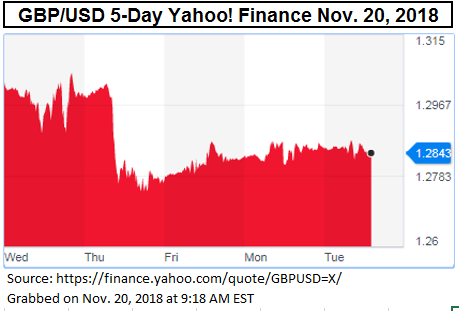

One of the main recent headlines has been the strength of the UK pound from the proposed Brexit transition. This brings into question how investors in the UK and Europe may possibly position themselves in the U.S. equity market. Notice in the past five days, the USD to GBP started from a high of 1.305 on Wed, just to drop slightly to 1.302 on Thursday before plunging to 1.275.

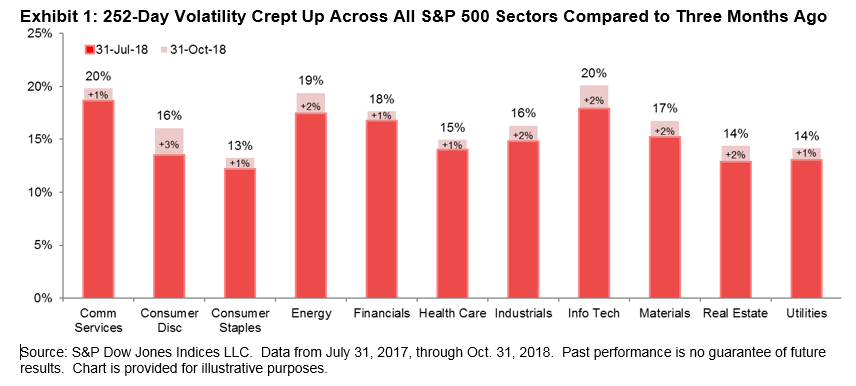

Also, while not as much as in the U.S., volatility has crept up in the UK with the S&P United Kingdom BMI (US Dollar) 30-day annualized volatility reaching 16.1% on Nov. 15, nearly doubling its level of 8.7% on Sep. 27. With the increase in volatility, especially in large caps in the S&P 500, investors may question the power of the U.S. equities to diversify a UK or European equity allocation.

