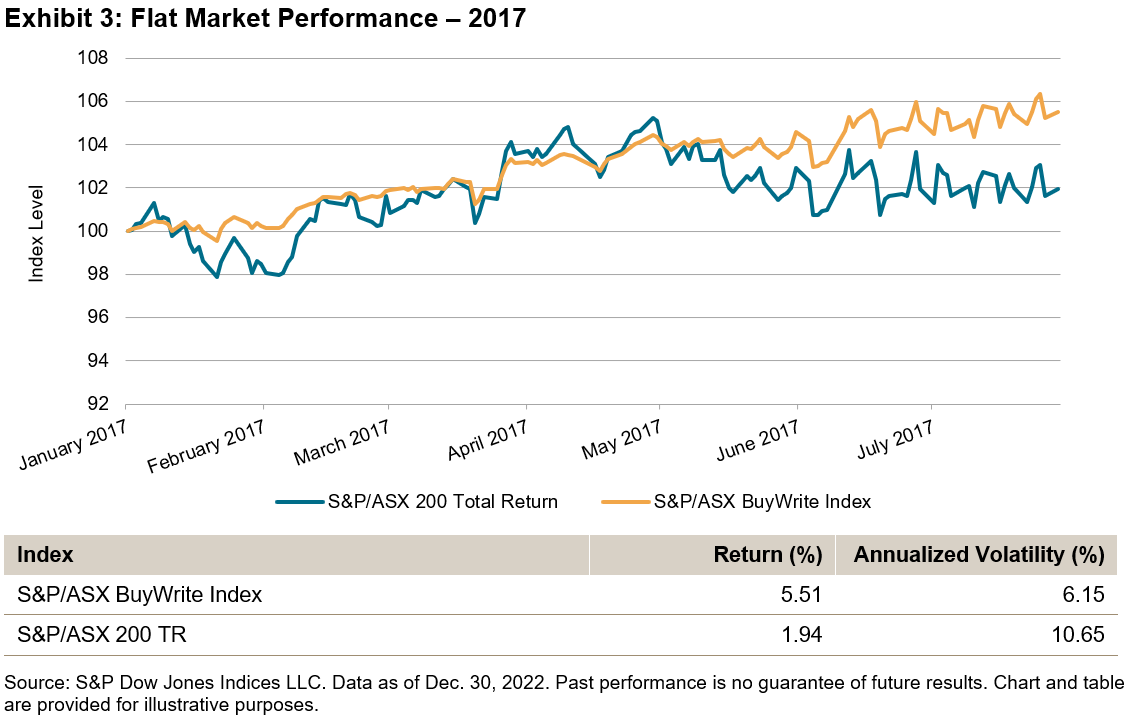

The volatile and unpredictable nature of the stock market is characterized by periods of ups and downs. Covered call option writing is a strategy aimed at generating income and mitigating loss, particularly in bear market environments. A covered call (or “buy-write”) strategy involves selling a call option against an asset that is already owned by the option writer. If the asset’s market price exceeds the strike price of the contract, a rational call option buyer would exercise the option. This would then obligate the asset owner to sell the asset at the strike price to the option buyer. If the strike price is not met, the owner maintains possession of the asset. In either case, the asset owner keeps the profits from selling the call contract—known as the “option premium.”

One factor that influences the premium received from selling a call is the “option moneyness;” that is whether the option contract is “in the money” (ITM), “out of the money” (OTM), or “at the money” (ATM). An OTM call has a strike price that is above the current market price. An ATM call has a strike price that is equal to the current market price of the asset—this generates a higher premium, as there is a greater chance that the option will be exercised at this price.

