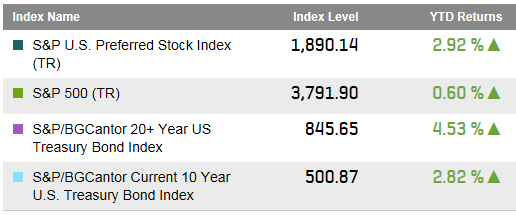

In this prolonged low interest rate environment, the S&P U.S. Preferred Stock Index has performed well, returning 2.92% year-to-date. Meanwhile, the S&P 500 (TR) is up a modest 0.6% and long term bonds tracked in the S&P/BGCantor 20+ Year U.S. Treasury Bond Index are up 4.53% in total return. So far, the preferred stock market with characteristics of both equities and bonds has performed as expected – somewhere in the middle of the performance of stocks and long term bonds.

Select Indices: Year to Date Performance (March 27, 2015):

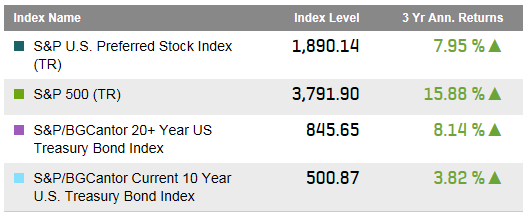

Over a three year period, the annualized returns of the U.S. preferred market have been more bond like than equity like. The S&P U.S. Preferred Stock Index had a three year annualized return of 7.95% while long U.S. Treasury bonds have returned 8.14%. Meanwhile, the three year annualized return of the S&P 500 has been well over 15%.

Select Indices: Three Year Performance (March 27, 2015):

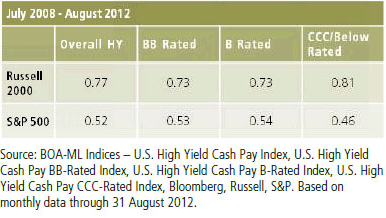

While it is easy to relate the performance of preferred stock and long term bonds to interest rate changes, the two asset classes have shown a low correlation to each other over the last three years. Actually, the S&P U.S. Preferred Stock Index has had a higher correlation to the S&P 500 than it did to long term to bonds. There is a danger in just looking at the last three years of course as interest rates have been held low during the period.

Three Year Correlations:

Will a rising interest rate environment bring the same pain to preferred stocks as it might to long term bonds? The short term history illustrates that the combined equity and bond like characteristics of preferred stock both play a role in actual performance. Like all things still to come, we will just have to wait and see how the markets unfold.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.