On February 19th, the S&P 500® closed at an all-time high of 3386; last night, exactly one month later it closed at 2409, a 29% decline from the high. Let’s take a moment to reflect on what’s happened over the last month.

We should first start by putting the decline into historical context. The peak-to-trough decline in the Dow Jones Industrial Average was 33%, comparable to its slide during the bursting of the Tech bubble from 2000 to 2001. We are still off from the 54% decline in the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, and would need an even steeper drop to put this recent crisis on par with the Great Depression’s 89% market decline. The unusual aspect of the current selloff has been its speed; the previous declines happened over multiple months and years; this recent drop happened in less than a month, with some days of trading echoing the extraordinary events of 1987.

Broadly, global equities have plummeted across the board. Almost every major market is down more than 20% over the period. China, which didn’t have quite the same run-up in early 2020 due to the coronavirus’ early spread there, offers a rare exception.

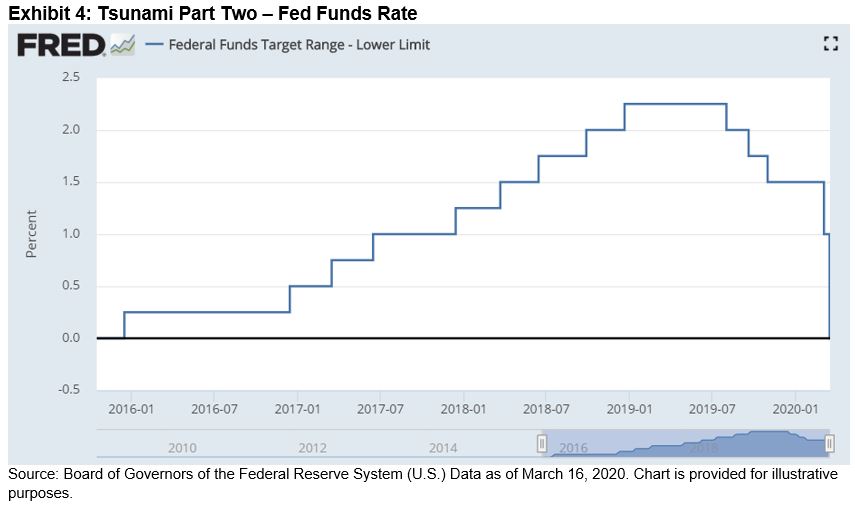

The S&P Global BMI is down 31% over the last month, wiping $19T off the market cap. Central banks and governments have stepped in to help soften the blow, announcing both monetary (interest rate cuts, QE) and fiscal (bailouts, cash to citizens) measures. While the ink is not yet dry, there have been a number of major commitments from central banks and governments, adding up to around $7.6T in total stimulus globally (and more to come). Here’s our estimate of the current extent of the so-far announced measures, in comparison to the capitalizations lost by the Global BMI’s countries.

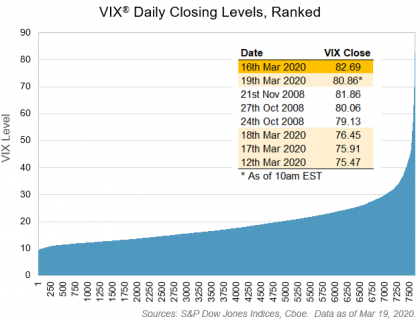

VIX® spiked to unprecedented levels. In a history that stretches back over 7,500 trading days to January 1990, five of the eight highest closing levels for VIX occurred during the recent panic. Only the peaks in volatility that occurred during the 2008 financial crisis saw anything similar. The chart below comes from my colleague Tim Edwards’ most recent blog, in which he explains that, with VIX near 80, 5% up or down is the “new normal” for the S&P 500.

It wasn’t only volatility in equity markets that shocked us, however; volatility measures spiked across nearly all asset classes, particularly oil. After Saudi Arabia’s decision to flood the market with cheap oil following a disagreement with Russia on production cuts, the price of oil plummeted, pulling the energy sector down sharply with it. We saw all time-highs in several of the volatility indicators supported by S&P DJI; here are their current levels, versus their levels one month ago, and their highest close in the interim.

Interest rates have also been extremely volatile. At one point, the U.S. 10Y Treasury yield dropped as low as 0.32% but has since rebounded to 1.04%. While it may not sound like much, those are major moves for a developed market sovereign, particularly when you consider that yields jumped back up while equity markets dropped sharply. Today the yield curve looks very different from one month ago, though it does now more closely resemble an actual curve.

What will be perhaps most interesting will be to see how active equity managers navigated the crisis. According to recent dispersion readings, the opportunity to outperform the market has been as high as its been in a long while, which means that it’s showtime for active managers.

Regardless of where the market goes from here, or if active managers have indeed navigated the choppy seas, the last month will likely be one we’d all like to forget.

For more market commentary and perspective, register at www.bit.ly/spdjidd to sign up for our daily dashboard.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.