In the inaugural publication of the Journal of Portfolio Management in 1974, Nobel Laureate Paul Samuelson wrote that there is no “brute fact” that “there could exist a subset of decision makers in the market capable of doing better than the averages on a repeatable, sustainable basis.”[1] That article partly inspired John Bogle to launch the first index mutual fund.[2] Even though over four decades have passed since Paul Samuelson penned the article, his words remain relevant to today’s world of investing.

This year marks the 15th anniversary of S&P Dow Jones Indices publishing the SPIVA® U.S. Scorecard. A lot has changed in the asset management industry since we started reporting on the active versus passive debate. The proliferation of index-linked investment products and the low-cost, efficient ways they can provide exposure to desired asset classes and markets have been disruptive, adding a tremendous amount of pressure on active managers in terms of fees and performance. At the same time, the line between what has traditionally been considered beta versus alpha has blurred, with the passive side continuing to innovate and replicate strategies that once sat predominantly in the active realm.

Amid that shifting landscape, the SPIVA Scorecard has maintained its objective voice as an independent scorekeeper of the active versus passive debate. It has demonstrated that over a long-term investment horizon, average active managers across market cap segments and styles have underperformed their respective benchmarks. Exhibit 1 shows the rolling three-year relative performance of actively managed domestic large-, mid-, and small-cap funds against their respective benchmarks[3].

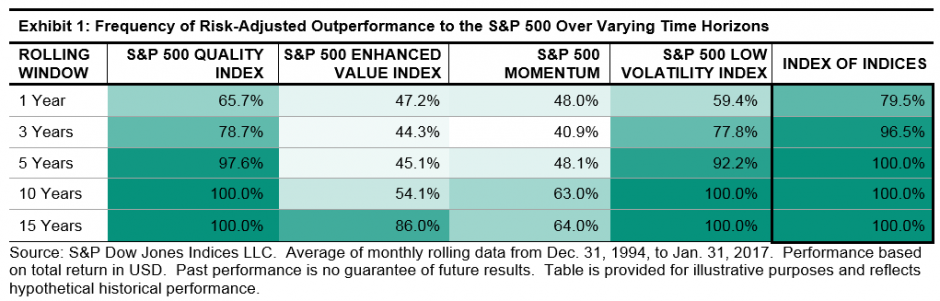

Moreover, the outperformance that winning active managers have generated has been shown to be fleeting. Through a number of studies, we have found that managers that outperform their benchmarks in a given year or are in the top quartile of their peer groups are unlikely to repeat their winning streak repeatedly.[4] For example, we studied over 789 large-cap, 383 mid-cap, and 511 small-cap funds on average on a rolling quarterly basis from March 31, 2003, to Sept. 30, 2016 (see Exhibit 2). We found that out of the 20%-30% of funds that outperformed their benchmark in a given year, only a small subset were able to repeat that outperformance in the subsequent three years (see Exhibit 2).[5]

Taken together, these findings indicate that market participants may face substantial difficulty in identifying a winning manager in advance. They also pose the challenging question of how one should go about measuring the success of active management. If net-of-fees returns (and, in many equity markets, gross-of-fees returns)[6] are not high enough to overcome benchmark returns across all market cycles and the outperformance produced is fleeting, what should constitute the evaluation framework for active management?

With that, the active versus passive debate turns a new chapter. Given that fees contribute partly to managers’ underperformance,[7] it seems clear that closet indexing at high costs cannot be sustainable. For active management to add value and separate themselves from passive strategies, focusing on differentiated portfolio construction or strategies in which managers take compensated bets, along with outcome-oriented investment solutions, can serve as ways to promote their skills.

Only time will tell whether these differentiated strategies can deliver higher risk-adjusted returns than their passive counterparts. It seems clear that the active versus passive debate is evolving and heading in a new direction in which active management could become more active.

[1] Paul Samuelson, “Challenge to Judgement”. The Journal of Portfolio Management 1974.

[2] John C Bogle, “Lightning Strikes: the Creation of Vanguard, the First Index Mutual Fund, and the Revolution It Spawned”. The Journal of Portfolio Management. Special 40th Anniversary Issue

[3] See the SPIVA U.S Year-End 2016 Scorecard

[4] See the Persistence Scorecard.

[5] See Fleeting Alpha: Evidence from the SPIVA and Persistence Scorecards.

[6] See Institutional SPIVA Scorecard – How Much Do Fees Affect the Active Versus Passive Debate?

[7] See Institutional SPIVA Scorecard – How Much Do Fees Affect the Active Versus Passive Debate?

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.