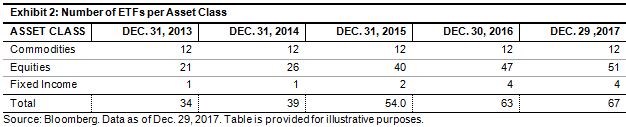

Until 2013, the exchange-traded fund (ETF) industry in India was in a nascent stage, with negligible assets under manager (AUM). As of Dec. 31, 2013, the total AUM for ETFs was INR 8,000 crores (or USD 1.2 billion), out of which commodities-based ETFs tracking gold noted the largest share, with total AUM of INR 6,500 crores (USD 1 billion). Starting with such a small base, the ETF industry noted exponential growth over the past four years, primarily driven by a decision from the Employee Provident Fund Organization (EPFO, one of the largest pension houses in India) to start investing in equities-based ETFs, including those tracking the S&P BSE SENSEX, as well as the Government of India’s decision to disinvest its holdings via ETFs.

As of Dec 31, 2017, the total AUM of the ETF industry stood at INR 78,000 crores (USD 12 billion), with an annualized growth rate of 76.6% during the past four years. The industry saw four new product launches in 2017, including the Bharat 22 ETF, which tracks the S&P BSE Bharat 22 Index and had the largest (by AUM) single ETF launch ever worldwide. This ETF was part of the disinvestment of listed government-owned companies in India.

Exhibit 1: Growth of ETF AUM – India

Among the three asset classes, equities noted the highest increase, with an annualized growth of 213% over the past four years. The exponential growth was also supported by a sustained bull run in Indian and global markets, with the S&P BSE SENSEX, S&P BSE MidCap Select, and S&P BSE SmallCap Select increasing 29.56%, 53.23%, and 51.13%, respectively over calendar year 2017.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.