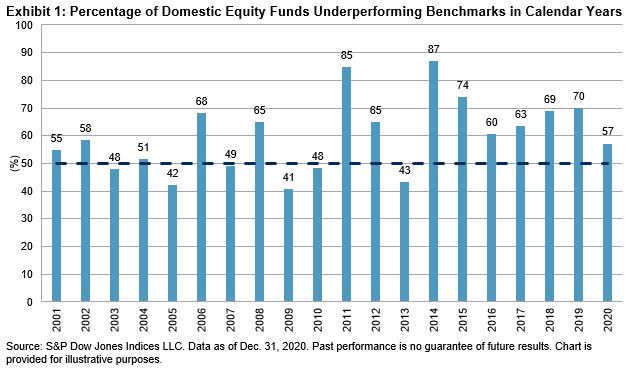

In a year that brought a pandemic, volatility, and policy stimulus, asset prices rose nearly across the board. However, positive absolute returns did not necessarily translate into success for active managers relative to their benchmarks. According to the SPIVA® U.S. Year-End 2020 Scorecard, most active fund managers in the U.S. underperformed their benchmarks over the past year. Among actively managed domestic equity funds, 57% lagged the S&P Composite 1500® in 2020, marking the seventh consecutive year in which a majority of U.S. active equity managers underperformed.

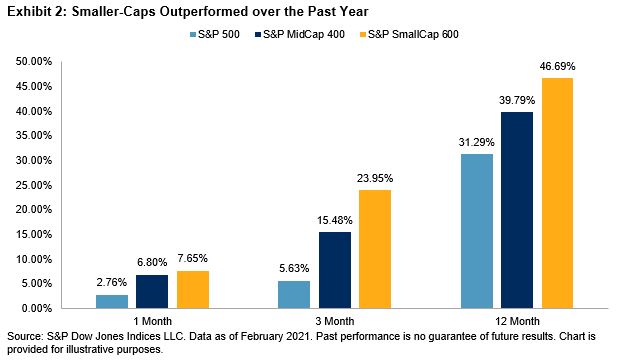

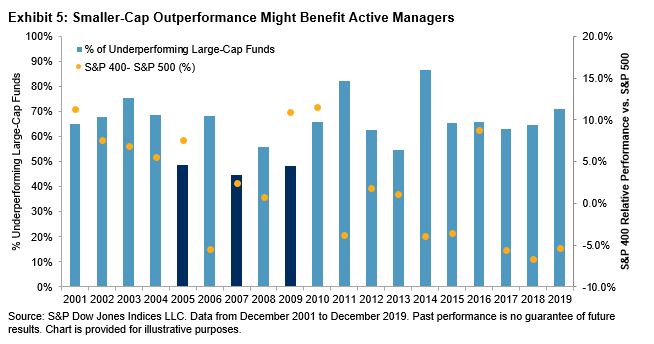

For the 11th consecutive one-year period, the majority (60%) of large-cap funds underperformed the S&P 500®. Mid-cap (51%) and small-cap (46%) funds did somewhat better relative to the S&P MidCap 400® and S&P SmallCap 600®, respectively. As we observed in our 2020 mid-year report, the performance divergence among different categories diminished as the time horizon lengthened. Over the past 20 years, more than 88% of U.S. equity funds failed to beat their benchmarks across all three market capitalization segments.

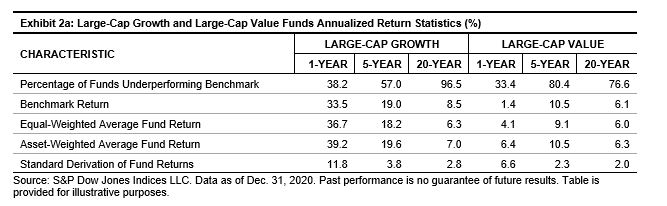

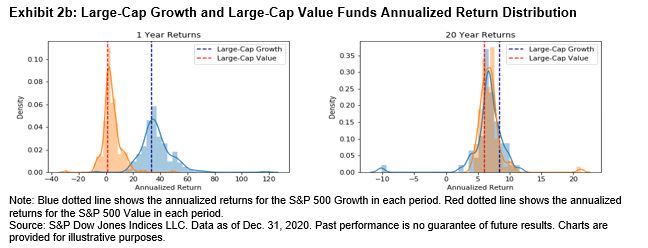

Growth funds dominated their value peers in 2020. As shown in Exhibit 2a and 2b, the equally weighted average return of all large-cap growth managers was 36.7%, approximately nine times the equally weighted average return generated by all large-cap value managers. However, the advantage of growth funds narrowed over time; there was little difference across the 20-year horizon. More importantly, longer term results showed little difference in funds’ performance relative to their benchmarks. Most funds in both categories underperformed in all periods longer than five years.

The data from the SPIVA U.S. Year-End 2020 Scorecard show a continued winning streak for passive investment. Even the few short-term active bright spots tended to lag their benchmarks over the long term. Across all capitalizations and investment styles, the most probable path for short-term outperformance is to fall short of benchmark returns eventually.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.