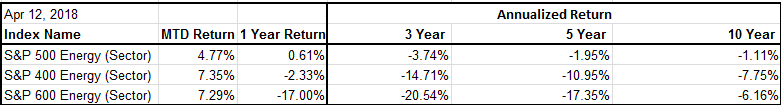

As oil prices continue to increase, the energy sector is rising but recently the mid and small cap stocks are outpacing the large caps. Thus far in April (month-to-date through April 12, 2018,) the energy sector is leading all other sectors, but the S&P 500 Energy (Sector) is up just 4.8% versus the gain of 7.4% in the S&P MidCap 400 Energy (Sector) and 7.3% in the S&P SmallCap 600 Energy (Sector).

This is an interesting turnaround from the major large cap outperformance in energy over the last 1, 3, 5 and 10 years.

Generally when looking into what drives sector performance, examining the next most granular GICS (Global Industry Classification Standard) level called industry groups is a good starting point. In the case of energy, there are no separate industry groups, but the next specific level called industries splits the sector into two parts: 1. Energy Equipment & Services, and 2. Oil, Gas & Consumable Fuels.

Immediately, the difference in performance between the two industries is apparent and can give some insight into what is driving the sector. Annualized over the last 10 years that included the both the 2008-9 oil price decline and the 2014-16 drop, the large cap oil, gas & consumables industry held up better than the energy equipment & services, losing only 40 basis points annualized versus the 3.8% annualized loss over the period. This shouldn’t be too surprising considering the energy equipment & services contains companies mainly in oil and gas drilling and equipment manufacturing, whereas the oil, gas & consumable industry includes many integrated companies, refining and marketing, and storage and transportation stocks. The long-term performance split reflects how the upstream versus mid- and downstream oil companies are sensitive to oil price declines. On the flip side, with the oil comeback, now the energy equipment & services are rebounding strong with returns more than double the oil, gas & consumable fuels in mid and small cap energy.

Overall, energy stocks may not fully capture oil price moves since companies hedge against some of the volatility, and also make other decisions for shareholder value that may not have direct influence from the oil price. Large companies are more likely to hedge against oil price moves, and again, the upswing may help upstream more since they are the ones drilling and selling the direct oil rather than buying it to transport, refine and market. According to the index data from 1995, using the S&P GSCI Crude Oil index as the oil price proxy, for every 1% rise in the price of oil, the large cap energy sector only gains about 37.5 basis points on average, while the mid- and small cap energy sectors gain 61.8 and 64.1 respective basis points. Also, the large cap energy equipment and services gains 54.5 basis points versus the gain of 34.9 basis points from large cap oil, gas and consumable fuels for every 1% rise in oil price.

However, the split between the two industries by weight is not equal but is according to market capitalization, so there may be adjustments market participants may make by deliberately tilting towards small caps or using the S&P Oil & Gas Equipment & Services Select Industry Index to get more exposure to the energy equipment & services industry. This may be especially potent alongside the S&P 500 Energy sector where the weight to this industry is relatively small at only 14% of the sector.

While these weights are only recent, the allocations between industries have held relatively constant through time in large and small caps, though in mid caps, the energy equipment & services diminished from almost 1/2 to 1/3 of the weight from the under-performance in the last 3 years. Therefore, by either using small-cap energy, or if using large-cap or mid-cap energy, to supplement with the select sector S&P Oil & Gas Equipment & Services Select Industry Index may help protect against inflation and get more upside with rising oil prices. Remember as oil prices rise, inflation is more likely and the energy sector is potentially more attractive, so it makes sense to pay attention to the more sensitive pockets in the industries of the broad sector.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.