Prior research has demonstrated that profitability matters for small-cap companies in the U.S. and in global equity markets. For example, the S&P SmallCap 600®—which includes an earnings eligibility criteria—has outperformed the broader Russell 2000 Index (with lower volatility) over its 25-year track record.

Our new S&P/TSX SmallCap Select Index extends this phenomenon to Canadian equities, where we have found that a similar effect exists. Simply put, filtering out the “junk” makes a big difference in Canadian small caps. Exhibit 1 illustrates the total return improvement and volatility reduction of the S&P/TSX SmallCap Select Index versus the broader S&P/TSX SmallCap Index over the past 15 years.

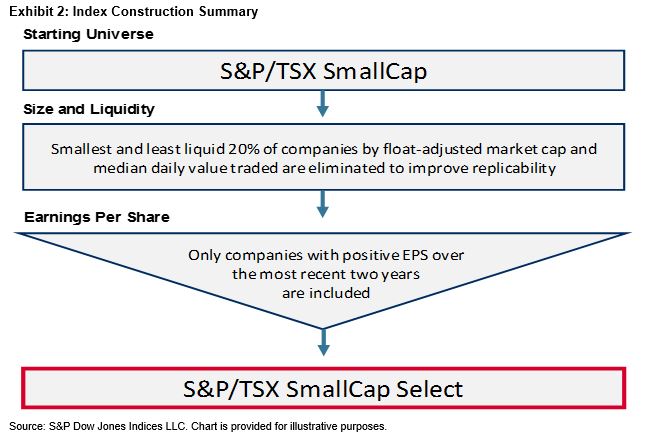

How Does the S&P/TSX SmallCap Select Index work?

The index follows the same methodology framework as our existing S&P SmallCap Select Index Series, but uses the S&P/TSX SmallCap Index as its selection universe. In order to be eligible for index inclusion, companies must post two consecutive years of positive earnings per share. As a buffer, companies are dropped from the index after posting two consecutive years of negative earnings. In order to improve replicability of the index, we also eliminate the 20% smallest and 20% least liquid companies. The index is weighted by float market cap and is rebalanced semiannually in June and December.

As of the June 2019 index rebalancing, the S&P/TSX SmallCap Select Index included 100 of the 199 companies in the S&P/TSX SmallCap Index and captured about 65% of the float market cap of the benchmark index. As shown in Exhibit 3, the majority of the exclusions were driven by the positive earnings requirement.

To learn more about the impact of including a positive earnings requirement in Canadian small caps, please see our recently published short paper that introduces the S&P/TSX SmallCap Select Index.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.