After wreaking havoc on the municipal bond markets, Puerto Rico bonds have recently been adding value through their recovery. Bonds rallied after the latest debt restructuring deal was struck between the commonwealth and the bond holders. Additional supporting news, as mentioned in an article from Reuters,[1] was a federal court ruling affirming the budgetary powers and enforcement of fiscal discipline by the federal oversight board that was created by the 2016 federal PROMESA Act.

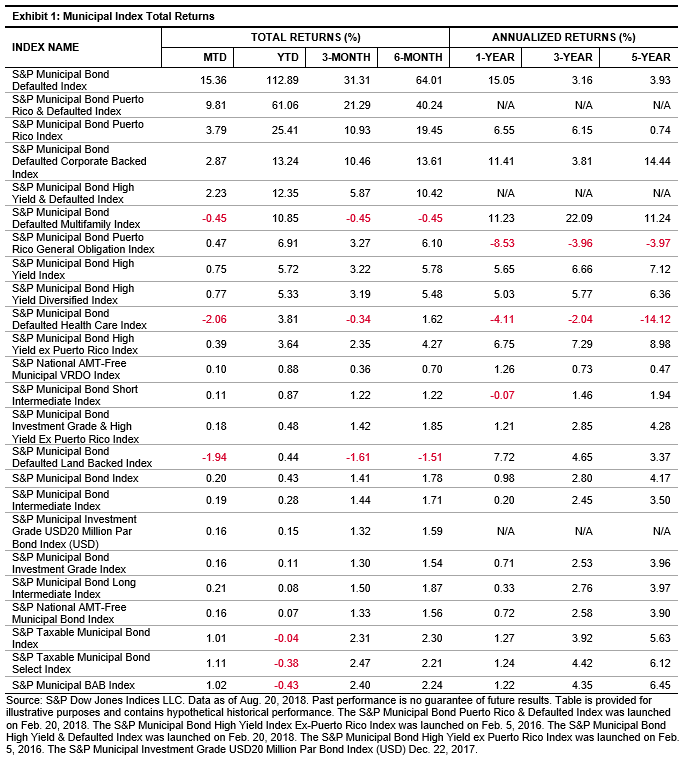

These recent developments have led to positive returns for indices containing Puerto Rico bonds. As of Aug. 20, 2018, the S&P Municipal Bond Puerto Rico Index returned 25.4% YTD and the S&P Municipal Bond Puerto Rico & Defaulted Index returned 61% YTD.

The S&P Municipal Bond High Yield Index, which contains Puerto Rico bonds (with a weight of 9.3%), returned 5.72% YTD, while the S&P Municipal Bond High Yield ex Puerto Rico Index returned 3.64% YTD—2% less for excluding Puerto Rico bonds.

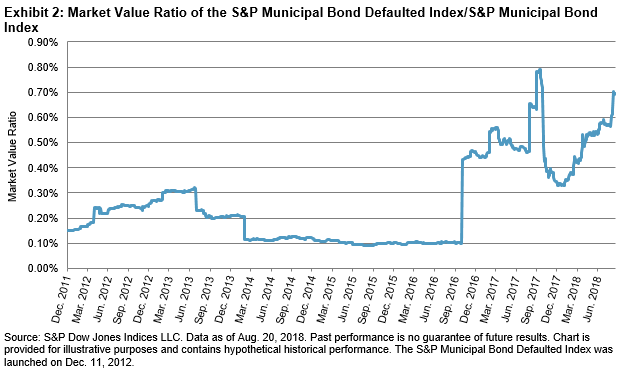

The S&P Municipal Bond Defaulted Index is a universe of bonds considered to be in monetary or technical default. Defaults are currently 0.70% of the broad benchmark S&P Municipal Bond Index, averaging 0.26% over the history of the two indices. This ratio has been as low as 0.09% during the summer of 2015 and as high as 0.79% from Sept. 13 to Sept. 18, 2017.

The month-end rebalance for September 2016 saw the market value of the default index jump from USD 1.7 billion to USD 7.6 billion, as 110 bonds (92 of which were Commonwealth of Puerto Rico bonds) moved into the default realm. Index rebalancings similar to September 2016 also occurred Jan. 31 and July 31, 2017.

Currently Puerto Rico bonds account for 92% of the default index, so as Puerto Rico bond prices go, so goes the S&P Municipal Bond Defaulted Index, which is up 15.4% MTD as of August 20, 2018.

As mentioned in a Seeking Alpha article, “Muni bonds, in general, are second only to U.S. Treasuries in terms of perceived safety. Headline-grabbing though the above cases may be, municipal bond defaults remain extremely rare. In the period from 1970 through the end of 2015, out of the thousands of muni bonds issued across the country, there were just 99 defaults. That translates into an annual default rate of 0.09% for all-rated municipal bonds throughout the 46-year period. In fact, investment grade “Aaa” and “Aa” rated munis experienced zero defaults.”[2]

[1] Reuters, “Puerto Rico bond prices surge as restructuring deals struck”

[2] Seeking Alpha, “Municipal Defaults, While Rare, Do Occur”

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.