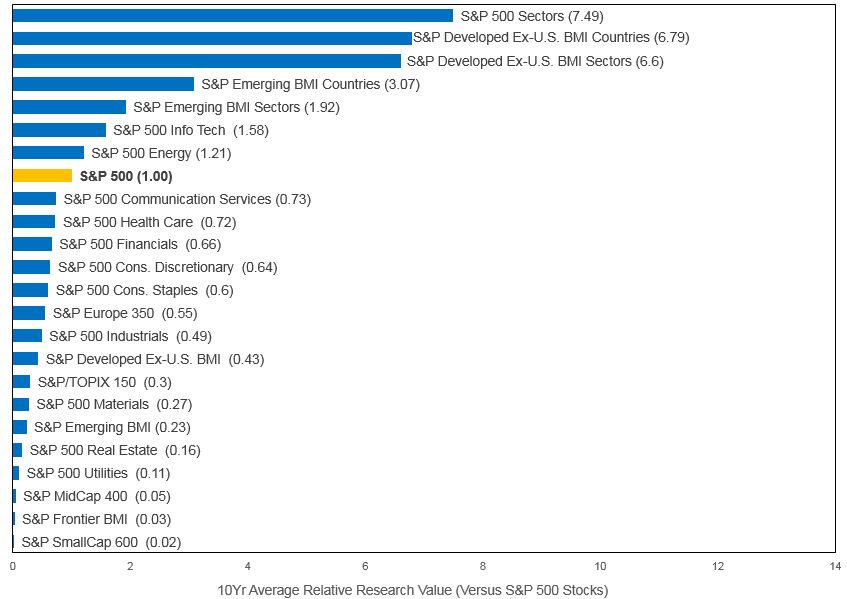

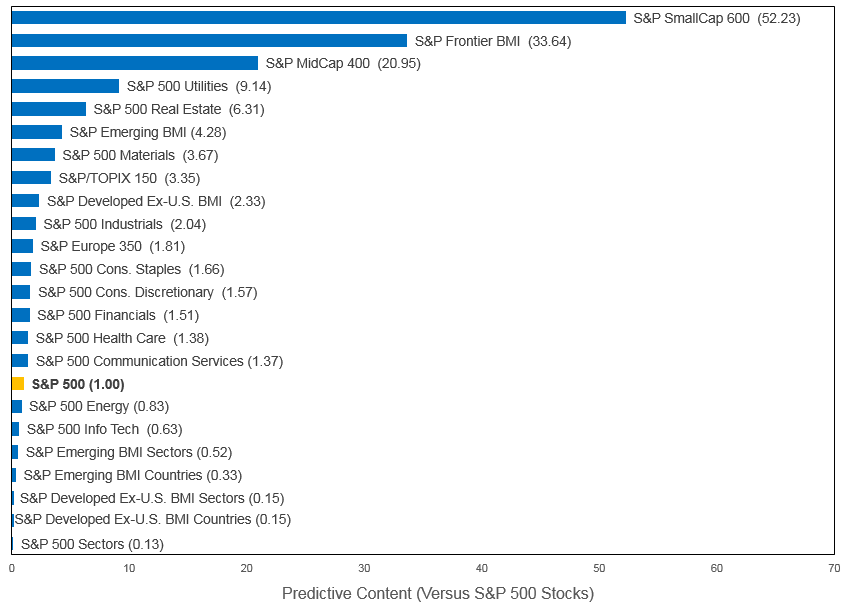

However, the longer term returns from the U.S. are significantly higher over several periods, which makes the case for excluding them difficult to prove. While most international investors use the large caps for their U.S. equity exposure, perhaps one may consider the historical benefits of mid-cap or small-cap that have been more powerful, especially now that the volatility of large caps has risen to the level seen in the S&P MidCap 400 and S&P SmallCap 600. If the long-term historical outperformance of the small-cap and mid-cap hold, then one may earn almost a 3% annualized premium over the long term – as long as there is quality like in the S&P 500, S&P MidCap 400 and S&P SmallCap 600.

The mid-caps and small-caps also have lower historical correlation with international equities. For example the correlation of the UK to U.S. large-caps is 0.81, but is just 0.67 to small-caps. This is likely not just from size but from the percentage of revenues generated domestically that differ from larger to smaller companies. The S&P SmallCap 600 generated nearly 80% of revenues from the U.S., while the S&P 500 generates just over 70%.

Not only is there more potential diversification in the traditional sense from lower correlation of smaller companies to international equities, but there is more downside protection historically from mid-caps and small-caps than from large-caps. For every 1% drop historically in the UK, the S&P 500 fell on average 58 basis points, while the S&P MidCap 400 fell on average 51 basis points and the S&P SmallCap 600 fell on average just 44 basis points.

Lastly, one may consider that whether the dollar falls or rises, large caps are not historically positioned to benefit most. If the dollar falls on average 1%, mid-caps have performed best gaining on average 3.2% versus 2.6% for large caps and 3.0% for small-caps. Meanwhile if the dollar rises 1% on average, it is small-caps that have performed best, gaining on average 95 basis points, while mid-caps gained 82 basis points on average and large-caps gained least on average with just 71 basis points. This is since the small caps have most revenue generated domestically but mid-caps have the capacity to grow business internationally when the dollar falls.

Taking into account the dollar volatility, the lower correlation, higher returns, lower downside capture ratios and now even volatility, an international investor may like to consider moving beyond large caps for their U.S. equity allocation and include mid-caps and/or small-caps.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.

Source:

Source:  Source:

Source: