COVID-19 driven volatility has caused market participants to refocus on defensive strategies. As investors turned to quality, the S&P 500® Quality Index demonstrated better downside protection and outperformed. Furthermore, it offered a sizable dividend yield of 2.2%. This analysis investigates attributes of the index.

Breaking Down Components

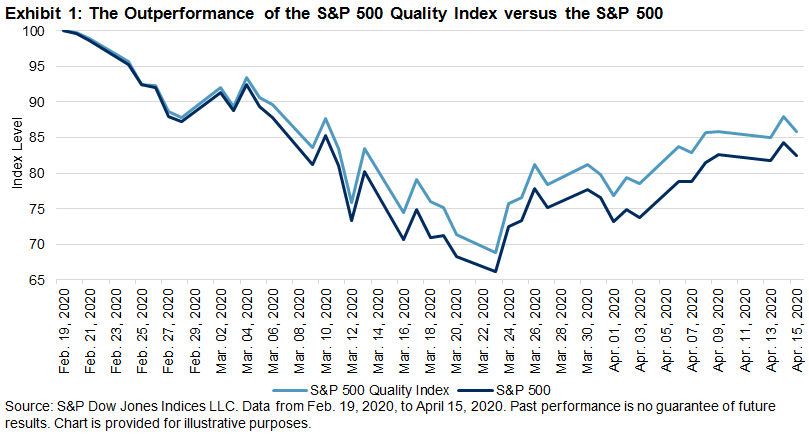

From all-time highs on Feb. 19, 2020, to April 15, 2020, the S&P 500 dropped about 18%. In contrast, the S&P 500 Quality Index outperformed its benchmark by 3.3% (see Exhibit 1).

The S&P Quality Index Series uses three components to define constituents’ overall quality scores:

- Balance sheet accruals ratio (BSA),

- Return on equity (ROE); and

- Financial leverage ratio (leverage).[1]

In Exhibit 2, we dissect the index’s performance into three components: BSA, leverage, and ROE attributions.[2] As seen in Exhibit 2, BSA had the highest contribution to the outperformance, followed by ROE.

ROE and leverage are commonly used metrics. Market participants also generally use earnings quality or growth. The S&P 500 Quality Index uses BSA to capture earnings quality[3] instead of earnings variability (EV),[4] another popular measure to capture earnings growth. Recently, investors have been more focused on earnings quality than growth,[5] resulting in BSA outperforming EV (see Exhibit 3).

Besides its outperformance, the S&P 500 Quality Index also yielded about 2.2%. This level was second only to the S&P 500 Bond Index (see Exhibit 4).

In conclusion, the S&P 500 Quality Index showed its defensive characteristics during this uncertain period. In addition, with a 2.2% dividend yield, it also provided income for investors, especially when 10-year U.S. Treasuries were yielding close to zero.

[1] The detailed factor definition and index construction are laid out in the S&P Quality Indices Methodology.

[2] S&P 500 Quality BSA Attribution: Securities in the eligible universe are selected for index inclusion based on their accruals ratio z-score determined during the semiannual rebalancing of the S&P 500 Quality Index. The values for all securities are ranked in ascending order.

S&P 500 Quality Leverage Attribution: Securities in the eligible universe are selected for index inclusion based on their financial leverage ratio z-score determined during the semiannual rebalancing of the S&P 500 Quality Index. The values for all securities are ranked in ascending order.

S&P 500 Quality ROE Attribution: Securities in the eligible universe are selected for index inclusion based on their return-on-equity z-score determined during the semiannual rebalancing of the S&P 500 Quality Index. The values for all securities are ranked in ascending order.

[3] Richardson, Sloan, Soliman, and Tuna, Accrual Reliability, Earnings Persistence and Stock Prices, Journal of Accounting & Economics, Vol. 39, No. 3, 2005.

[4] EV is usually calculated as the standard deviation of year-over-year earnings per share growth over (n-) number of previous fiscal years.

[5] We selected the top quintile (Q1) of EV factor to form a cap-weighted hypothetical portfolio using the S&P 500 as the underlying universe. The higher the EV, the less stable the earnings growth. For details, please refer to https://www.indexologyblog.com/2018/10/01/measuring-earnings-quality-balance-sheet-accruals-ratio-versus-earnings-variability/.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.