The balance sheet accruals ratio (BSA)[1] is widely used in the investment community to measure earnings quality.[2] This is in part due to accruals being perceived as transient and subject to considerable estimations, manipulations, and potential misrepresentations.[3]

BSA is one of the three quality metrics used in the S&P Quality Index Series. We define BSA as the change of a company’s net operating assets over the previous year, divided by its average net operating assets over the last two years. All else equal, the higher the BSA, the lower the company’s earnings quality.

Similarly, some market participants use historical earnings variability (EV) to measure the stability of earning. EV is usually calculated as the standard deviation of year-over-year earnings per share growth over (n-) number of previous fiscal years. The higher the EV, the less stable the earnings growth.

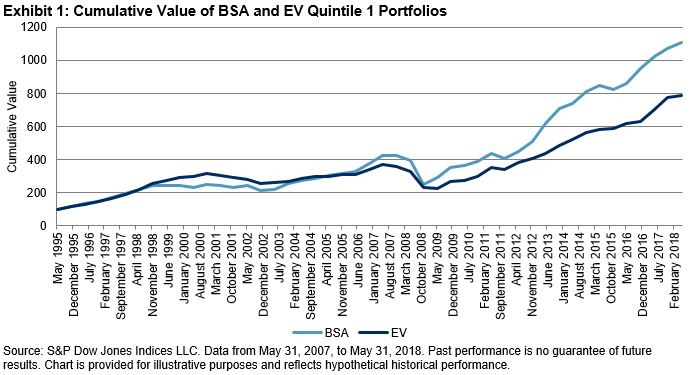

Given that there are various ways of defining and capturing earnings, it is worthwhile to dive deeper into the long-term performance of BSA and EV to understand their return patterns. Using the S&P 500® as our underlying universe, we rank securities in an ascending order based on BSA and EV separately, and divide them into quintiles.

We then select the top quintile (Q1) of each factor to form a cap-weighted hypothetical portfolio. For consistency purposes, we follow the S&P 500 Quality Index rebalancing frequency and rebalance the hypothetical quintile portfolios on a semiannual basis. Thus, the performance of these two factors is based on six-month forward returns.

To avoid survivorship bias, we include companies that currently are and historically have been in the benchmark in an attempt to ensure that the back-tested results will not suffer from survivorship bias. Compustat is the main data source for company-level fundamental data. To prevent look-ahead bias, the fundamental data is lagged by 45 days. We use the S&P DJI stock-level total return data (including both dividend and price return) from May 31, 1995, to May 31, 2018.

Exhibit 1 shows the cumulative values of the BSA and the EV quintile 1 portfolios over the whole back-tested period, assuming starting value of 100 on May 31, 1995. From May 31, 1995, to May 31, 2018, the cumulative returns of the BSA Q1 portfolio exceeded that of the EV Q1 portfolio. However, we can also see that there are periods when the BSA Q1 portfolio underperformed the EV Q1 portfolio.

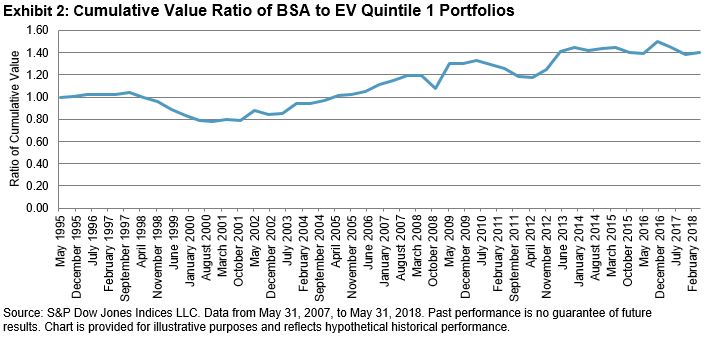

Exhibit 2 shows the ratio of BSA quintile 1 portfolio to EV quintile 1 portfolio values. The ratio below 1 indicates that BSA underperformed during the period.

The BSA Q1 portfolio noticeably underperformed the EV Q1 portfolio during the tech bubble period, starting from the second half of 1999 to early 2000, with the BSA to EV performance ratio dipping from 1 to 0.79. The findings are not surprising, given that investors blindly chased earnings growth and ignored earnings quality during that period. The tech bubble burst made market participants consider the importance of earnings quality. The BSA Q1 portfolio started to outperform afterward.

After BSA’s extended outperformance over EV, BSA began to underperform in 2017, as markets focused more on earnings growth. However, if history is any indication, when there is an earnings quality event, market participants should consider turning their attention toward factors that aim to capture earnings quality.

[1] Sloan, Do Stock Prices Fully Reflect Information in Accruals and Cash Flows About Future Earnings? The Accounting Review, Vol. 71, No. 3, 1996.

[2] Richardson, Sloan, Soliman and Tuna, Accrual Reliability, Earnings Persistence and Stock Prices, Journal of Accounting & Economics, Vol. 39, No. 3, 2005.

[3] Ung, Luk and Kang, Quality: A Distinct Equity Factor? S&P Dow Jones Indices Research Report, 2014.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.