A new paper published today provides a new perspective on the active usage of products linked to S&P DJI indices, and illustrates the network of liquidity that has developed around the S&P 500® and other popular benchmarks.

“Active” and “passive” are colloquial terms, and it can be hard to distinguish one from the other at times. A portfolio replicating a broad, capitalization-weighted index is the archetypal passive strategy, yet timing the market by buying and selling such a portfolio on a daily basis would qualify under most definitions of active investing.

Seeking for a precise definitional distinction between active and passive investments may be a distraction: some investors will trade more frequently than others, nearly all will adjust their positions over time. What is needed is a sense of not whether an investment strategy is active, but how much activity occurs.

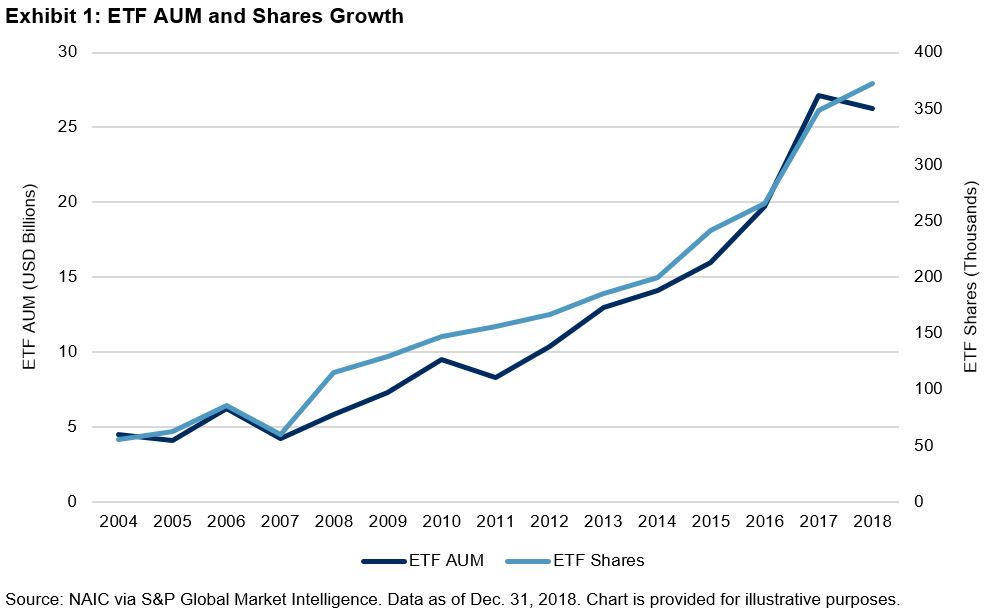

Exchange-traded funds (ETFs) illustrate the point. An ETF tracking the S&P 500 is likely to be passively managed by the fund’s sponsor, but may have active owners who trade in and out of their positions frequently. Futures and options seem easier to classify: with their predetermined expiry dates, they are built to serve shorter-term needs. Yet such products can be used to replicate passive portfolio performance, potentially for years or decades if positions are rolled.

A Window on Index Liquidity

Our new research provides a snapshot of trading volumes associated with the range of tradeable products linked to S&P DJI indices – including futures, ETFs, options and other listed products. These statistics begin to fill in some of the gaps in our understanding of the active use of ‘passive’ products, enabling us to infer average holding periods, or map out where liquidity may be found.

The data range over 1,300 individual products linked to 500 different indices, traded in more than 30 countries. With annual volumes in the trillions of U.S. dollars for more popular indices, one conclusion of the research is that active investors play a major role in products linked to S&P DJI’s indices: average holding periods of a few months or less are typical.

The S&P 500 Ecosystem

Since the launch of index options and futures in the 1980s, followed by ETFs in the 1990s, the S&P 500 index has provided the basis for investors to access a growing range of exposures. And – while several of our indices are associated to significant trading – the S&P 500 stands apart.

Over time, a S&P 500 ‘trading ecosystem’ has developed, with links extending across different product lines such as futures and options, and different—but related—indices such sectors, factors (“smart beta”) and other derivatives of the parent index. The paper illustrates this network, and the value of associated trading in billions of U.S. dollars in the 12 months ending June 30, 2019.

The S&P 500 Ecosystem – Index Equivalent Trading Volume in Billions of U.S. Dollars

The proportion of assets managed ‘passively’ has become a much-debated statistic, particularly for large-cap U.S. equities. But some of the universe putatively owned by passive investors may be mislabelled. Click here to read the full report.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.

Why is implied volatility normally higher than realized? From a behavioral finance perspective, this is an indication of risk aversion—investors are willing to pay a premium to buy protection against risk. From an option pricing perspective, it is because stocks and stock indices do not follow the log-normal distribution assumption of Black-Scholes. The empirical distribution of stock returns has a negative skew and hence reflects larger losses than a normal or log-normal model using the ex-post mean and standard deviation would predict. Implied volatility takes into account large but rare events, while realized volatility will only include such events if they have occurred in the look-back calculation period. Since low-probability events are rare by definition, realized volatility tends to understate the potential for large losses most of the time. However, in a distressed market, realized volatility tends to overstate the risk of large losses when these sudden moves indeed occurred in the calculation window.

Why is implied volatility normally higher than realized? From a behavioral finance perspective, this is an indication of risk aversion—investors are willing to pay a premium to buy protection against risk. From an option pricing perspective, it is because stocks and stock indices do not follow the log-normal distribution assumption of Black-Scholes. The empirical distribution of stock returns has a negative skew and hence reflects larger losses than a normal or log-normal model using the ex-post mean and standard deviation would predict. Implied volatility takes into account large but rare events, while realized volatility will only include such events if they have occurred in the look-back calculation period. Since low-probability events are rare by definition, realized volatility tends to understate the potential for large losses most of the time. However, in a distressed market, realized volatility tends to overstate the risk of large losses when these sudden moves indeed occurred in the calculation window.