2017 was a great year for shorting VIX futures strategies. The S&P 500® VIX Short-Term Futures Inverse Daily Index returned 186.39%.

Selling volatility does not rely on interest rates or dividends. Historically, investors have been selling options to generate income. Compared to selling equity options, selling VIX futures is an operationally simple strategy that can provide clean volatility exposure through exchange-traded liquid instruments. However, market participants should keep in mind the extra risk they are taking and the potential for sharply negative returns because of the mechanics of the VIX futures curve.

The VIX futures curve is in contango about 80% of the time, which creates the insurance-like premium that is paid by a long position and received by a short position. In a stressed market, the term structure can invert and create a negative roll return for the short position. This indicates the potential to capture significant returns over long horizons with infrequent sharp losses through a short VIX futures position.

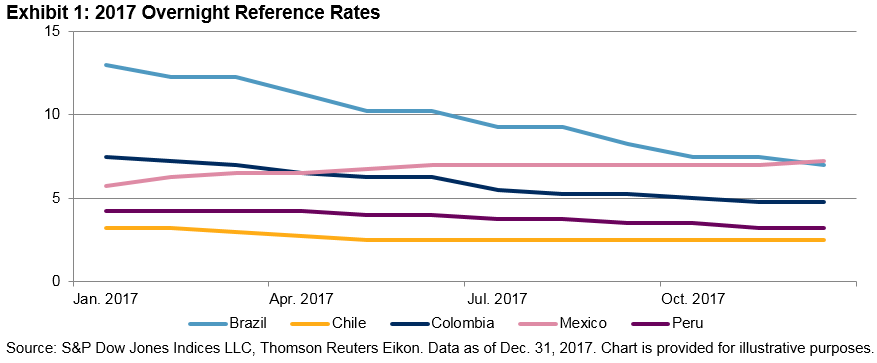

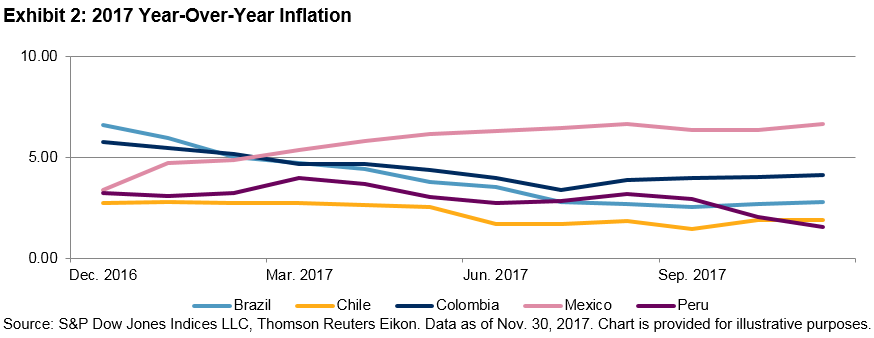

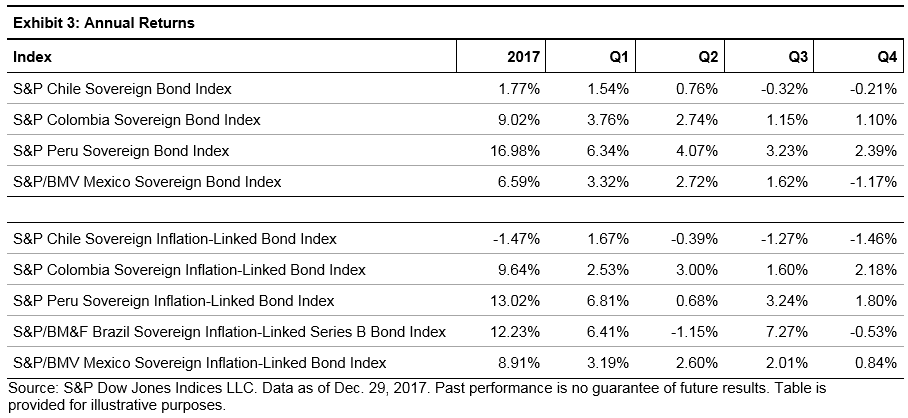

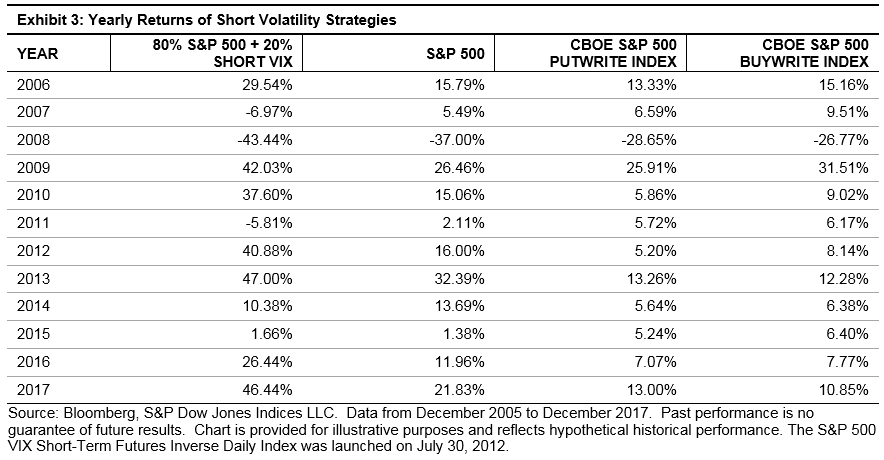

To illustrate the pros and cons of short VIX futures strategies, we constructed a hypothetical, monthly rebalanced portfolio that allocates 80% to the S&P 500 and 20% to the S&P 500 VIX Short-Term Futures Inverse Daily Index. We then compared its performance to a pure equity portfolio and two popular option writing strategies, represented by the CBOE S&P 500 BuyWrite Index and the CBOE S&P 500 PutWrite Index, respectively. The results (from December 2005 to December 2017) are shown in Exhibits 1, 2, and 3.

These exhibits show that selling VIX futures had a completely different impact than selling equity options on an equity portfolio in the back test period.

- Selling VIX futures increased both annualized return and volatility, while writing put or call options tended to reduce portfolio volatility by forgoing part of the returns.

- Despite its increased drawdown, shorting VIX futures significantly improved the long-term returns of the portfolio.

- Risk-adjusted returns, as measured by return per unit of volatility, were comparable in all four portfolios.

Unlike a buy-write strategy that sells a covered call, shorting VIX futures tended to perform the best in a bull market and suffer the most in a bear market. This is because shorting VIX is selling volatilities across all strikes, and it is essentially longing the equity market due to the negative correlation between VIX (both the spot and the futures) and the equities. In contrast, a buy-write strategy limits the upside potential of the equity market and incurs a performance drag in a strong bull market. The option premium received, however, mitigates the loss and the buy-write index generally outperforms when the market goes down.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.