In my last blog, we discussed the performance characteristics of the S&P/ASX BuyWrite Index. We will now focus on the income-generating feature of this index.

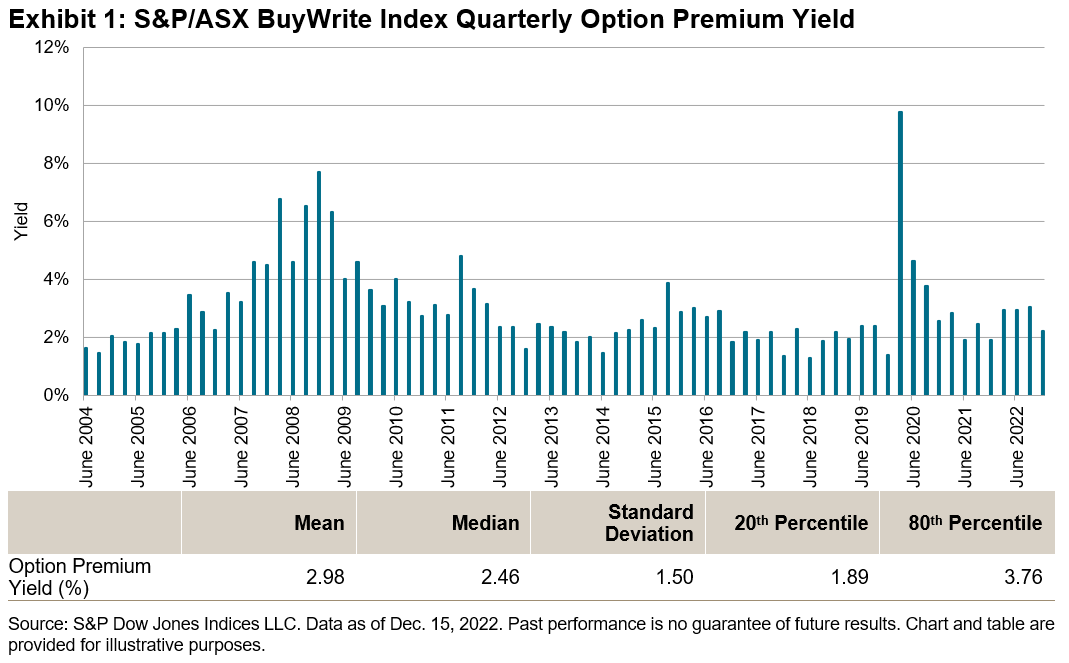

As a reminder, a covered call strategy involves selling a call option against an asset that is already owned by the option writer. A systematic long-term covered call strategy generates a steady income stream through the accumulation of option premiums. The S&P/ASX BuyWrite Index employs such a strategy by selling quarterly at-the-money calls against a long position in the underlying S&P/ASX 200. Since its launch in 2004, the index has achieved an average quarterly option premium yield of 2.98%, with yields peaking during the bear markets of the Great Financial Crisis of 2008 and March 2020 (see Exhibit 1).

