevator up but takes the stairs down. Like seismic activity, volatility can rise precipitously, but tends to decay more slowly; aftershocks and tremors continue to roil markets after any major repricing occurs. The practical consequence is that, once the markets become volatile, they tend to remain so for some time. For the short term at least, outsized daily moves will be the new normal.

Exhibit 1: Large Swings Have Become Commonplace

Prior to this month, the last time that the Dow Jones Industrial Average® moved by 5% in a single day was almost 11 years ago. However, the Dow has swung that much (or more) nearly every day in March, including a single-day decline of 12% on Monday that marked its worst day since the infamous “Black Monday” of 1987. How long might this continue?

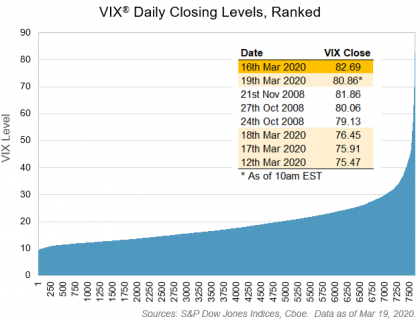

Sometimes called the market’s “fear gauge”, Cboe’s Volatility Index, better known as VIX®, gives an indication of how much volatility the market expects in the near term (or, more accurately, the level of volatility that would justify the current prices of S&P 500® options). In a history that stretches back over 7,500 trading days to January 1990, five of the eight highest closing levels for VIX occurred in the past week. Only the peaks in volatility that occurred during the 2008 financial crisis saw anything similar.

Exhibit 2: Five of the highest-ever closes in VIX occurred in the last week.

What does a VIX of 80 mean? In the simplest possible terms, it means that the market expects daily moves in the equity markets to be around four times larger than normal. Over its long history, the S&P 500 has moved a little under 1% each day, on average. With VIX currently standing at four times its long-term average of 20, daily moves in the S&P 500 of around 4% are implied for the next month.

Further, VIX is a forward looking measure, based on traded prices of listed options and with a 30-day horizon for its prediction. VIX also encodes the expectation that volatility – once elevated – is likely to revert to its average, eventually. Accordingly, in the very short term, moves of more than 4% should be expected. Confirming the point, Cboe’s measure of volatility expectations for the next week (the VSXT index) has an index level of 96 (at time of writing), meaning that over the next few trading days, 5% moves in the S&P 500 are the “new normal”.

(For a more in-depth explanation of what information may be usefully discerned from a given VIX level, see our earlier paper, “A Practitioner’s Guide to Reading VIX”)

Beyond the U.S. equity market, indices using the same methodology that VIX uses to reflect S&P 500 volatility expectations have been developed for a range of global indices. Many of these global volatility indicators are currently indicating similar levels of record-high uncertainty. Volatility indicators for crude oil and U.S. Treasury bonds made record closing highs yesterday. Check out the latest readings in S&P DJI’s most recent Risk and Volatility Dashboard.

Further Reading:

- S&P DJI Risk and Volatility Dashboard, March 18 2020

- Edwards, Lazzara & Preston, A Practitioner’s Guide to Reading VIX (2017)

- Indexology posts: Volquakes and The Essence of VIX