Dividend investing is an ever popular topic across different markets. Market participants have been using ETFs to implement various dividend strategies for more than a decade. The first dividend ETF, the iShares Select Dividend, was launched in 2003. Nevertheless, dividend ETPs have experienced tremendous growth in assets since year-end 2009. As of June 30, 2017, the total assets of purely dividend screened or weighted ETPs reached USD 178.6 billion, with a compound annual growth rate of 35.5% since year-end 2009 (see Exhibit 1).

Despite rising AUM in the low/minimum volatility and multi-factor ETPs in the past two years, dividend ETPs have remained the leading category of strategic-beta ETPs by assets across many regions and countries.[1] In the first three quarters of 2017, dividend ETPs dominated the inflows among various types of smart beta ETPs.[2]

The most cited growth driver for dividend investing is the global low-yield investment environment seen in recent years. As shown in Exhibit 3, the growth of dividend ETPs’ assets since year-end 2009 coincided with a period of low and declining 10-year government bond yields in the U.S., eurozone, and Japan.

Another underlying and probably longer-term driver for the growth of dividend investing is the demographic change in high income regions, such as the U.S., European Union, and Japan (see Exhibit 4). As more market participants move gradually from the consolidation to the decumulation stage of their investment lifecycles, dividend strategies can become an attractive investment option for providing stable cash flows.

Among various types of income ETPs listed in the U.S., high-dividend equity ETPs recorded the highest five-year absolute and risk-adjusted return as of Aug. 31, 2017, although they had lower yield than a few other income asset classes. Compared to other equity income products, such as REITs and MLP ETPs, high-dividend equity ETPs tend to have less sector concentration risk and lower price volatility. Despite the rate hikes since December 2015, U.S. interest rates remain low and high-yield ETPs, which offer yield premium, remain attractive to income-seeking market participants.

[1] A Global Guide to Strategic-Beta Exchange-Traded Products (September 2016 and September 2017). Morningstar Manager Research.

[2] Blackrock Global ETP Landscape September 2017 Report.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.

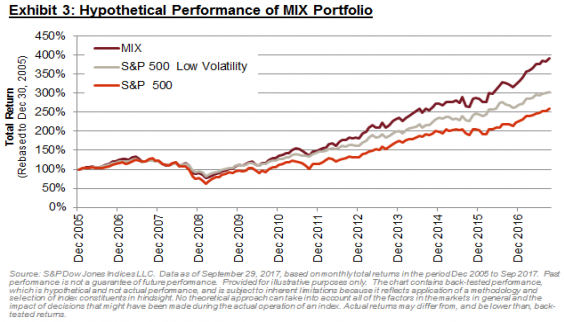

On a hypothetical basis, the MIX portfolio achieved roughly 100% upside capture (i.e. it did not lag in bull markets), while retaining a considerable degree of protection (77% downside capture). The MIX portfolio also demonstrated favourable performance statistics over longer periods. Over all possible rolling 12-month periods during our study, Low Volatility outperformed around 59% of the time; this increases to 72% for the MIX portfolio (Exhibit 5).

On a hypothetical basis, the MIX portfolio achieved roughly 100% upside capture (i.e. it did not lag in bull markets), while retaining a considerable degree of protection (77% downside capture). The MIX portfolio also demonstrated favourable performance statistics over longer periods. Over all possible rolling 12-month periods during our study, Low Volatility outperformed around 59% of the time; this increases to 72% for the MIX portfolio (Exhibit 5). The

The