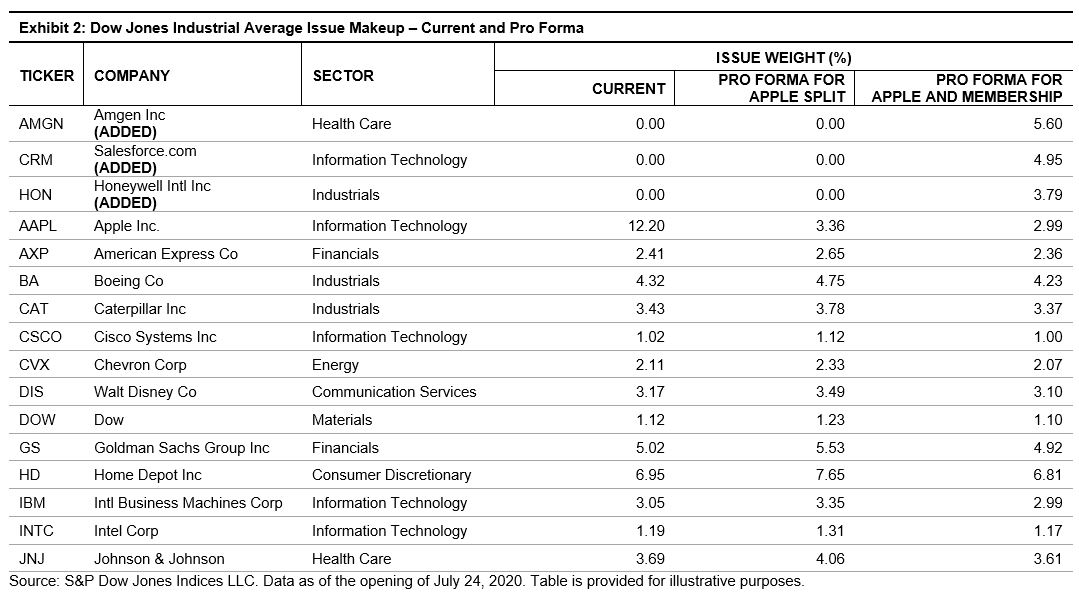

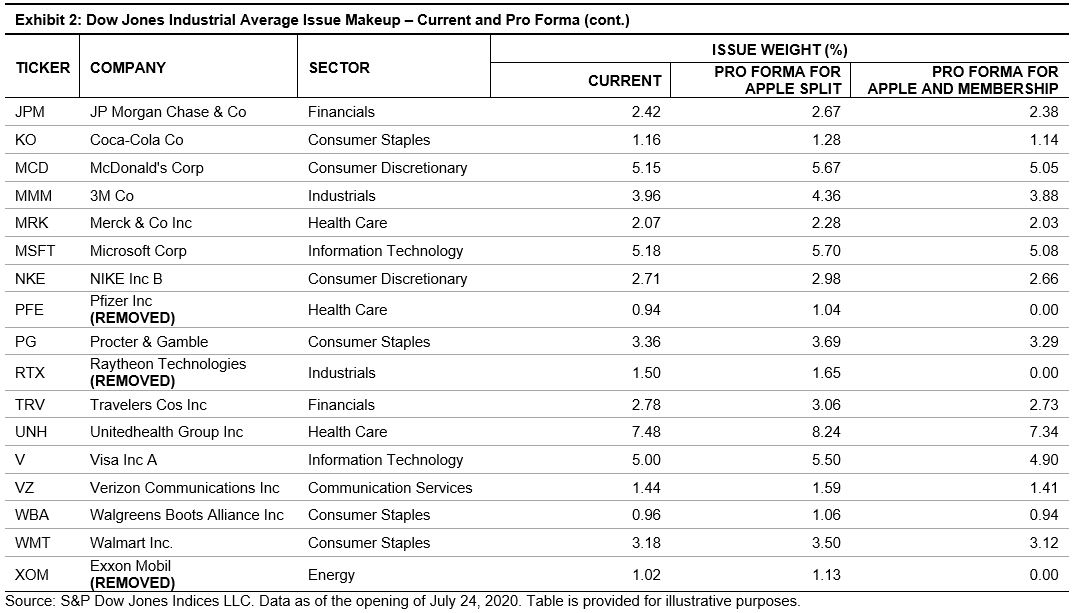

S&P Dow Jones Indices (S&P DJI) announced major changes to the 124-year-old Dow Jones Industrial Average® (The Dow®), effective on the same day (Aug. 31, 2020) as Apple’s (AAPL) four-for-one stock split. Specifically, Salesforce.com (CRM) will replace Exxon Mobil (XOM), Amgen (AMGN) will replace Pfizer (PFE), and Honeywell International (HON) will replace Raytheon Technologies (RTX).

