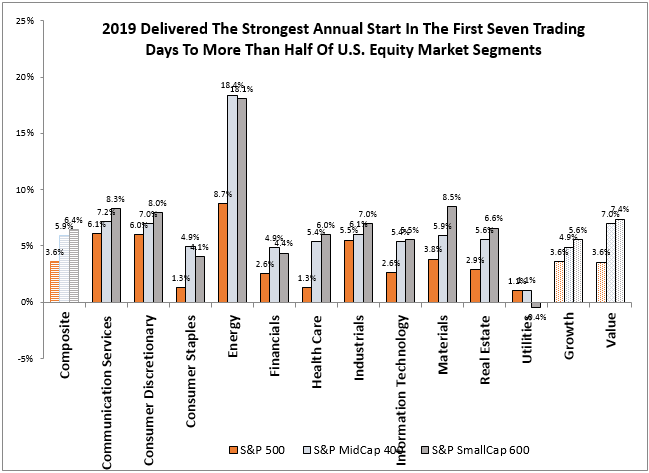

In the first seven trading days of 2019, the S&P 500 returned 3.6%, its 12th best start on record since 1928 and best since 2003. Also, the S&P MidCap 400 and S&P SmallCap 600 surpassed large caps by posting their best gains ever to start a year. Lastly, more than half the segments by sector, size and style have posted their biggest gains in history.

The S&P 500 posted five consecutively positive days, ending January 10, 2019, returning a total of 6.1%. The last time the S&P 500 returned five consecutively positive days was ending September 14, 2018, but the cumulative return was just 1.2% then. Five straight days of positive returns has happened 4% of the time since January 4, 1928, but in just 44 prior instances or 0.2% of the time, has the return been bigger than now. The last time the five day return (with all positive days) was bigger than 6.1% happened in the streak ending July 13, 2010, returning 6.5%. The last January that had a five day winning streak this big happened in January 1987 that occurred in the first five trading days of that year and returned 6.2%.

Across all the size, style and sector segments, 22 of 42 total posted their best start to any year in the first seven trading days. The S&P SmallCap 600 and S&P MidCap 400 each posted their best start in history, gaining a respective 6.4% and 5.9% with value outperforming growth. Eight of eleven small cap sectors, six of eleven mid-cap sectors, and just two of eleven large cap sectors started strongest this year. Energy and consumer discretionary each had their best start despite size.

The leading sectors may be currently influenced by the falling dollar and trade negotiations. Historically the falling dollar is best for mid-caps, since a falling dollar may help mid-caps grow internationally as they are big yet nimble enough to take advantage of new opportunities overseas. However, energy is particularly sensitive to the dollar drop since oil is priced in dollars. Though all sizes of energy performed well with oil’s recent rise, mid- and small-cap energy returned more than double its large cap counterpart, which is not surprising with rising oil as larger companies hedge more against the price volatility.

The S&P SmallCap 600 and S&P MidCap 400 respective gains of 6.4% and 5.9% to start the year outpaced large caps gain of 3.6%, which is historically typical in early bull markets. However, it may be too soon to tell whether the Fed has more influence on the stock market than other unresolved issues both domestically and abroad like trade tensions, Brexit and the partial government shutdown. Historically in a rebound, the financial sector and real estate sector performed best but this bounce is led by energy, consumer discretionary, industrials and materials, showing the move may be more focused on issues abroad – in addition to interest rate comments from the Fed. If the dollar rises more, small-caps have done historically best from their high percentage of domestic revenues, but energy might be put under pressure with the rising dollar, especially in the less hedged mid-and small caps.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.