With 2019 coming to a close, market participants may use the time to evaluate portfolio performance and to assess what changes (if any) they would like to make based on return expectations and the market outlook. While the future is uncertain – hindsight really will be 2020 when it comes to evaluating next year’s returns – 2019’s market movements can provide context for where we are and where we may be headed.

2019 has been positive for U.S. equities

In contrast to the gloomy market outlooks to start the year, 2019 has been almost entirely positive for U.S. equities. The S&P 500 has posted 26 all-time high closing price levels and currently boasts a 27.4% year-to-date total return, while the S&P MidCap 400 (+22.89%) and the S&P SmallCap 600 (+19.90%) have also gained. More broadly, 42 of the 45 style and sector indices based on the S&P 500, S&P 400, and S&P 600 have risen so far in 2019: smaller energy companies and small-cap communication services stand as the exceptions.

The Fed, trade tensions, and earnings have driven sentiment so far this year

Despite the broad-based gains in U.S. equities, there have been a few bumps along the way as expectations over future Fed policy, U.S.-China trade tensions, and corporate earnings have taken it in turns to drive sentiment.

For example, better-than-expected corporate earnings, easing trade tensions, and signs of economic growth initially helped the S&P 500 to its best total return through the end of April since 1987, up 18.3%. But the market was gripped by a case of “he said, Xi said” in May: comments from President Trump and President Xi raised the prospects of tit-for-tat tariffs and led the S&P 500 to a 6.4% monthly decline.

Over the summer, Jerome Powell’s comments that the Fed would “act as appropriate to sustain the expansion” heralded a return to bad news is good news. Underwhelming economic data fueled expectations for future rate cuts, which in turn were expected to have a positive impact on equities. This supported the S&P 500 during its best June performance since 1955 – its 7.1% monthly gain also coincided with optimism that trade tensions would ease after the U.S. and China met at the June’s G20 summit.

More recently, the market put its disappointment about July’s “mid-cycle adjustment” in the rear-view mirror: the S&P 500 recorded 6 consecutive weekly gains as the market got the rate cuts it expected, earnings largely beat expectations, and trade tensions eased.

2020 to be a stock-pickers market? Maybe not

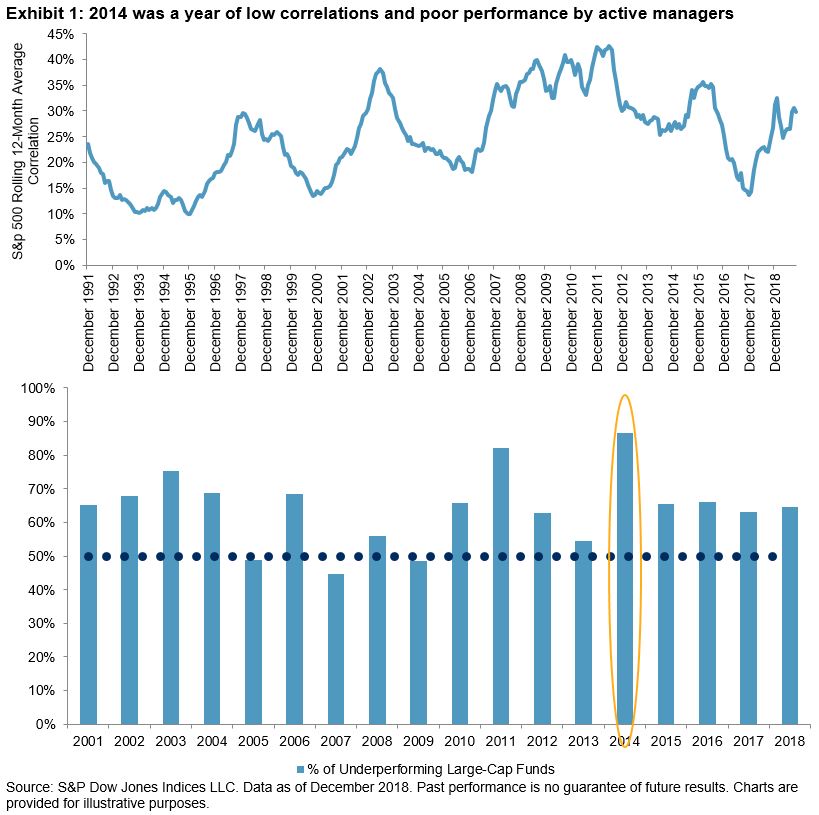

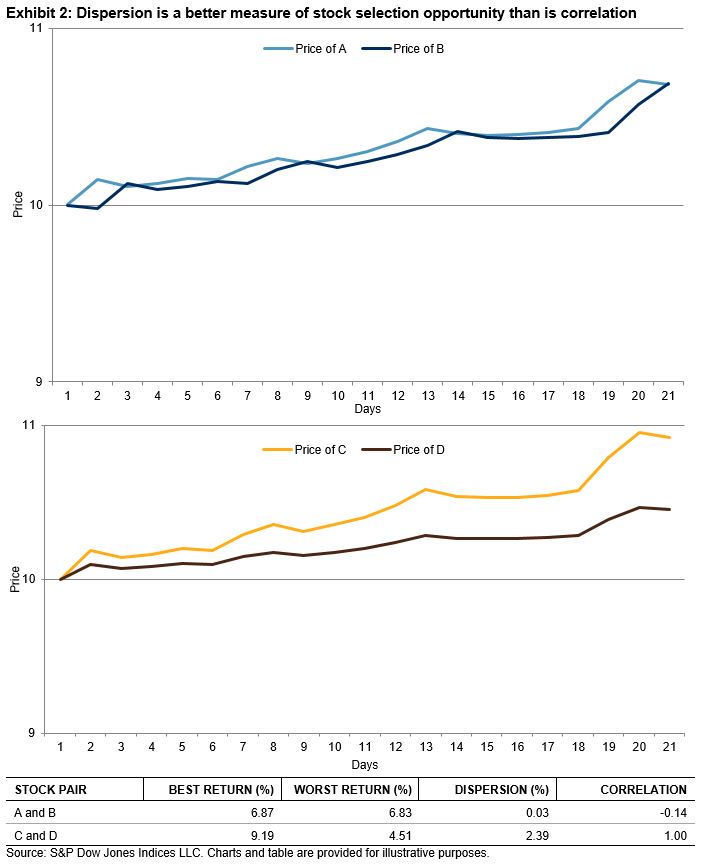

The idiosyncratic reactions of companies to the various drivers of recent market returns has contributed to a decline in correlations. Some have argued that this means 2020 will be the year of the stock-picker, but this argument is not new: hope springs eternal for active managers.

As we have shown before, a better measure of active management’s alpha opportunity is dispersion: a greater proportion of large-cap active managers typically underperformed the S&P 500 when dispersion was lower. Given U.S. large-cap dispersion has remained subdued so far this year, the current environment may pose challenges for many large-cap active managers.

Thank you, Jack Bogle!

Finally, no review of 2019 would be complete without a mention of one of the titans of indexing, John C. Bogle, who died in January. In the words of Warren Buffett:

“If a statue is ever erected to honor the person who has done the most for American investors, the hands-down choice should be Jack Bogle”.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.