Today in the Wall Street Journal, there is an article, “Airlines Retreat on Fuel Hedging“, that highlights the losses airline companies suffered by hedging against oil and gas rises. However, the article also points out that not all airlines hedged, including American Airlines Group (NASDAQ: AAL), who enjoyed the benefit of cheaper fuel. Scott Kirby, president of AAL, was quoted, “hedging is just a rigged game that enriches Wall Street.”

Kudos to him and his shareholders for betting in the right direction. Not every commercial consumer (airline) made that choice, but the important point is that hedging against an oil price rise is a choice about managing risk. Hedging price risk to keep a company in business is not a Wall Street game, but it is possible Kirby was referring to Paul Cootner’s research from MIT in the 1960’s that explains commercial hedging as a highly specialized form of speculation.

In a letter to the FT, Hilary Till points out the futures markets exists to help companies specialize in risk taking by allowing them to use the basis risk, the difference between the spot and futures prices, to manage risk. This is helpful since the basis risk is more predictable than the commodity prices themselves. In the same article, Till points out Holbrook Working’s research from Stanford in the 1950’s showing that it is not necessarily precise daily correlation that matters for choosing a proxy hedge, but whether the proxy hedge provides a business with protection during a dramatic price move that could bankrupt a company.

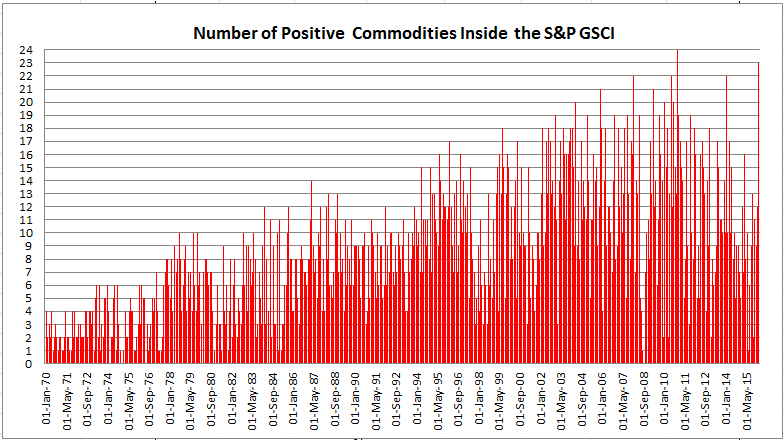

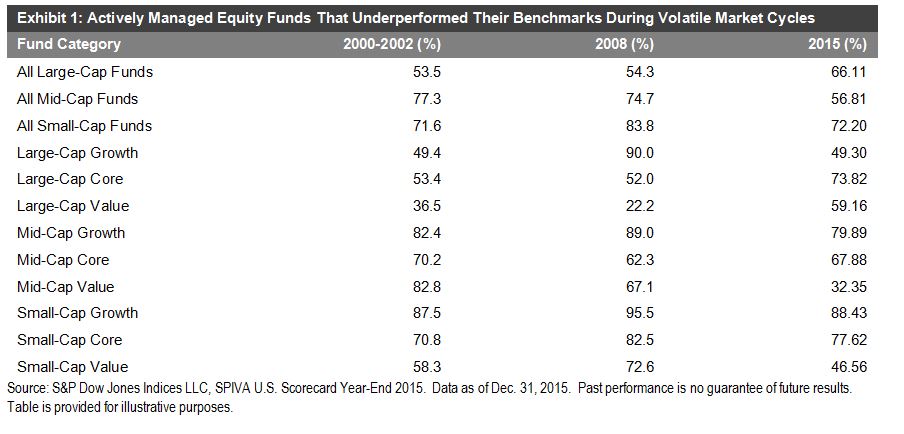

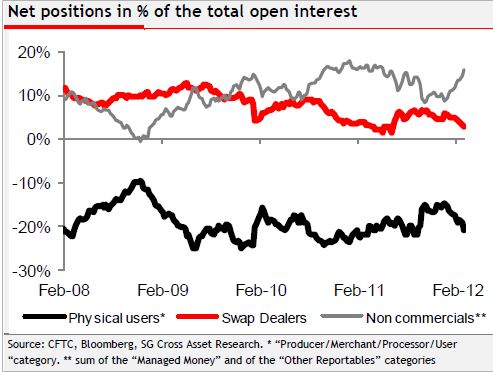

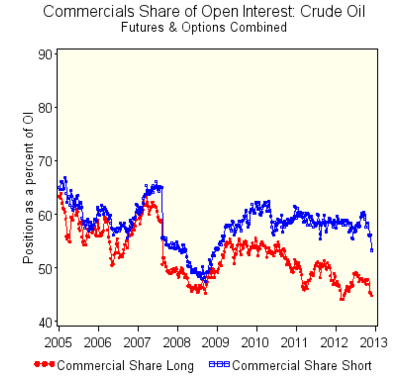

However, not all companies are similarly vulnerable to bankruptcy from commodity price moves. The producers need protection against price drops more than commercial consumers need protection against price increases. So, the producers go short to protect against price drops and the consumers go long to protect against price increases, and the result is naturally more commercial shorts than longs.

