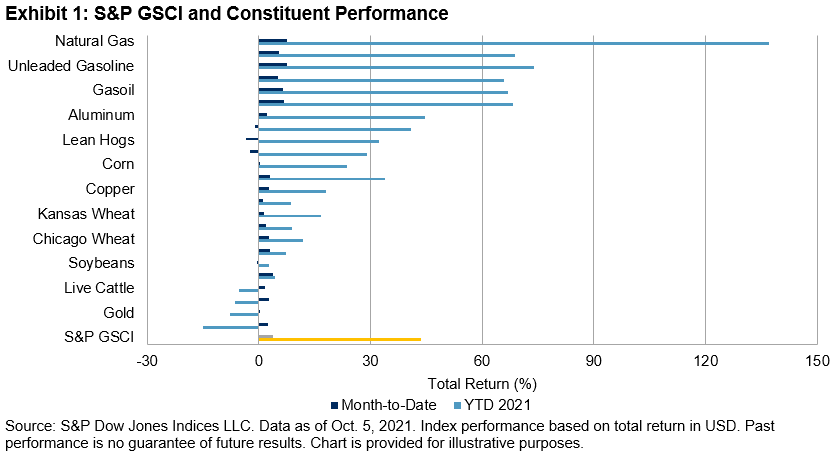

The broad-based S&P GSCI started Q4 2021 off with a bang; as of October 5 it was up 3.9% for the month and 44% YTD. The spot version of the index has reached its highest level since October 2014. Natural gas and the petroleum complex have continued their dominance of the commodity charts, filling out the top six spots among S&P GSCI constituent performances for the month. However, they all pale in comparison to U.K. and European natural gas prices, which currently sit outside the S&P GSCI single commodity series. The S&P GSCI Natural Gas, which seeks to track the performance of U.S. natural gas prices, was up 137% YTD, while benchmark U.K. natural gas prices have more than quadrupled since the beginning of June, and Dutch gas prices have risen nine-fold since the beginning of the year.

Record natural gas and electricity prices in Europe, record coal prices in China, multi-year highs in natural gas prices in the U.S., and Brent crude prices tipping USD 82/barrel are all manifestations of a global energy shortage that has come into sharp focus over recent weeks. Supply chains are stretched, in some cases broken, and energy stockpiles are abnormally low. Unusual weather has worsened the energy supply crunch, while ambitious climate plans and a growing reliance on renewable energy sources have further complicated the situation. However, energy crises are not a new phenomenon. The challenge this time around is that the global economy is recovering more quickly than expected from a once-in-a-generation economic shock while most countries are simultaneously ramping up their commitment to the energy transition and a net-zero carbon future.

Arguably, the market is doing its job; prices and volatility have spiked in an attempt to destroy sufficient demand to protect depleted inventories. European gas and electricity prices are now signaling the need for urgent factory closures in order to reduce gas consumption. For manufacturers, shutdowns have the effect of cutting energy costs, but they can also drive up the price of their products, which in turn may see inflation worries bleed from energy to other sectors of the economy.

European importers have been locked in competition with Asian buyers to attract extra liquefied natural gas cargoes, while pipeline deliveries from Russia have so far failed to respond to higher prices. China is facing an electricity squeeze of its own from a shortage of coal supplies, tougher carbon emissions standards, and strong post-pandemic demand from manufacturers and heavy industry, which have triggered widespread curbs on usage.

Physical commodities markets are prone to exaggerated price moves in both directions, and the high prices and associated levels of extreme volatility across the energy complex reflect an acute shortage of the raw materials needed to produce the energy that powers every aspect of the global economy. How long the situation takes to revert, or at least stabilize, remains to be seen, but this is yet another example of the importance of appreciating the role of commodities in the broad financial ecosystem, even for those market participants who have no intention of trading European natural gas.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.