The past two months saw bouts of market volatility, which in turn is causing market participants to refocus on defensive equity strategies. Quality, together with other defensive factors such as low volatility, has a higher degree of downside protection compared with other risk factors like value or momentum. For example, during months in which the returns of the S&P 500 are negative, the quality factor has higher returns than the benchmark about 75% of the time (see Exhibit 1).

As such, we examine the long-term performance of the S&P 500 Quality Index to understand the underlying sources of the excess returns. To do so, we look at the security selection criteria of the S&P Quality Indices.

The S&P Quality Index Series uses a company’s overall quality scores for security selection. The overall quality score is composed of three fundamental ratios: balance sheet accruals ratio (BSA), return on equity (ROE), and financial leverage ratio (leverage).[1]

To understand the performance sources of the S&P 500 Quality Index, we dissect the index performance into three components: the S&P 500 Quality BSA Attribution, S&P 500 Quality Leverage Attribution, and S&P 500 Quality ROE Attribution.[2] Assuming a starting value of 100 on June 30, 1995, Exhibit 2 shows the cumulative values of the S&P 500 Quality Index and its three attribution components from June 30, 1995, to Nov. 30, 2018.

In Exhibit 2, we can observe that the BSA factor has had the highest cumulative returns among the three factors, followed by ROE and leverage. In fact, in recent periods, the performance of the BSA has surpassed that of the S&P 500 Quality Index. However, cumulative return is just one dimension in the performance evaluation of a factor. Risk, as measured by standard deviation, is another dimension worth looking into in order to better understand a strategy or a factor’s return/risk profile (see Exhibit 3).

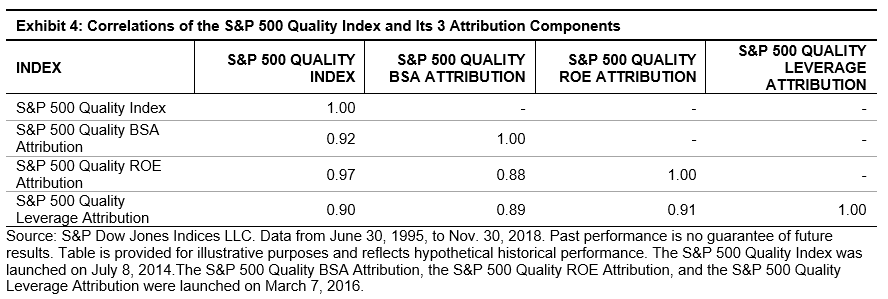

According to Exhibit 3, the integrated portfolio, as represented by the S&P 500 Quality Index, had the highest return/risk ratio when compared with the underlying component indices. This finding is not surprising given the potential diversification benefits of its subcomponents when combined in a portfolio context. The return correlations of the S&P 500 Quality Index and its components are fairly high, but not perfectly correlated (see Exhibit 4).

Market volatility has a way of making investors rethink defensive equity strategies. The S&P 500 Quality Index, with a high hit rate of 75% during down months, is a factor that has historically had a higher degree of downside protection compared with riskier factor strategies. Among its three subcomponents, the attribution analysis shows that the BSA factor has had the highest cumulative returns, followed by ROE and leverage. The potential diversification benefits of its subcomponents attributed to the integrated S&P 500 Quality Index having the highest return/risk ratio when compared with the underlying component indices.

[1] The detailed factor definition and index construction are laid out in the S&P Quality Indices Methodology.

[2] S&P 500 Quality BSA Attribution. Securities in the eligible universe are selected for index inclusion based on their accruals ratio z-score determined during the semiannual rebalancing of the S&P 500 Quality Index. The values for all securities are ranked in ascending order.

S&P 500 Quality Leverage Attribution. Securities in the eligible universe are selected for index inclusion based on their financial leverage ratio z-score determined during the semiannual rebalancing of the S&P 500 Quality Index. The values for all securities are ranked in ascending order.

S&P 500 Quality ROE Attribution. Securities in the eligible universe are selected for index inclusion based on their return-on-equity z-score determined during the semiannual rebalancing of the S&P 500 Quality Index. The values for all securities are ranked in ascending order.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.