The fast-changing nature of the ESG landscape is no stranger to those within it. Competing definitions, variability in scoring methodologies, and a spectrum of individual investor objectives have made fertile ground for divergent approaches. However, among this slew of sustainable investment strategies, common threads have emerged. When the S&P 500 ESG Index was launched in January 2019 as an accessible starting point for ESG investors around this world, it did so by excluding the types of business activities deemed unacceptable by the broadest possible majority of sustainability-minded investors and selecting constituents according to their relative S&P DJI ESG Score performance within index and industry groups. At the time, this meant avoiding companies involved in controversial weapons and tobacco, in addition to other sustainability screens not specifically tied to business involvement.1 Just over 19 months later, the landscape has evolved to a point at which thermal coal companies may now be counted among this lowest common denominator of “unsustainable” investments. Thus, after an industry-wide, public consultation that confirmed this shift in investor perception, the S&P ESG Index Series Methodology was updated to exclude thermal coal in an extraordinary rebalance that took effect on Sept. 21, 2020.2

Rebalance Results

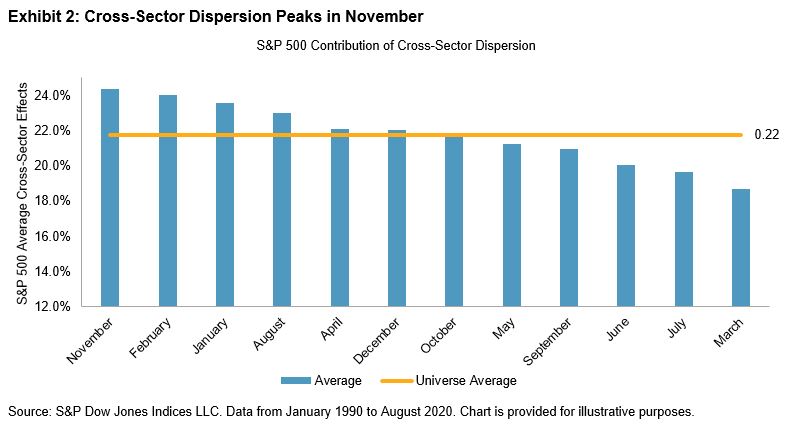

As of the rebalance, 299 constituents made it into the S&P 500 ESG Index, with 78 ineligible companies and 125 deemed eligible but not selected due to relatively poorer S&P DJI ESG score performance compared with their index industry group peers. Exhibit 1 shows how the S&P 500 now translates into the composition of the S&P 500 ESG Index.3