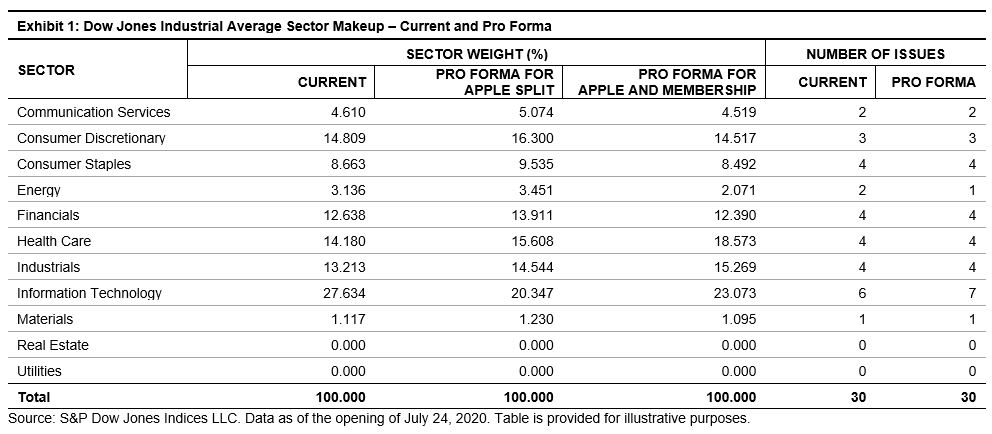

Issue reviews are constant in The Dow, with any change having its own investment rationale and impact. However, last month, Apple, the largest-weighted issue in the index, announced a four-for-one stock split, which would effectively change its weight in The Dow from 12.20% to 3.36%, increasing the weight of the other 29 members by 10.1% each and reducing the weight of the Information Technology sector from 27.63% to 20.35%. This action was a catalyst for the changes S&P DJI made, as it continues to align the index with the shifting nature of the U.S. economy.

The most notable change was the removal of Exxon Mobil, which was added to The Dow in 1928 as Standard Oil of New Jersey, when The Dow increased its membership from 20 to the current 30. The Energy sector has been experiencing a shrinking footprint in the marketplace. Exxon Mobil’s removal will leave Chevron (CVX; added to the Dow in 1924 as Standard Oil of California) representing the sector, with a weight of 2.07% (pre-changes, the two had a weight of 3.14%). The addition of Salesforce.com will help diversify the Information Technology exposure to application software and will make up for some of the reduction in weighting due to the Apple split (from 27.63% down to 20.35% for the split, then up to 23.07% after the membership changes).

Pfizer was the lowest-priced issue in the index (and therefore had the lowest weighting) and is planning to spin off its generic drug business, which would reduce its price and weight. Amgen is one of the largest issues in the biotechnology field and is seen as broadening The Dow’s exposure to Health Care (currently 14.2% and 18.6% after the changes).

United Technologies (UTX) completed its spin-off of Carrier (CARR) and Otis Worldwide (OTIS), which were added to the S&P 500®, and merged with Raytheon (RTN) to form Raytheon Technologies, which is concentrated in the Aerospace and Defense (A&D) industry. Given Boeing’s (BA) representation in the A&D area, Honeywell International (which was originally Allied Chemical and was added to The Dow in 1925 and removed in 2008) was seen as diversifying the Industrials sector.

The bottom line is that the marketplace is always changing, and market barometers need to change with it. Each of the changes reflects the environmental changes of the economy and is not intended as a buy-sell indicator, but as a “that’s the way it is” reflection of the market.

As a brief review, index modifications to the

As a brief review, index modifications to the