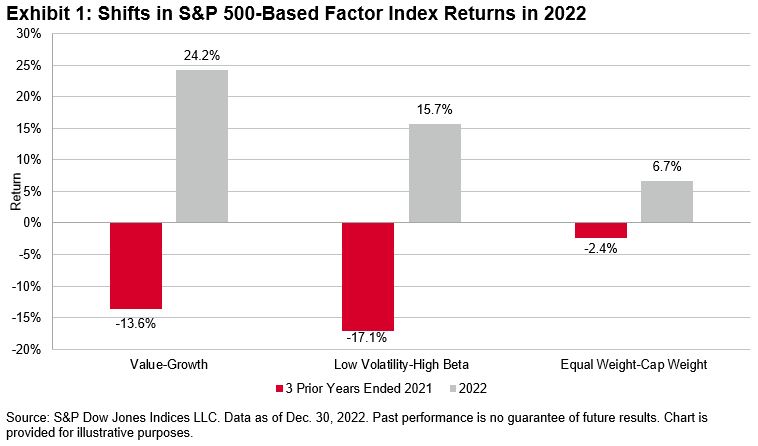

A major drawback of the covered call strategy occurs if a call option is “in the money” and the buyer exercises their option to purchase the underlying asset at the below-market strike price. The option writer would miss out on any gains that the asset may achieve beyond the strike, as they will be forced to sell the asset at this lower price, therefore capping the asset’s growth potential (see Exhibit 1). A long-term covered call strategy can help make up for this by offering consistent income that can be used to reinvest into the asset.

