With all of the monetary policy including the unprecedented quantitative easing, the impacts have been different than expected. Assets became hyper correlated, the dollar didn’t drop relative to other currencies and inflation never showed up.

Recently, I had the privilege to sit down with Bluford Putnam, Managing Director and Chief Economist, of our partner, CME Group, to discuss why inflation is likely to appear this year.

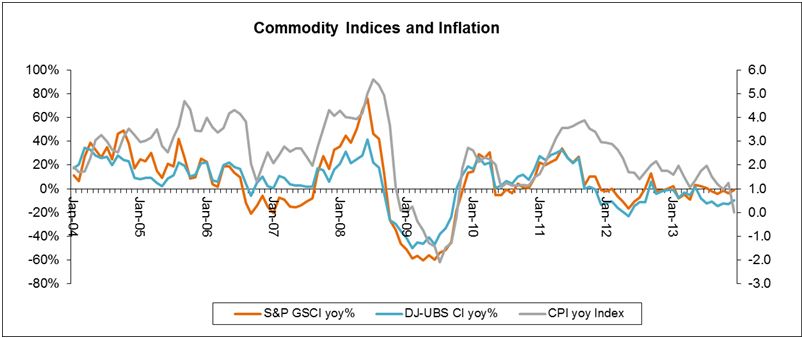

Historically, there has been a high correlation between year-over-year changes of the Consumer Price Index or CPI and commodity indices. This is since they contain many of the same components like food and energy, and the commodity indices reflect our changing expectation of future prices through the futures contracts. Also, because food and energy are major components of the CPI and are among the most volatile of inflation, they are key drivers of the indices. Over the past 10 years, the S&P GSCI has had a correlation of 0.74 to CPI and DJ-UBS has had a correlation of 0.64, where more energy has provided a higher correlation.

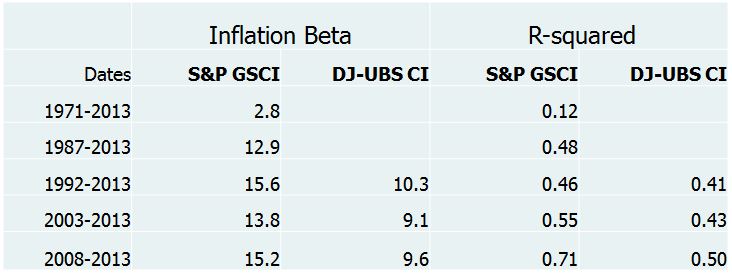

Further since food and energy typically represent a higher percentage of commodity indices than of the CPI, one dollar of investment in a commodity index will provide a basis for more than one dollar’s worth of inflation protection. In this chart, the inflation beta can be interpreted as a 1% increase in inflation results in 10.3% increase in return of the DJ-UBS during the period from 1992 through 2013. Notice the S&P GSCI has had the highest inflation beta that is likely due to its world production weighting scheme that yields a higher energy weight.

Inflation beta data are measured by CPI-U as listed on the website: ftp://ftp.bls.gov/pub/special.requests/cpi/cpiai.txt

R-squared signifies the percentage that inflation explains of the variability in commodity index returns

Inflation beta can be interpreted as: (using DJ-UBS CI 1992-2013 as an example) A 1% increase in inflation results in 10.2% increase in return of the DJ-UBS CI during the period from 1992–2013

Time periods shown reflect first full year of returns for the S&P GSCI (1971), first year crude oil was included in the S&P GSCI (1987), first full year of returns for the DJ-UBS CI (1992), 2003 a and 2008 are 5-years and 10-years.

If we look at the super accommodative monetary policy including zero interest rates and quantitative easing, it really hasn’t worked at all. The U.S. economy has been chugging along at about 2% GDP and we really haven’t seen any signs of inflation, just about 1% core. It is because of the kind of recession we’ve had that requires consumers, corporations, and governments to shrink or delever since they took too much debt. During the deleveraging process the interest rates don’t matter much – or like John Maynard Keynes said, “it’s like pushing on a string.”

Now that the deleveraging seems to be ending, the US economy has come back nicely, despite the four years it took. Consumers are borrowing again, though at more appropriate levels for their incomes, corporation have tremendous amounts of cash and are fine, and state and local governments which took a longer time to balance have stopped cutting jobs.

So, the right policy at the Fed should start working about now given inflation should be kicking in this year. Generally it takes about 18-24 months for inflation to start after the clock starts ticking, which Blu says happened around Dec 2012. However, if there is no FX feedback (and there is none now, since the USD is doing OK), the time lag might take longer or the inflation pressure might be little more muted than otherwise.

How will the Fed respond? Not clear, but if you accept the Fed’s guidance, they want to be “behind” the inflation curve and let it get started. What this means is that given their dual mandate of encouraging full employment and maintaining price stability, which is defined by them as 2% core inflation rate (that is minus food and energy), the Fed is likely to wait until inflation hits at least 2.5% until they act.

Although, it is not just about when the data gets there. The Fed needs to feel like market expectations are rising and at that point they will probably start raising fed funds rates from its near zero level at slow increments of about 25 basis points per quarter. According to Blu, they may do this until they get to about near or even 1% above the inflation rate.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.