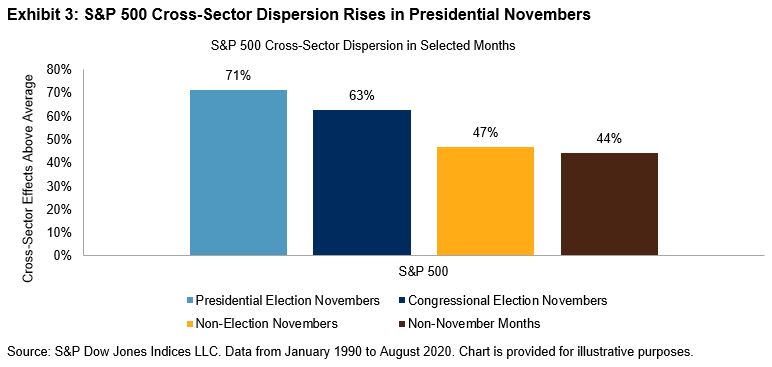

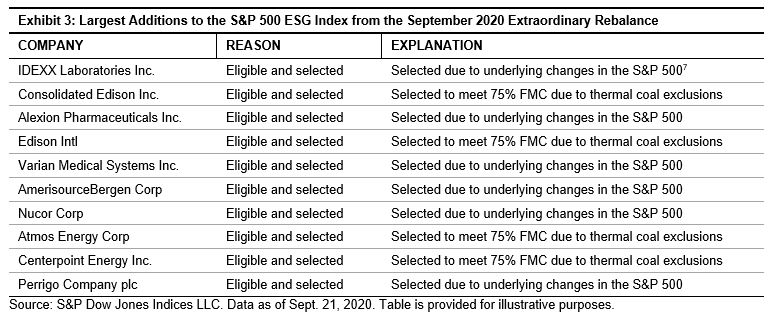

But what’s really changed? Unsurprisingly, the changes were primarily driven by companies removed due to having more than 5% of their revenues coming from thermal coal, as defined by the new exclusion rule.4 However, only 11 of the 17 thermal coal companies within the S&P 500 were dropped from the S&P 500 ESG Index, as the rest were already excluded due to one of the preexisting exclusion and selection criteria. Subsequently, 4 names were added, as these departures made room for new joiners and the methodology must target 75% of the float-adjusted market cap (FMC) within index and industry groups (where companies are ranked by S&P DJI ESG Score).5 A further 10 companies were dropped as they were no longer required to target 75% FMC within their index industry groups—unrelated, specifically, to the removal of thermal coal companies. Eight new names were thus added due to non-thermal coal exclusion-related changes in the S&P 500. Exhibits 2 and 3 outline the largest 10 additions and drops in order of market capitalization.

Impact of Removing Thermal Coal

To properly assess the impact of excluding thermal coal companies, the index objective has to be considered. The S&P 500 ESG Index is designed to reflect a sustainable, broad-based measurement of the U.S. equities market, with similar overall industry group weights as the benchmark S&P 500. As such, changes to the methodology need to be evaluated in the context of its implicit goal of keeping the tracking error low. As part of the consultation, data showing the realized tracking error of the S&P 500 ESG Index versus the S&P 500 between the 2019 and 2020 annual rebalances (1.08%) was thus compared to the hypothetical results that would have occurred had the new 5% thermal coal exclusion rule been in effect (1.11%).8 Based on this analysis, the removal of thermal coal companies does not appear to diminish the index’s ability to meet its objective. This important result, alongside the positive response from market participants generally in favor of the new rule, underpinned S&P DJI’s decision to implement this change. This decision reflects S&P DJI’s ongoing commitment to creating ESG indices to match investor conviction, as the lines surrounding the sustainable investment landscape continue to be drawn.

1 The S&P ESG Index Series Methodology additionally excludes companies that perform poorly on the principles of the UN Global Compact (UNGC), companies involved in controversies deemed material to their ESG performance (according to the SAM Media & Stakeholder Analysis [MSA]), as well as companies that rank among the bottom 25% of S&P DJI ESG Scores, globally. As of Sept. 21, 2020, companies with more than 5% of revenues generated from thermal coal were added to the list of ineligible companies for the index series.

2 The public consultation, which ran from March 23, 2020, to May 29, 2020, outlined several options for the proposal and their potential impacts, which may be found here. As most respondents were generally in favor of excluding companies with more than 5% of revenues generated from thermal coal, the S&P DJI Index Committee announced on June 12, 2020, its decision to implement this new rule via an extraordinary rebalance that would take effect on Sept. 21, 2020. Following this rebalance, the index will return to its normal schedule of annual rebalances, effective after the close of the last business day of April.

3 For more information about the last official annual rebalance in April 2020, please refer to this May 2020 blog announcing the changes. Deeper dive analysis examining the impacts of the S&P 500 ESG as of the April 2020 annual rebalance can also be found in our recently published piece “The S&P 500 ESG Index: Defining the Sustainable Core.”

4 The consultation asked market participants whether the S&P ESG Index Series Methodology should exclude companies with revenues generated from thermal coal, and if so, whether the appropriate revenue threshold should be set at 25%, 10%, or 5%. S&P DJI opted to select the strictest measure based on the consultation results.

5 For more information about the index series methodology, including how it targets 75% FMC within index industry groups, please refer to the S&P ESG Index Series Methodology.

6 Other household names dropped from the index include News Corp and H&R Block. News Corp was eligible but no longer required to target 75% FMC within its index and industry group. H&R Block was dropped due to underlying changes in the S&P 500.

7 Companies added due to underlying changes in the S&P 500 were added either due to changes in the underlying constituents comprising the index industry group, or due to existing constituents losing market capitalization, essentially requiring additional companies be added when targeting 75% FMC.

8 Data from April 30, 2019 to April 30, 2020.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.