(“Excess Return” does not mean any additional return on the ETF’ s performance) is a footnote in an ETF provider’s investment objective about an ETF that tracks the S&P GSCI Crude Oil Excess Return. That disclaimer is true but never explains what excess return means in terms of additional performance. After all, excess means more, and more return is good OR is anything in excess likely to be bad?

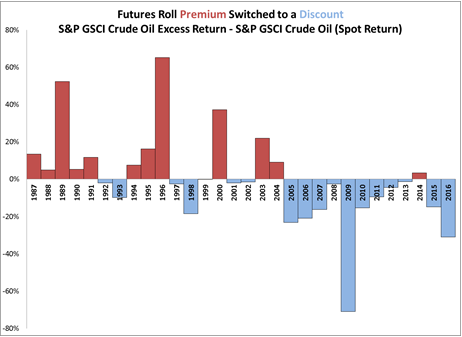

The “excess return” name describes the version of the indices that measures the change in the spot price of the futures contract plus the return from rolling the expiring futures contract into a new one. In other words, the excess return is the additional return from holding futures contracts through time rather than the spot commodity. Back in 1991, when the S&P GSCI was launched, excess return was positive. However, since 2005, the premium has mostly turned into a discount that makes holding futures contracts more expensive than the spot. The “excess return” meaning switched from more return to less return.

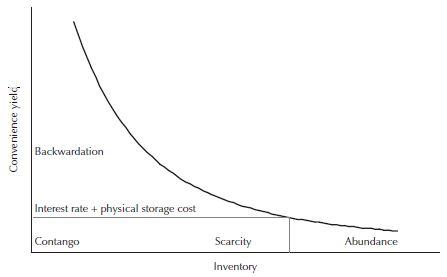

Shortages were prevalent before 1991, causing a premium on the futures contracts with nearby expiration dates. This is since processors are willing to pay extra to have immediate access to a commodity during a shortage. For example, a refiner is likely to pay a premium to have oil when there is a shortage so that its production of gas is not disrupted. The chart below shows the less inventory available, the more one will pay for the convenience of owning the commodity.

In response to a world in fear of running out of resources, producers raced to supply commodities they thought the market needed. Inventories grew into excess circa 2005 just before the global financial crisis dried up demand. The reality of an ending Chinese super-cycle in the face of an oil supply war, together with a range of unfavorable macro factors like a strong U.S. dollar, low interest rates, low inflation, and low growth plagued the last decade for commodities. This left an abundance of oil driving the excess return to be negative, the condition that still holds today.

In response to the negative excess returns, a myriad of new indices emerged to modify contract selections and rolling strategies to reduce the loss. One of the early but still popular strategies is called “enhanced”. The S&P GSCI Crude Oil Enhanced Excess Return selects whether to hold the nearby most liquid contract, or the later-dated December contracts (of the current year (Jan-Jun) or next year (Jul-Dec)) based on the amount of contango (or excess inventory leading to negative excess return) and rolls in the 1st-5th business days of every month, rather than the typical 5th-9th.

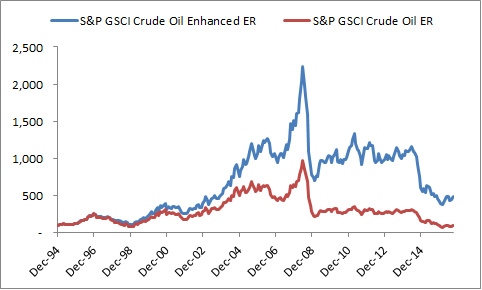

Since 1995, the enhanced modification has added 0.54% per month on average that equates to a 7.49% annualized return for the S&P GSCI Crude Oil Enhanced ER versus -0.33% annualized return for the S&P GSCI Crude Oil ER.

Just like “excess” means more, “enhanced” means better. However, just like excess return can be negative, enhanced can underperform. For the third consecutive month (as of Oct. 21, 2016,) the S&P GSCI Crude Oil Enhanced ER is underperforming the S&P GSCI Crude Oil ER, so investors are wondering why the enhanced strategy not not working.

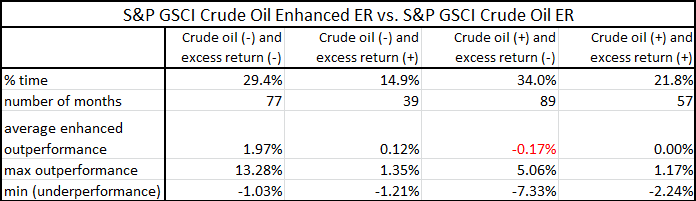

There are four conditions to evaluate how the enhanced oil strategy works. 1. Crude oil is negative and excess return is negative, 2. Crude oil is negative and excess return is positive, 3. Crude oil is positive and excess return is negative, and 4. Crude oil is positive and excess return is positive. The major outperformance of the enhanced oil happens in the case where oil is negative and the excess return is negative. This makes sense since the strategy was designed to reduce the loss from negative excess returns. There is minimal impact when excess return is positive since the enhanced index holds the front contract that is the same as in the original strategy. Some performance difference can be attributed to the different rolling days and some difference happens in months where the term structure changes mid-month before the enhanced index can move to the contract assigned for the condition. The worst scenario for the crude oil enhanced is when crude oil is positive but the excess return is still negative. This happens since as the oil price is increasing, it takes time for the excess inventory to draw down, that drives the excess return to remain negative until a shortage happens. The enhanced rules have a 0.5 contango (or negative excess return) threshold to push the contract out to a later expiration, so there are months in the transition where a smaller negative excess will force the enhanced version into the nearby most liquid contract despite some contango from the remaining abundance.

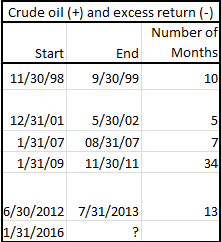

The crude oil positive and excess return negative is the condition now that is underlying the S&P GSCI Crude Oil Enhanced ER underperformance. How long might that last is the next question investors want to know. Historically, there have been five major periods of this condition lasting on average 13.8 months with the shortest period lasting 5 months and the longest lasting 34 months.

After 9 months since the bottom of oil and a persistent abundance, the tide might be turning. The excess return is the smallest negative it has been at since July 2015, and is now just under 1%. The outcome of OPEC’s effort to cut production and the ability of non-OPEC to keep supplies low will impact how long this recovery takes. The key risks are that OPEC’s cuts are too little too late – or they don’t agree on a production cut at all, and China may increase oil imports more before the price rises even higher – that will reduce demand later and possibly extend recovery time, especially if they start exporting more to turn a profit. Also, US inventories need to decline, the weather needs to get cold, China’s growth needs to pick up to help the oil market rebalance.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.