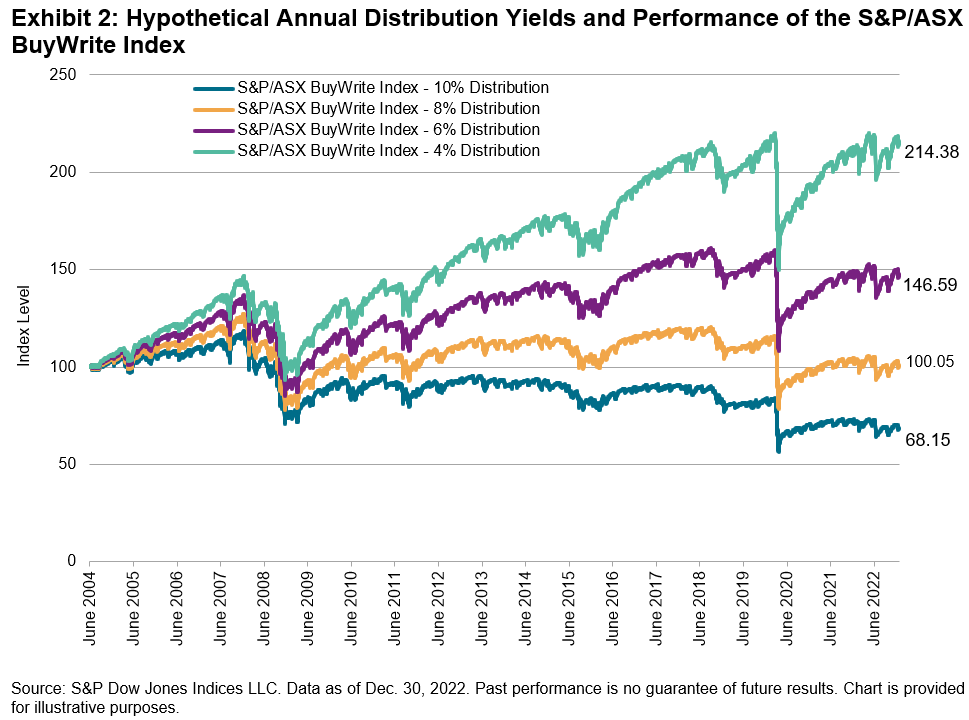

The premiums and dividends generated by the S&P/ASX BuyWrite Index are reinvested into the long equity position—the underlying S&P/ASX 200. In a hypothetical scenario in which the premiums and dividends are distributed instead of reinvested, the index would have been able to achieve an annual distribution yield of 8% across its 18-year history without losing its initial principal value (see Exhibit 2). This represents a potentially valuable source of income.

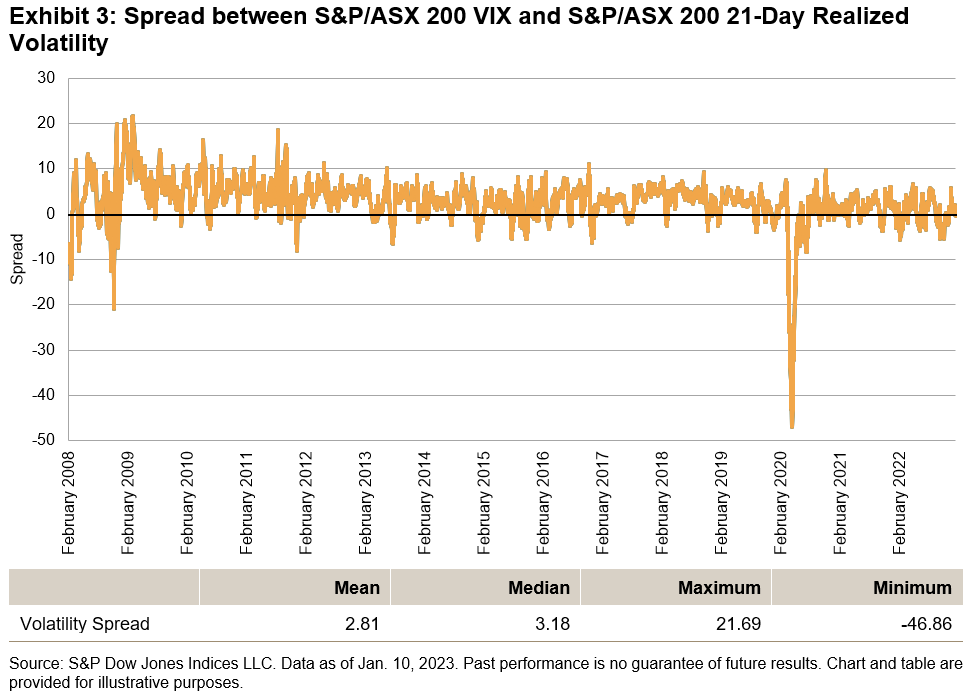

Theoretically, the income-generating feature of this type of strategy is associated with the spread between implied and realized volatility. Implied volatility can be defined as the market’s prediction of an asset’s future volatility, while realized volatility represents the volatility that actually occurred. The S&P/ASX BuyWrite Index is able to capture the risk premium that arises from the discrepancies between these two measures of volatility. In general, a covered call strategy pays off when the implied volatility of the index—as measured here by the S&P/ASX 200 VIX—is greater than its realized volatility. On average, this has been the case since 2008 (see Exhibit 3). Since implied volatility is one of the key factors in option pricing, a lower realized volatility allows option sellers to capture higher option prices—premiums—than the realized market conditions would have merited—this phenomenon is known as the volatility risk premium.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.