This also true specifically in oil where there has been consistently more commercial short hedging than commercial long hedging.

The reason this is the case is supported by two economic theories: 1. Hicks’ theory of congenital weakness that argues it is easier for consumers to choose alternatives so they are less vulnerable to price increases than producers are to price drops, and 2. Keynes’ theory of “normal backwardation” that argues producers sell commodities in advance at a discount which causes downward price pressure, which converges to the spot at the time of delivery.

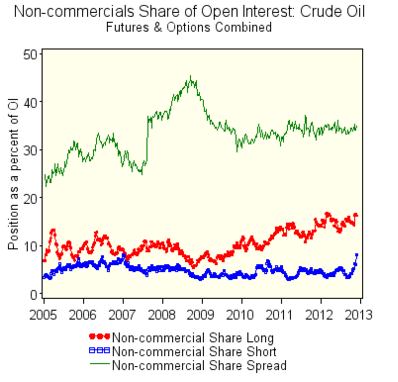

In the futures market, this gap needs to be filled between producers and commercial consumers that are hedging, opening the door for long commodity investors to earn a return called the insurance risk premium. This is illustrated by the bigger share of non-commercial longs than shorts.

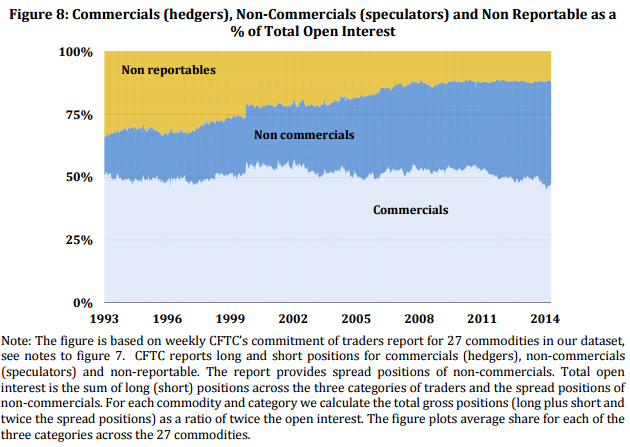

This relationship is time tested and has remained stable as examined by Bhardwaj, Gorton and Rouwenhorst. They conclude although open interest has more than doubled for the average commodity since 2004, the composition of the open interest has remained remarkably stable.

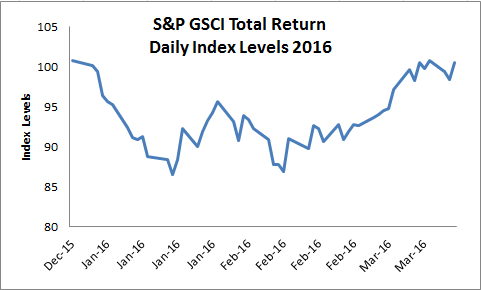

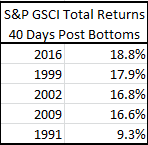

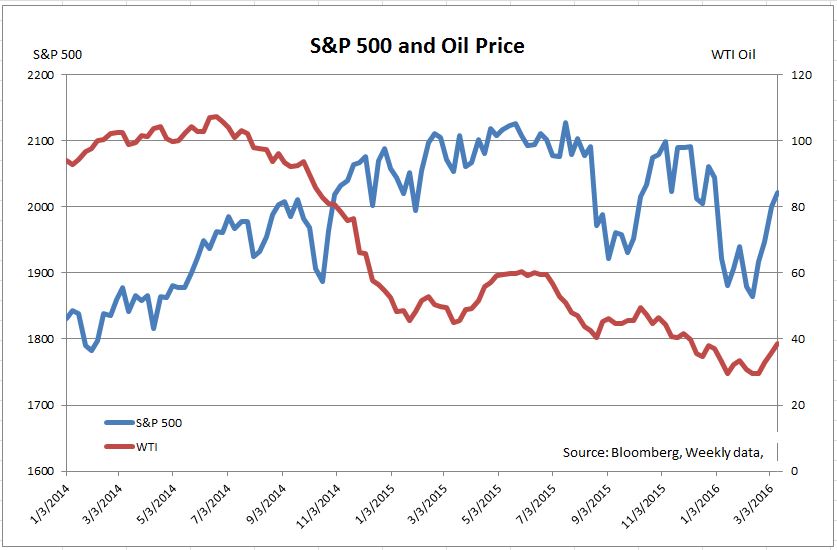

Oil index investors that use long futures should be excited if all of the above holds true and airlines really are retreating on their hedging. The implication is that there may be a bigger risk premium to be earned as the net shorts grow (from the absence of airline long hedging.) The oil producers still hold more risk than commercial consumers and will likely pay investors to offset that risk. The timing may be perfect too with the signals that show oil may have bottomed. You can read about these two signals here and here.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.