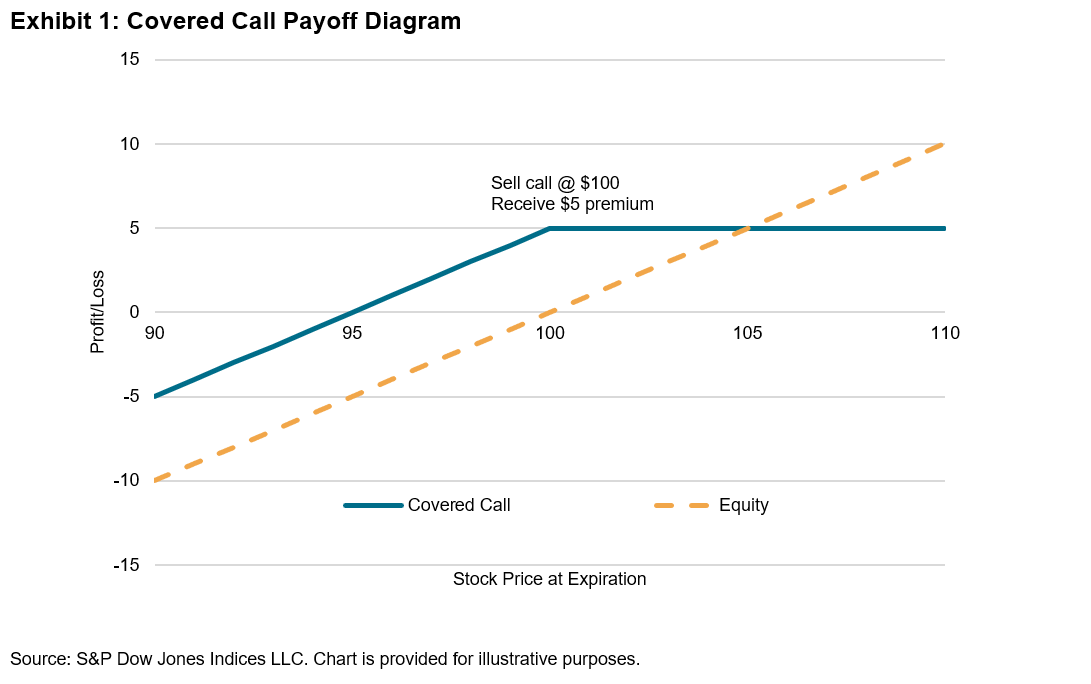

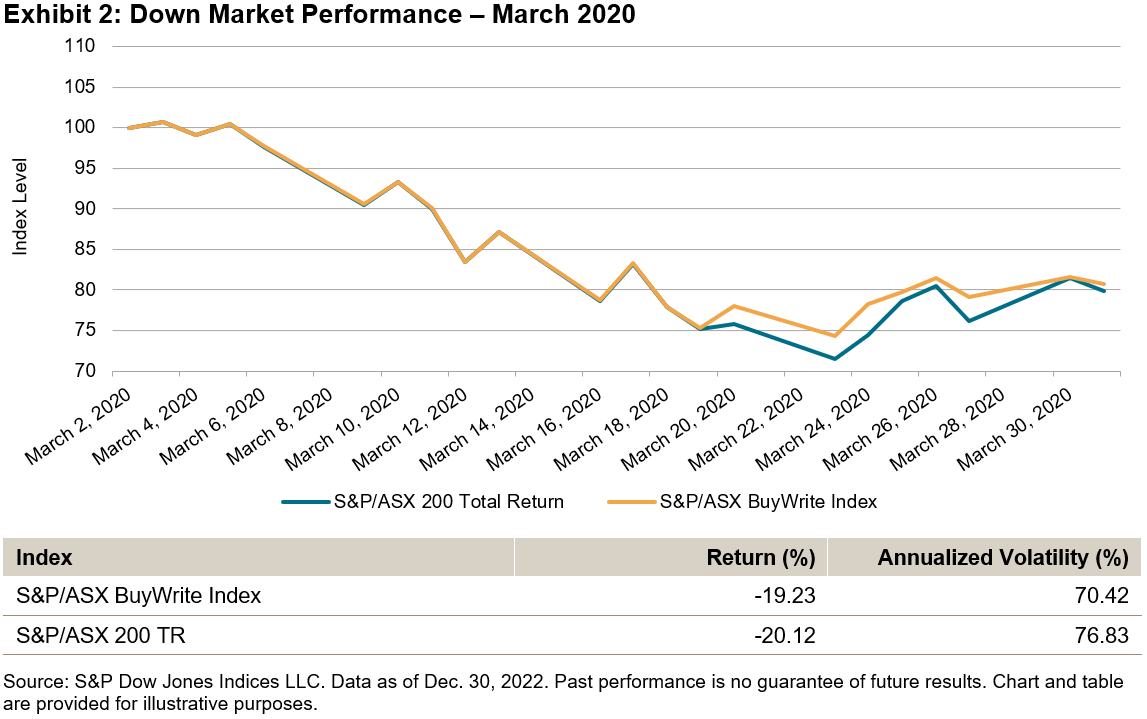

The S&P/ASX BuyWrite Index was launched in May 2004. It employs a covered call methodology in which the index holds a long position on the underlying S&P/ASX 200 while selling quarterly at-the-money calls on this position.

