Our Year-End 2018 Canada SPIVA scorecard was released today. In addition to showing that the majority of Canadian active equity managers failed to outperform their benchmarks, the scorecard’s results provide the opportunity to dispel some common misconceptions. Here is a brief summary.

1) Higher volatility does not necessarily result in outperformance by active managers

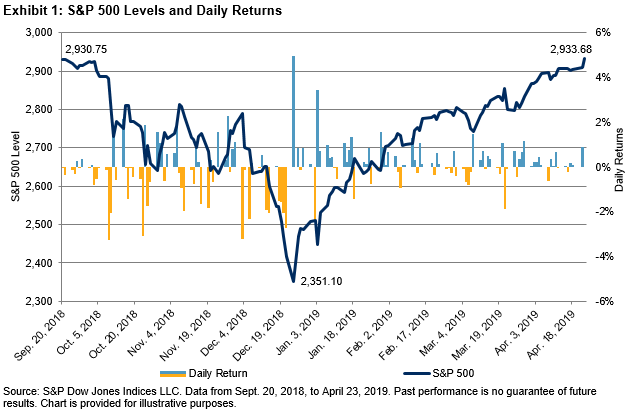

A common view among market participants is that more volatile markets favor active management over passive solutions. However, in a year when Canadian equities were caught up in global equity gyrations, 75% of Canadian active equity managers underperformed in 2018, as the majority of funds lagged in all categories.

Such underperformance by active managers in more volatile environments is consistent with other international regions, and perhaps speaks to a bias many active managers have for higher-beta stocks. Indeed, these stocks are expected to be more heavily impacted by market corrections.

2) Smaller-cap stocks may not be better suited to active management

Another popular perception is that small- and mid-cap stocks are inefficient asset classes that are more suited to active management. However, 80% of all small- and mid-cap managers failed to beat the S&P/TSX Completion (-12.85%) in 2018, suggesting they struggled to navigate the market turbulence as the equity benchmark recorded its worst calendar-year performance in a decade.

In fact, only once in the last eight calendar-year periods did the majority of small- and mid-cap managers beat the S&P/TSX Completion. Hence, using an index-based approach to access smaller Canadian companies would have been beneficial, historically.

3) Get what you pay for? Not necessarily!

In many walks of life we are told that the cost of something is proportional to its quality. But while some investors may believe higher-fee funds are illustrative of higher quality managers – as measured by their ability to outperform benchmarks – the data does not reflect this.

Exhibit 3 shows the relative performance of surviving active mutual funds in 2018. Funds in each category are first grouped according to their expense ratio from the end of December 2017: “Q1” contains the 25% of funds in each category with the lowest expense ratio, while “Q4” contains the 25% of funds in each category with the highest expense ratio. The average relative return in 2018 is then taken for each group; a negative number indicates the benchmark outperformed.

Quite clearly, higher expense ratios were typically associated with a greater degree of underperformance compared to their benchmarks. Hence, market participants may find it useful to consider the impact of fees in determining relative performance.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.