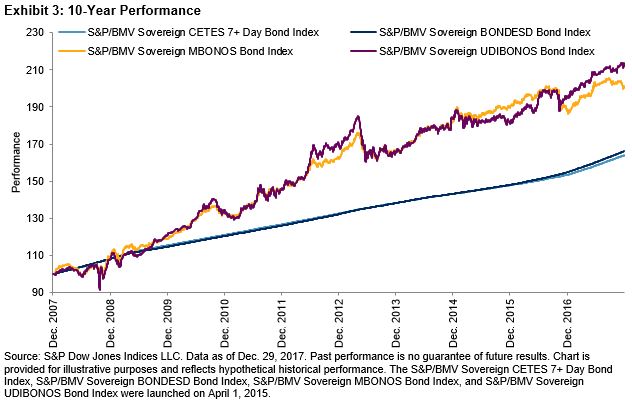

Gross issuance of green bonds reached USD 157 billion in 2017, nearly double that of the previous year. Fourth quarter issuance was the fastest quarterly pace on record, adding USD 48 billion, 30% more than seen in each of the previous three quarters.

Issuers and issuance types continue to diversify. Asset-backed security (ABS) issuance had the largest year-over-year increase, accounting for USD 36 billion (23% of gross 2017) of total issuance, up from USD 8.6 billion (8.6% of gross 2016). Development Banks, which historically have been the dominant issuers, issued USD 21 billion (14% of gross 2017), down from USD 24 billion (28% of gross 2016) the previous year. Sovereign issuance, which began with Poland in December 2016, has grown to USD 14 billion as of March 2018, with French Treasury, Fijian, Nigerian, Belgium, and Indonesian sovereign bonds. Hong Kong outlined a grant for first-time green corporate bond issuers and plans to issue the largest amount of green sovereign bonds this year.

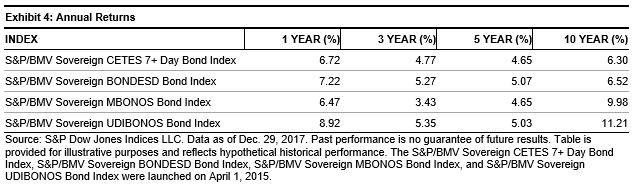

Despite steady persistence of issuance from China, the U.S. took the top spot in 2017, driven by the increase in ABS issuance. China, a latecomer to the green bond market, took second place, despite the outsized sovereign issuance by the French government, and held on to its third place spot in total issuance.

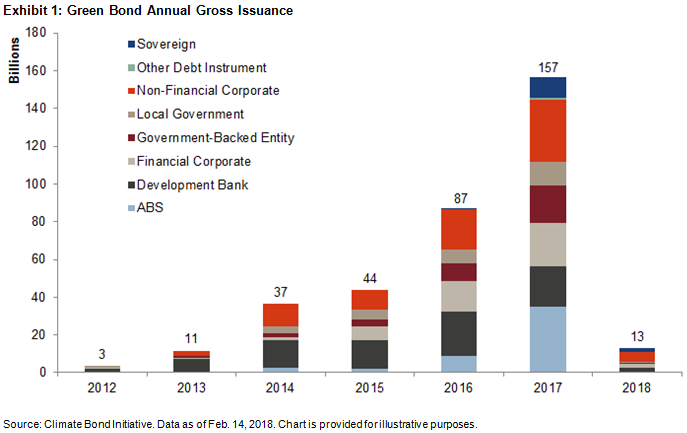

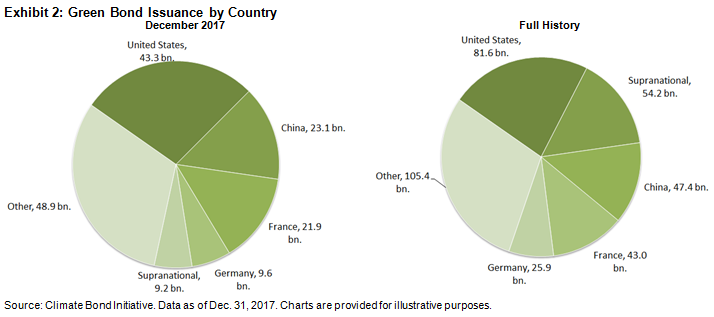

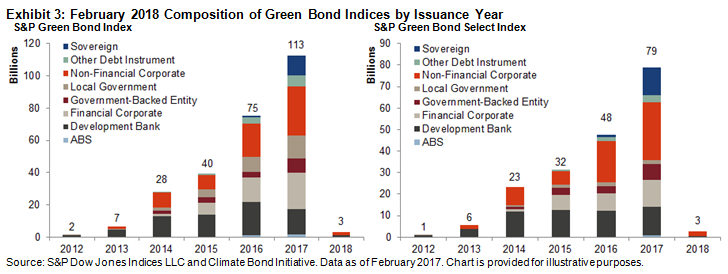

USD 113 billion of the primary issuance in 2017 qualified for the S&P Green Bond Index, which is designed to track the global green bond market. The primary inclusion rule for the broad index is price availability—currently, the USD 26.3 billion of Fannie Mae ABS issuance is not being included. Of the bonds included in the broad index, 70% by market value qualified for the S&P Green Bond Select Index. This narrower index further limits inclusion with more stringent financial and extra-financial eligibility criteria (see Exhibit 3).

The S&P Green Bond Select Index can help diversify core fixed income exposure away from treasuries. Despite the ramp up in sovereign issuance, agencies, supras, and local authorities account for the lion’s share of the S&P Green Bond Select Index, representing 60% of the index, while treasury bonds constitute less than 6%. In comparison, core fixed income markets are primarily made up of treasuries. For example, in the Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Bond Index, treasuries make up about 60% of the index.

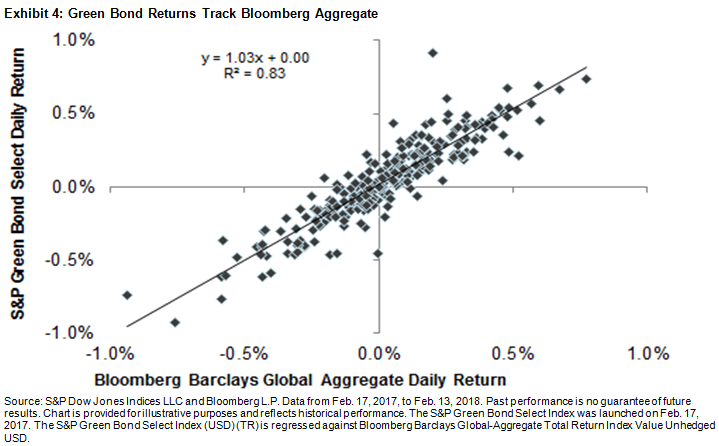

Investors looking to add an element of green exposure to their core portfolio may be able to replace a portion of their global aggregate bonds with green bonds without sacrificing performance. Despite the differences in composition, historical performance of green bonds has been much like the aggregate index. Over the past year, when regressing the daily returns of the S&P Green Bond Select Index against the Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate, there was a 0.91 correlation, with a statistically significant (at 95%) slope of 1.03, and a small positive alpha (see Exhibit 4). That means that market participants looking to green up their portfolio may not need to sacrifice performance to do so.