In the past five years, capital markets in India have witnessed bull and bear phases. The bulls accounted for most of the five-year period; however, Q1 2020 completely changed this landscape. Due to the COVID-19 outbreak, capital markets have taken a beating both globally and locally in India.

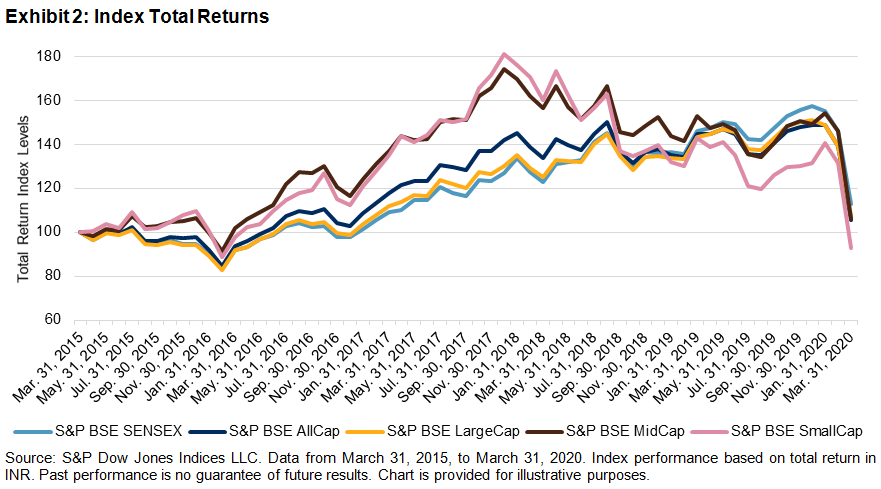

Exhibit 1 and 2 showcase the five-year returns for India’s leading size indices.

From Exhibits 1 and 2, we can see that the returns were promising for large-, mid-, and small-cap segments through December 2019; however, the scenario completely changed in Q1 2020. The returns of the large-cap segment were better than the small- and mid-cap segments across the five-year period. The S&P BSE SENSEX, which comprises the 30 largest and most liquid BSE-listed companies in India, outperformed all size indices.

Exhibits 3 and 4 showcase returns for the 11 leading sector indices in India in the past five years.

From Exhibits 3 and 4, we can see that the S&P BSE Energy and S&P BSE Fast Moving Consumer Goods posted promising returns, while the S&P BSE Healthcare, S&P BSE Telecom, and S&P BSE Industrials posted negative returns for the five-year period. All the sectors had negative returns in the Q1 2020.

To summarize, we can say that the bulls had their way during most of the five-year period across all sizes and most sectors through December 2019; however, due to the COVID-19 outbreak, things went south at Dalal street as markets tumbled across all sizes and all sectors during Q1 2020, especially during March.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.