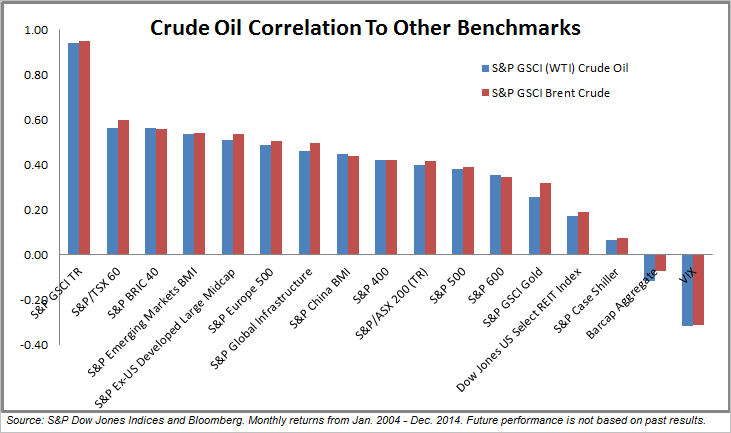

The unprecedented drop in oil prices has been a driver of global economic worries. As of Jan. 16, 2015, the total return of the S&P GSCI Crude Oil is down 8.89% MTD, after closing out 2014 down 42.5%.

As of the same date, the S&P U.S. Issued Investment Grade Corporate Bond Index has returned 1.76% MTD, as the energy sector accounts for only 8% of market value for this index. In comparison, the energy sector of the S&P U.S. Issued High Yield Corporate Bond Index has returned 14% MTD and reached 17.6% in October 2014.

The S&P U.S. Issued High Yield Corporate Bond Index has returned 0.08% MTD as of Jan. 16, 2015, but the index would be returning 0.32% without its energy sector. In regard to credit ratings and issuers, this index is similar to the S&P/LSTA U.S. Leveraged Loan 100 Index, which has returned 0.16% MTD.

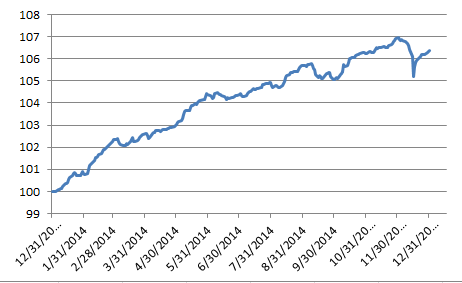

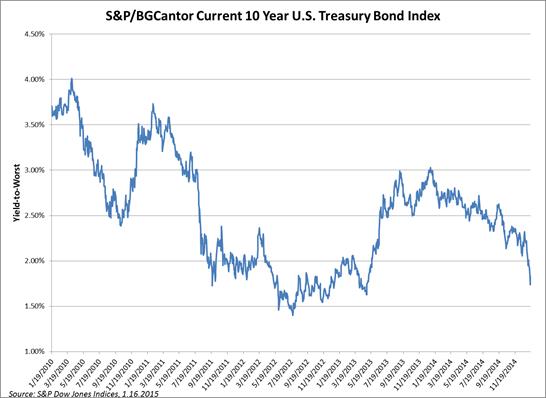

The yield on the U.S. 10-year Treasury bond, as measured by the S&P/BGCantor Current 10 Year U.S. Treasury Index, tightened by 13 bps to close at 1.83% on Jan. 16, 2015. This closing rate, before the U.S. holiday on Monday, was in stark contrast to the prior day’s yield of 1.74%. To match a 1.74% yield on the U.S. 10-year Treasury bond, we would have to look all the way back to May 2013.

Recently, the U.S. 10-year Treasury bond has been trading at 1.76%, as the market speculates that the European Central Bank (ECB) will start buying more bonds as part of its stimulus package. Relative to European bonds, yields in the U.S. look attractive for European investors, as their domestic yields have been reaching record lows. The yield of a German 10-year treasury bond is approximately 0.44% at this time, while the forex quote on U.S. dollar-to-euro rate is USD 1.156. The currency exchange, which had dropped from USD 1.39 in March 2014 to a year-end value of USD 1.209, has continued its trend as the U.S. dollar continues to strengthen.

Exhibit 1: S&P/BGCantor Current 10 Year U.S. Treasury Index Yield-to-Worst

Source: S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC. Yield-to-worst levels as of Jan. 16, 2015. Charts and tables are provided for illustrative purposes only. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.