The market highs of February 2020 already seem like a strange, distant past, in which people socialized, worked in offices, and were blissfully unappreciative of their abundant supply of toilet paper.

Life has changed. With that change, the S&P Europe 350® lost a third of its market capitalization in just a month. The market may have subsequently ticked up, but with volatility still high, it may be premature to call the bottom.

In times of market panic, it is not uncommon for defensive equity factor strategies to correlate with the market. They are, after all, still equity indices. However, the S&P DJI Risk Control Indices, which use realized market volatility to allocate systematically between an equity index and cash, were better able to cushion the crash.

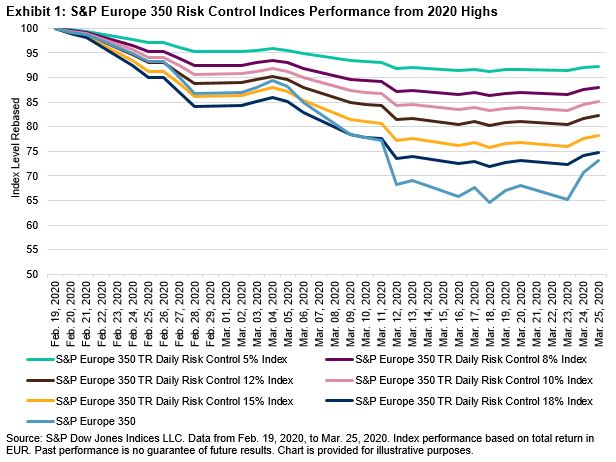

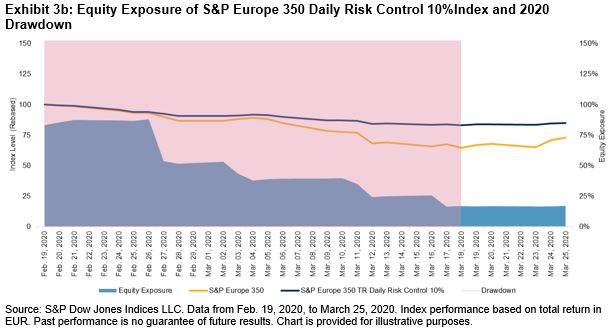

Exhibit 1 shows several risk control indices based on the S&P Europe 350. Each index targets a specific level of annual volatility (e.g., 5%, 8%, 10%, 12%, 15%, or 18%) by reducing its equity allocation when volatility is higher than this target and increasing it when it is lower. Recently, in keeping with current advice, they stayed calm and carried on (from home).

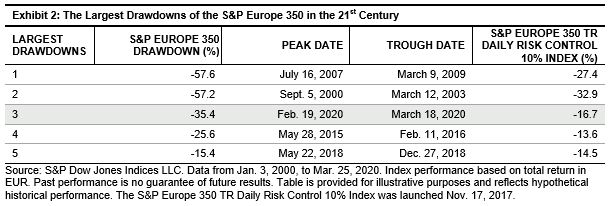

The S&P DJI Risk Control Indices are designed to hold a higher allocation to cash during periods of heightened volatility, and the recent outperformance is typical of the historical record during drawdowns for the benchmark [see Exhibit 2].

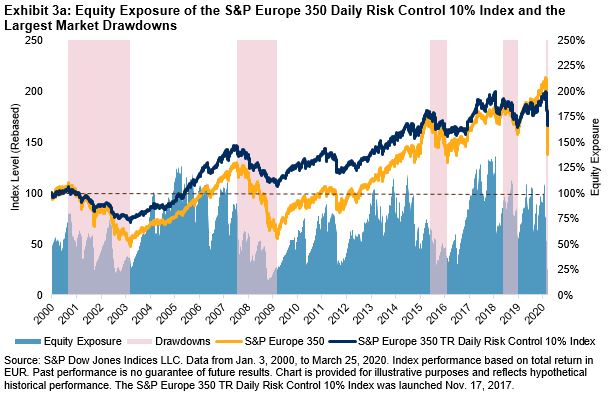

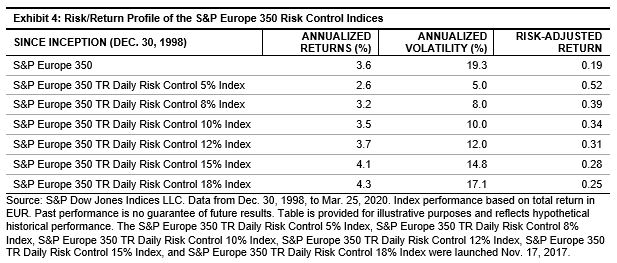

Additionally, when volatility is below target, the S&P DJI Risk Control Indices can allocate more than 100% to equities [see Exhibit 3a], so that the indices can occasionally participate more fully in market gains. This combination of drawdown protection and market participation has historically led to better performance for a given level of risk than the S&P Europe 350 over the long term [see Exhibit 4].

The S&P DJI Risk Control Indices provide an alternative, long-term solution that requires no subjective input or activity from the investor. If volatility stays high and markets continue to fall, risk control indices will continue to outperform. Should markets begin their recovery and volatility decline, risk control indices will eventually reallocate back to equities. Additionally, the target volatility mechanism will be there, ready to react again in the future.

Maybe a hands-off approach is what many of us should be looking for after all.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.