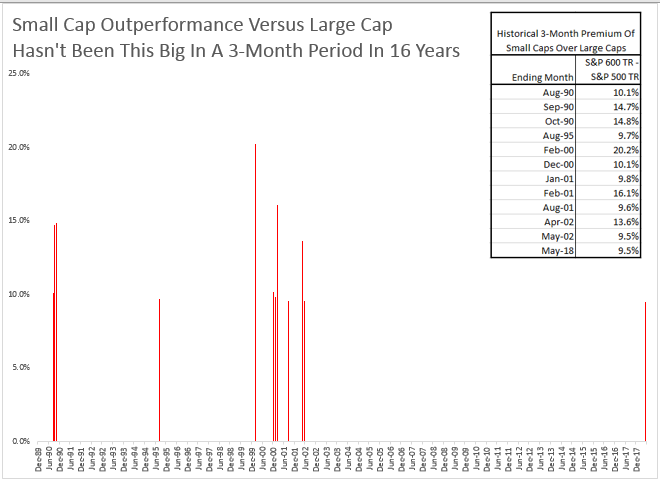

Small caps just outperformed large caps for three consecutive months for the first time since Sep. 2016. From Feb. through May, the S&P SmallCap 600 (TR) outpaced the S&P 500 (TR) by 9.5%. It is the biggest premium realized in a three month period since the three months ending in May 2002. In fact, outperformance this big has only happened in a three month period twelve times in history since Sep. 1989.

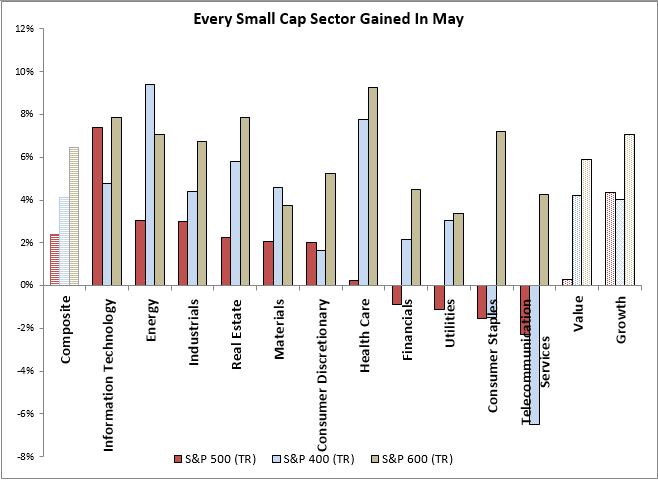

Also, in May, all eleven sectors of the S&P SmallCap 600 gained for the month. This is the first time all the small cap sectors are positive together in a month since Dec. 2016, and it is a historically quick comeback from Feb. when all the sectors were negative. This is only the 9th time in history since Jan. 1995 that the small cap sectors went from all losing to all winning in three months or less, and the last time it happened was in Oct. 2015.

The small cap rally that drove the 6.5% total return of S&P SmallCap 600 in May was led by the Health Care +9.3%, Information Technology +7.9% and Real Estate +7.9% sectors. Comparatively the S&P 500 posted a total return of 2.4% for the month, led by Information Technology +7.4%, Energy +3.0% and Industrials +3.0%. Four sectors, Telecommunication Services, Consumer Staples, Utilities and Financials lost in large caps, down a respective 2.3%, 1.5%, 1.1% and 0.9%. The S&P MidCap 400 TR gained 4.1% in May with 9 of 11 positive sectors.

In May, health care measured outperformance of small caps over large caps of 9.0%, the most of any other sector. As mentioned in this prior post, small cap health care companies have outperformed large caps for several reasons including healthy deal making, increased expectations for acquisition of smaller companies, stronger innovation from smaller companies and that smaller companies may be more immune to concerns about regulatory pressures in healthcare.

Another sector with almost just as much of a small cap premium in May is consumer staples with a premium of 8.8%. The current economic backdrop is helping the small cap consumer staples more than the large caps in the sector (Note the large cap consumer staples lost for its fourth consecutive month, down a total of 13.9% from Jan. 31, 2018. It is the 8th worst four month return in history, and worst four months since the four months ending in Feb. 2009.) Smaller consumer staple companies historically do better from GDP growth, gaining on average 5.9% per 1% of growth, as compared to the large caps that rise just 4.0%. Furthermore, rising rates help small cap consumer staples more than large caps. For every 100 basis point rate hike, small cap consumer staples rose 7.2% on average historically, whereas the same rate hike has only pushed large cap consumer staples up 4.0% on average. Lastly, the strengthening dollar may be a force that helped the small caps in consumer staples since they do more domestic business. On average per 1% rise in the U.S. dollar, the small cap consumer staples rose 1.8% versus the large caps that rose only 1.3%.

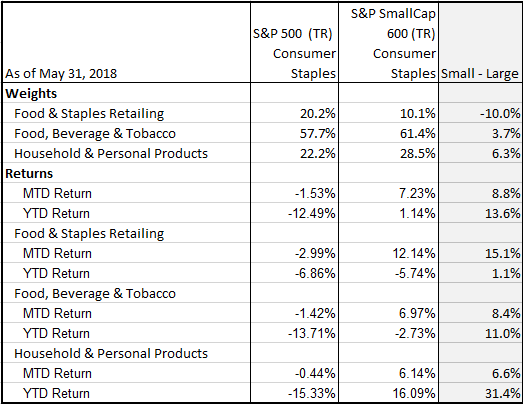

As with all sectors, it is important to drill down further into industry groups, and in some cases even into the more granular industries and sub-industries for clarity about where the performance and potential opportunities exist within a sector. In the case of consumer staples, there are three separate industry groups: 1. Food & Staples Retailing, 2. Food, Beverage & Tobacco and 3. Household & Personal Products. The Food & Staples Retailing industry group had the highest small cap premium for the month, with small caps outperforming large caps by 15.1%. However, the contribution to the returns from the Food, Beverage & Tobacco industry group were far more substantial from a weight that is about 60% of the sector. While the return spread of small over large in Food & Staples Retailing was far more than the 6.6% differential in Household & Personal Products, the contribution to return was slightly more from the Household & Personal Products due to the weight distribution.

In considering strategy, it is not just the return but knowing the underlying weights, size and the number of stocks allowing for opportunity or diversification. Note in the consumer staples sector, there are 33 stocks in the large caps and 20 stocks in the small caps, but when split by industry group, Food, Beverage and Tobacco has the majority with 21 big names and 11 small names. Interestingly, the top 10 constituents total are similarly concentrated, comprising about 70% of each index with the top holding in each near 12%. The biggest name is Altria Group Inc. and the biggest in the S&P 600 Consumer Staples is Andersons Inc. The flexibility to change prices of goods quickly is a key to performance in this market, especially if inflation might be a concern.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.