It seems generally acknowledged that no investment strategy should be expected to offer an optimal trade-off between return and risk in all periods. Yet I often hear criticism of market-cap weighting, presumably because modern portfolio theory (MPT) postulates a hypothetical market portfolio as efficient in the mean-variance sense. Financial engineers, product developers, and asset managers point to a growing range of alternatively weighted strategies designed to capture various risk premia or market anomalies. In other words, they seek to harvest greater mean-variance efficiency than cap weighting. While we all want more return per unit of risk, it is nevertheless worth remembering a few salient characteristics and benefits of cap weighting.

First off, all non-market-cap-weighted strategies aggregate into the market portfolio, which by definition is a cap-weighted portfolio. Therefore, cap-weighting is the only approach that provides a model of the market. If one seeks equity returns but has no basis upon which to develop security or factor-level return expectations, buying a model of the market avoids guesswork.

Secondly, market-cap weighting is transactionally efficient and tax efficient, requiring only minimal rebalancing to account for changes in shares outstanding. I have heard it stated that as companies become larger, there is forced buying of their shares in index funds, but that is not the case. When a company’s market cap grows, existing shareholders only need to continue holding their shares. Only net new cash flows into index-based funds (or active funds) produce buying to the extent that asset managers wish to avoid cash drag. There are also highly liquid exchange-traded derivatives that, in addition to cash market share purchases, offer efficient means of cash equitization.

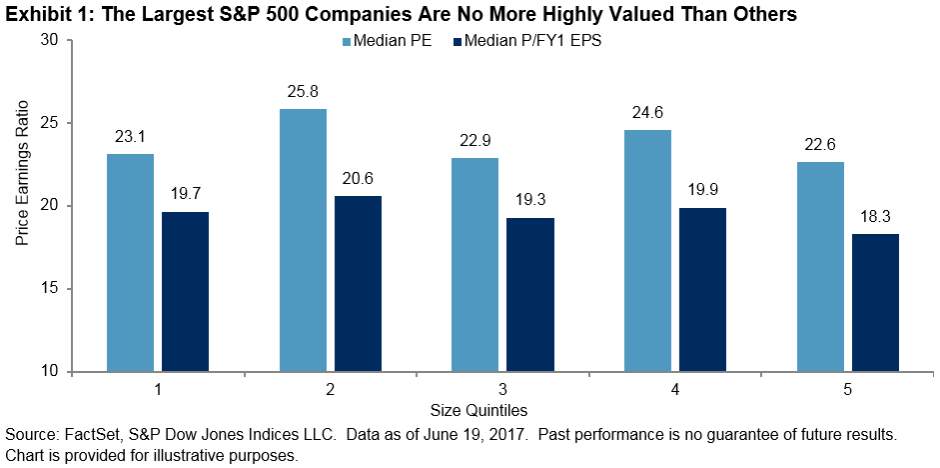

Lastly, and perhaps related to the forced buying theory above, market-cap weighting is criticized for promoting overvaluation and enabling stock price bubbles. The premise here seems to be that the largest stocks are the most expensive. There may be historical examples of such conditions, like the bubble in information technology shares in the late 1990s, but these periods are much more the exception than the rule. As of mid-June 2017, the largest companies in the S&P 500 (those making up Quintile 1 in Exhibit 1) were no more highly valued relative to past earnings—or expected future earnings—than others.

Factors such as value, momentum, and quality, as well as other alternatively weighted investment approaches, may offer enhanced mean-variance efficiency in particular periods, but it is a Herculean task to identify risk premium leadership period to period and year to year. Many investors would be better off in the long run choosing a model of the market, trying to save more, and identifying an appropriate level of overall equity exposure that considers their circumstances and risk tolerance. It’s all about blocking and tackling for a lifetime.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.