In investing, risk and return are two sides of the same coin; the expected returns of an asset must be accompanied by variation or uncertainty around the outcome of those returns. All else equal, higher-risk assets should be compensated, on average, by higher returns. The same philosophy applies to performance evaluation. The performance of both active and passive funds should be evaluated in proportion to the risks taken to achieve those returns.

Our Risk-Adjusted SPIVA® Scorecard examines the performance of actively managed funds against their benchmarks on a risk-adjusted basis, using both net-of-fees and gross-of-fees returns. We used the standard deviation of monthly returns over a given period to define and measure risk. The return/risk ratio looks at the relationship and the trade-off between risk and return. All else equal, a fund with a higher ratio is preferable since it delivers a higher return per unit of risk taken. To make our comparison relevant, we also adjusted the returns of the benchmarks used in our analysis by their volatility.

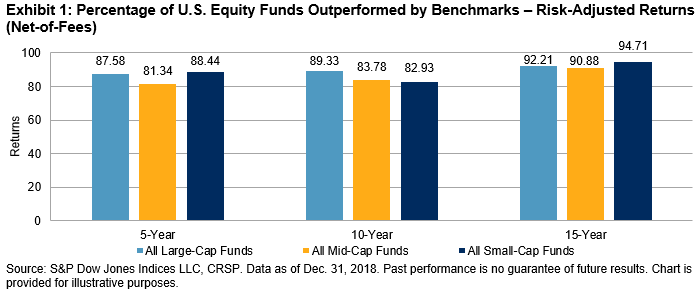

After adjusting for risk, the majority of actively managed domestic funds in all categories underperformed their benchmarks, net-of-fees, over mid- and long-term investment horizons. Although the risk-adjusted performance of active funds improved compared to their benchmarks on a gross-of-fees basis, real estate was the only fund category that generated a higher ratio than the benchmark over the five-year period. Overall, the majority of active domestic equity managers in most categories underperformed their benchmarks on a gross-of-fees basis.

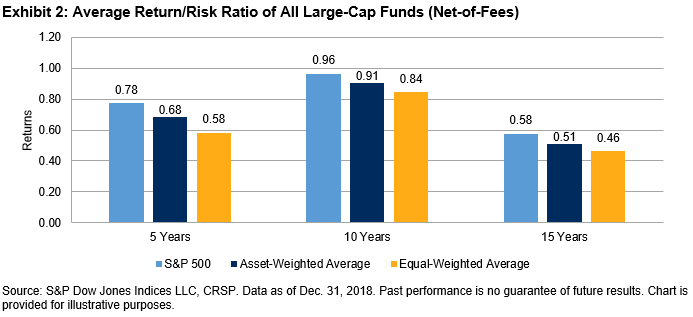

Asset-weighted return/risk ratios of active managers were higher than their equal-weighted counterparts, indicating that larger firms tend to take on better compensated risk than smaller firms (see Exhibit 2). When comparing average ratios against their benchmarks, all domestic equity categories had lower ratios across all investment horizons when they were equally weighted on a net-of-fees basis. However, asset-weighted ratios of real estate funds (over the 5-, 10- and, 15-year periods), large-cap value funds (over the 10- and 15-year periods), mid-cap growth funds (over the 5-year period), and mid-cap value funds (over the 10-year period) were higher than the benchmarks.

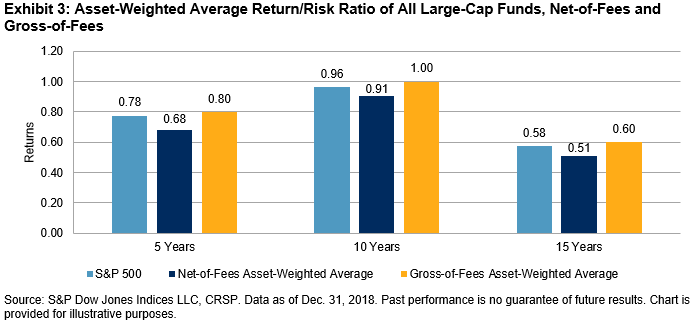

The impact of fees on active managers’ risk-adjusted returns was substantial. For example, on a gross-of-fees basis, the asset-weighted average return/risk ratios of all large-cap funds exceeded the benchmarks across all investment horizons. However, the advantage diminished quickly when fees were taken into consideration (see Exhibit 3).

Our analysis dispels the myth that active management possesses better risk-management skills than passive indices. Moreover, any perceived advantage in higher risk-adjusted returns quickly disappears once fees are accounted for.

For more information on the risk-adjusted performance of actively managed funds compared with their benchmarks in 2018, read our latest Risk-Adjusted SPIVA Scorecard.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.