After a strong January 2018, the U.S. equity market started February with a roller coaster ride. The CBOE Volatility Index® (VIX®), which has been relatively quiet over the past couple years, spiked up and crossed the 50 mark intraday on Feb. 5, 2018. On the same day, the S&P 500® VIX Short Term Futures Inverse Daily Index and its linked exchange-traded products (ETPs) lost more than 90% in value. In light of this significant drop, it is worthwhile to review the mechanics of an inverse volatility index, and how the index value is established. In this two-part blog, we examine factors potentially contributing to the recent spike in volatility and significant negative performance in the S&P 500 VIX Short Term Futures Inverse Daily Index. In this first part of the blog series, we demonstrate that an inverse volatility index is not a “true short” of the underlying reference index.

An Inverse Index Is Not a “True Short”

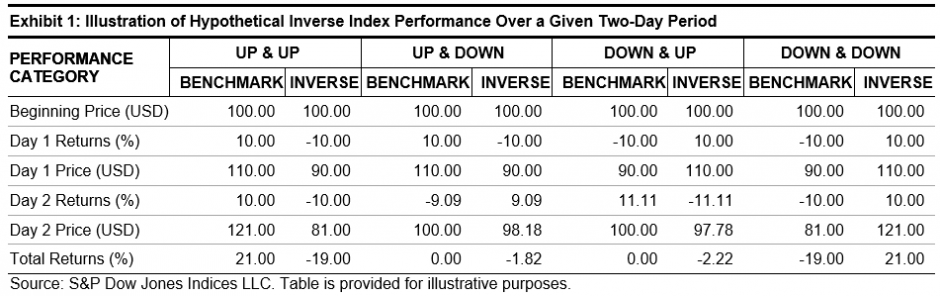

Before we look into the S&P 500 VIX Short Term Futures Inverse Daily Index, we need to understand that an inverse index is designed to provide daily inverse return to a benchmark. In other words, an inverse index is designed to deliver the opposite of the performance of the benchmark on a daily basis. Its performance over longer periods of time can differ significantly from the “true short” of the underlying benchmark during the same period of time. This effect can be magnified in volatile markets.

Exhibit 1 illustrates the performance of a hypothetical benchmark index and its inverse over a two-day period. As the examples demonstrate, an inverse index that is set up to deliver the inverse of the performance of a benchmark every day will not necessarily achieve that goal over weeks, months, or years due to the compounding effect. If the benchmark index moves around a lot and then ends up in the same place, an inverse index will lose value while a “true short” would not. However, an inverse index does not always underperform. If the benchmark index is trending down, an inverse index can possibly deliver better performance than -1x cumulative performance.

Due to the power of compounding as illustrated in Exhibit 1 and the low volatility regime we have had in the past a couple of years, the S&P 500 VIX Short Term Futures Inverse Daily Index has outperformed the “true short” of its benchmark, the S&P 500 VIX Short-Term Futures Index. In 2017 alone, the S&P VIX Short Term Futures Inverse Daily Index returned 186%, while the S&P VIX Short-Term Futures Index lost 72%. The underlying mechanism for an inverse index (not limited to this example) to achieve this outperformance over a “true short” is to increase its position while it’s rising and decrease its position while it’s dropping. In the case of the S&P VIX Short Term Futures Inverse Daily Index, this would theoretically translate to increasing the number of VIX futures to short, while its benchmark is dropping. Given that each VIX futures contract has a constant vega exposure of 1000, the S&P VIX Short Term Futures Inverse Daily Index has been gradually increasing its vega exposure over the past couple of years. Many market participants may not necessarily be aware of the jump in the vega exposure of the ETPs linked to this index. The size of the index-linked, short-volatility ETP market (which stood around USD 2.7 billion at the peak[1]) may call for even more hedging in light of this increased vega exposure should another VIX jump happen.

In the next blog, we will analyze how the mechanics of a VIX futures index, as well as hedging by market participants, may have contributed to the Feb. 5, 2018, after-hour spike of VIX futures.

[1] Source: Bloomberg.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.