Rising interest rates certainly has become a central investment theme going into 2017. The 10-Year Treasury yield closed at 2.48% on Jan. 27, 2017, representing an increase of nearly 103 bps from six months ago. Research has shown that equities tend to perform better following a rate hike, if inflation levels are moderate. However, return expectations on small-cap securities are mixed, as conventional wisdom dictates that small-cap securities require more capital, and therefore higher borrowing costs, for growth. It is therefore important to examine the potential performance behavior of small-cap indices in a rising rate environment.

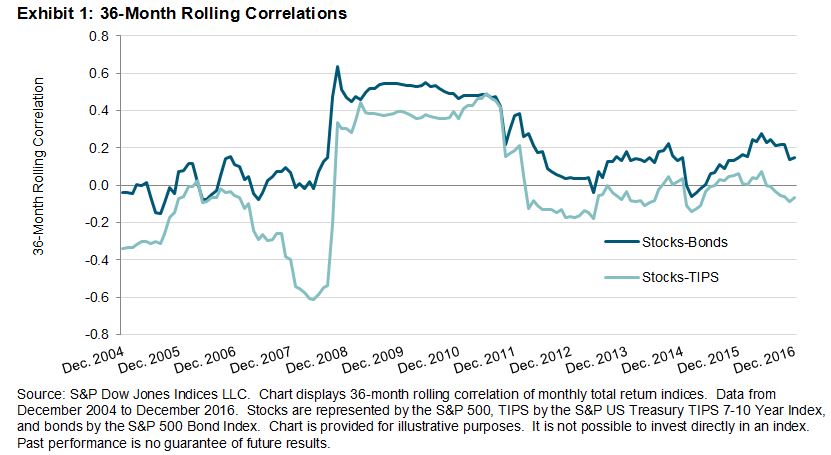

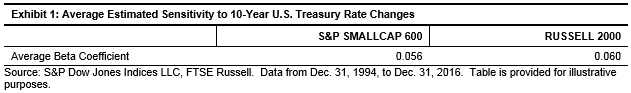

To understand the sensitivity of small-cap securities to changes in interest rates, we performed a linear regression using the monthly returns of two headline small-cap indices, the S&P SmallCap 600 and the Russell 2000, against monthly changes in the 10-Year U.S. Treasury rates. The regression equation is estimated on a rolling 36-month basis, and the average estimated beta coefficients for the two indices are shown in Exhibit 1.1

We can see that, on average, both small-cap indices have positive exposure to rate increases. In particular, the Russell 2000 exhibited slightly higher positive sensitivity to changes in rates. For every 1% positive change in 10-Year yield, the returns of S&P SmallCap 600 increase by 5.6% on average, whereas the returns of Russell 2000 increase by 6%. However, the difference in coefficients (sensitivities) of the two indices is not statistically significant at the 95% confidence level.

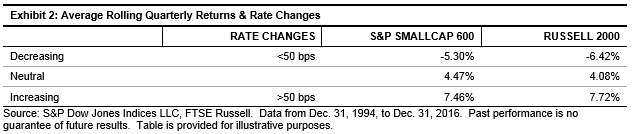

Against that backdrop, we used observable returns of the two indices and interest rate changes to analyze further. We divided the test period into three interest rate regimes—decreasing, neutral, and increasing—based on rolling quarterly changes in 10-Year U.S. Treasury yields computed on a monthly basis, and we compared the average performance of the two small-cap indices during those periods (see Exhibit 2).

The data shows that during those periods in which the 10-Year U.S. Treasury yields rose by more 50 bps, both small-cap indices delivered returns north of 7% on average. Similarly, during those periods in which 10-Year yields remained neutral or rose less than 50 bps, both indices still delivered positive returns of 4% or more. Therefore, we can observe that neutral or rising rate environments can favor smaller-cap names. Conversely, during those periods in which yields decline by more than 50 bps, both small-cap indices posted negative returns, with the Russell 2000 losing more than the S&P SmallCap 600. The finding is not surprising, given that the Russell 2000 historically has higher sensitivity to rate changes than the S&P SmallCap 600.

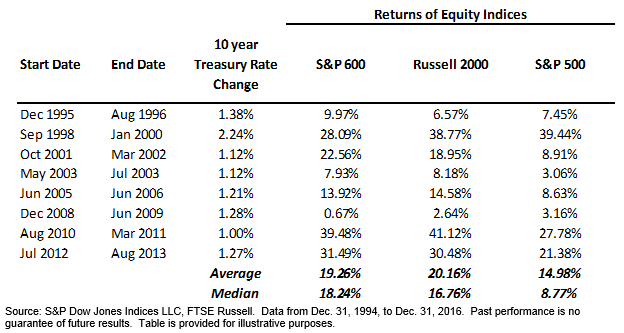

Lastly, we went back and examined periods over the past 22 years2 during which the 10-Year U.S. Treasury yields rose meaningfully, defined as rate increases of 100 bps or more from trough to peak, and we computed the corresponding cumulative returns of the two small-cap indices as well as the S&P 500 (see Exhibit 3). The data supports that equities in both large-and small-cap segments stand to gain in rising rate environments. The data, however, refutes conventional wisdom that small-cap securities are disadvantaged by rate hikes. It is possible that there are macroeconomic and fundamental factors, such as economic growth and valuations that are driving the performance of small-cap names during periods of rising rates. We intend to explore this deeper in a follow up blog post.

Based on observable realized returns and yield changes, our analysis shows that small-cap securities outperform on an absolute basis as well as on a relative basis when compared to their large-cap counterparts.

Exhibit 3: Period Analysis of 10 Year Rate Changes and Performance of Broad Market Equity Indices

1 The equation is estimated as follows: ![]()

2 Based on the earliest available data for the two small-cap indices.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.