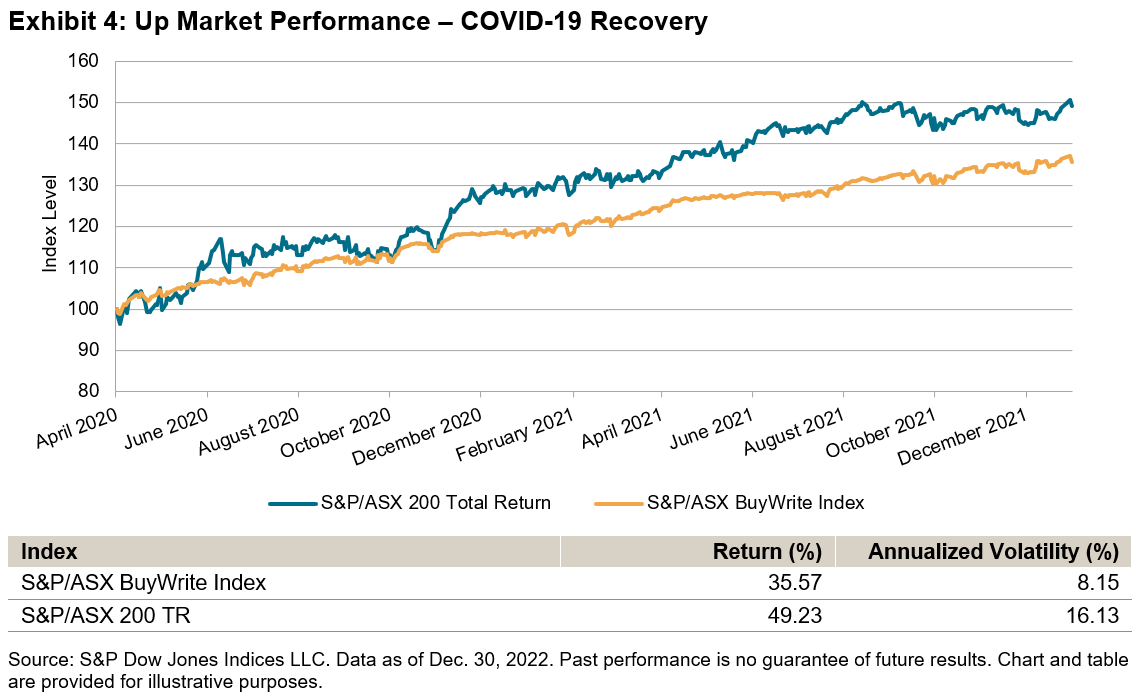

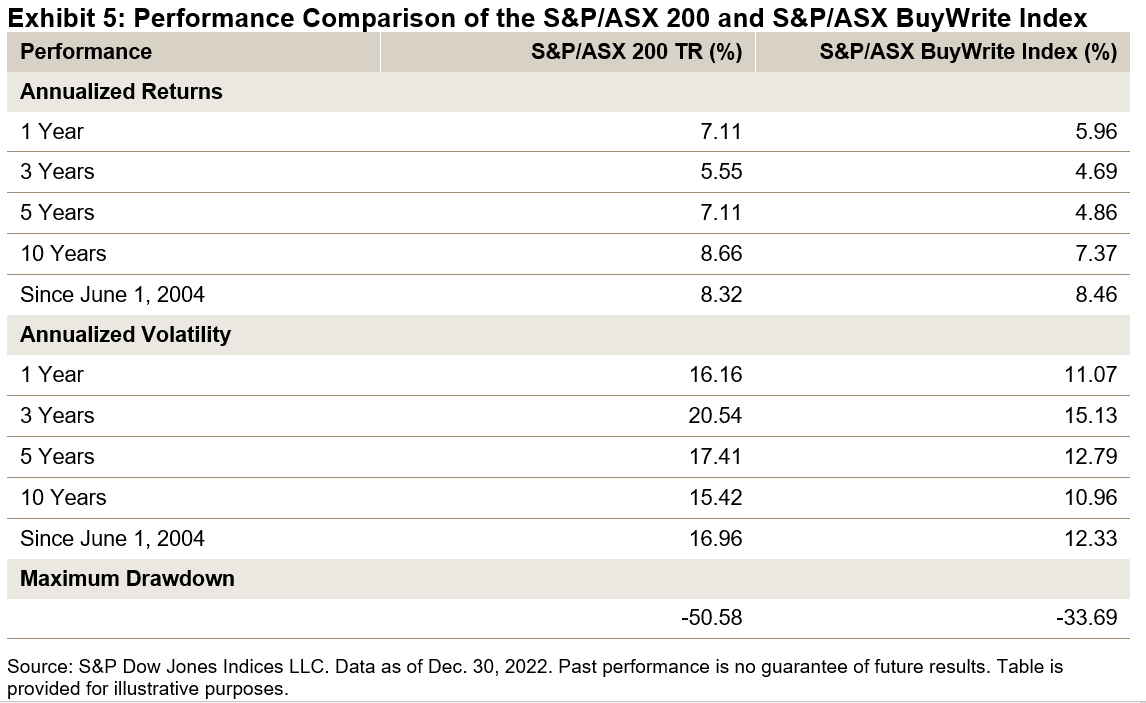

The S&P/ASX BuyWrite Index seeks to track the equity assets of the underlying index and the dividends they provide, while also generating additional income from accumulated option premiums. These premiums are reinvested into the long equity position. This has enabled the buy-write index to outperform the underlying equity index historically in a down, neutral or moderately up market (see Exhibits 2 and 3). In turn, the index has underperformed the underlying equity index during periods of strong rallies due to its capped upside potential (see Exhibit 4). Long-term live performance of the S&P/ASX BuyWrite Index is competitive with that of the S&P/ASX 200 (see Exhibit 5). The consistent reinvestment of option premiums has historically helped reduce the volatility of the covered call index compared to its underlying index (see Exhibit 5).

In the next blog, we will dig into the income-generating feature of this index. Stay tuned!

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.