The S&P Pure Style Indices select and weight securities based on their style scores, unlike the traditional S&P Style Indices. In our previous blog post, we demonstrated that differences in index construction play a major role in the performance differential between the S&P Style Indices and the S&P Pure Style Indices. We estimated that the differences in style purity and weight scheme mostly contributed positively to the excess returns of pure style indices over style indices.

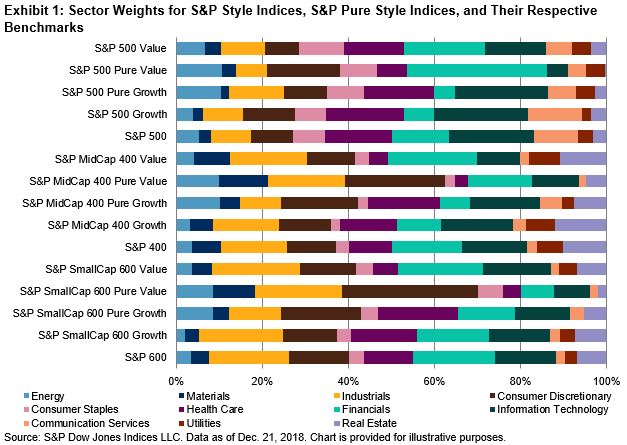

In this blog, we examine the excess returns from a sector perspective. With its higher style focus, we expect the S&P Pure Style Indices may also have more concentrated sector exposures. Therefore, we assess the performance differences between the two style series using sector grouping. In Exhibit 1, we lay out the sector weights for the two style indices compared with their benchmarks.

Across all size segments for value indices, the pure versions had higher concentration in fewer sectors compared with the style indices. One such sector is Consumer Discretionary, where the pure value had almost double the weight versus value.

Interestingly, the sector allocation for pure growth indices was less distinctive compared with growth indices, based on data as of Dec. 21, 2018. Energy was the only sector where pure growth indices had consistently more weight relative to growth for all size segments. A potential reason for this lies in the growth factors used in index construction. Although Energy did poorly in 2018 in terms of price momentum, it increased significantly in terms of earnings and sales growth (which is on a three-year basis).[1] We covered the fundamental analysis for these indices with more detail in the first blog of this series.

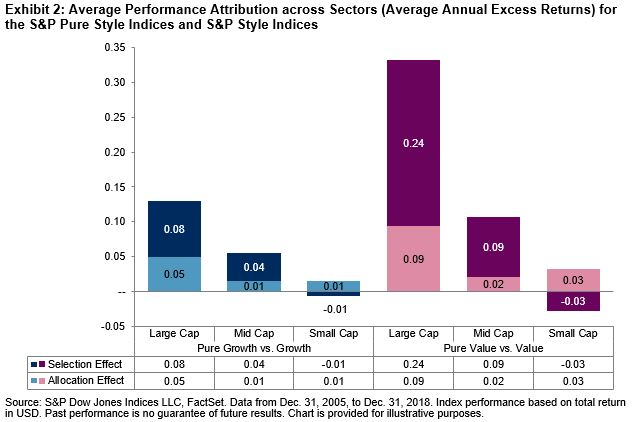

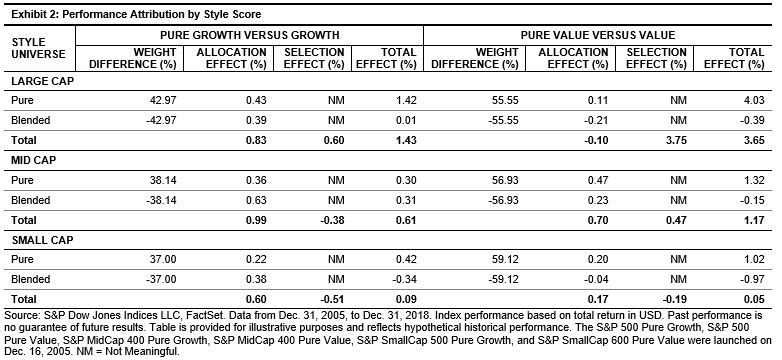

But did this higher concentration in sectors detract from performance? Using sector grouping, we computed the performance attribution on an annual basis and reported the average of the figures in Exhibit 2.

We found that stock selection played a larger role in explaining the returns than allocation differences for large- and mid-cap segments when grouped by sectors. The opposite occurred in small caps, where allocation differences among the sectors drove the excess returns. For full details and numbers by sector, please see our paper, Distinguishing Style from Pure Style.

In a following post, we will look at how these indices behave in different market and style cycles and explore implications for those characteristics.

[1] Based on the Index Earnings Report for the S&P 500, S&P MidCap 400 and S&P SmallCap 600, which can be accessed under the Additional Info tab at https://spindices.com/indices/equity/sp-500, https://spindices.com/indices/equity/sp-400, https://spindices.com/indices/equity/sp-600, respectively.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.

Source: S&P Dow Jones Indices’ “

Source: S&P Dow Jones Indices’ “