“Weighing In:” will be a series of posts comparing and contrasting the impact of different weighting schemes within commodity indices. The series will be the first to feature our two headline indices, the equally weighted Dow Jones Commodity Index (DJCI) and the world production weighted S&P GSCI. The purpose of the series is to help you reach your portfolio goals by understanding the effect of weighting inside commodity indices. We will kick off with a description of the difference between the two major weighting schemes, and in subsequent discussions will analyze the historical behaviors of each of the indices.

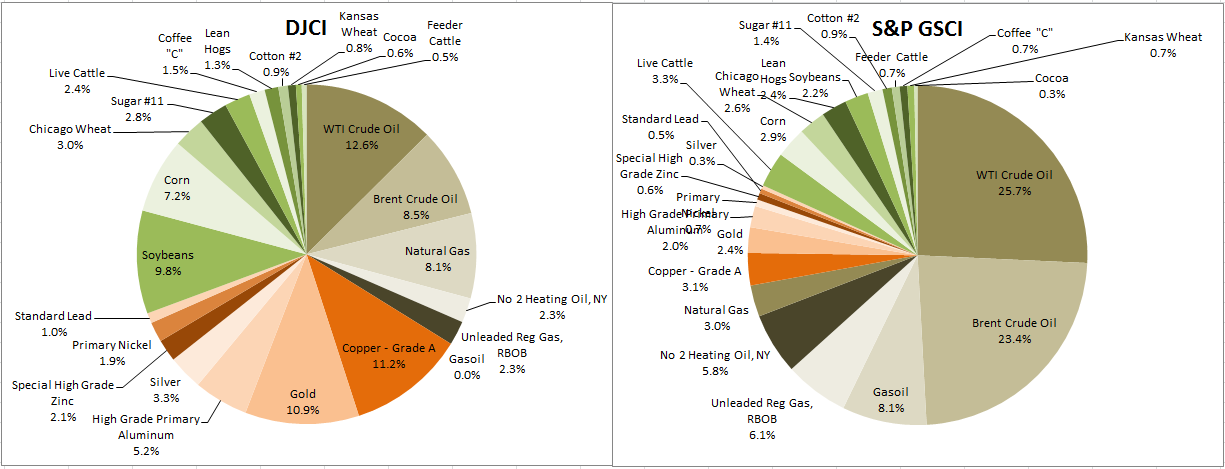

Both the DJCI and S&P GSCI have the same methodologies with the exception of the weighting schemes and the rebalance periods back to their respective target weights. The resulting index compositions differ dramatically. See below for a comparative snapshot of weights as of July 9, 2014:

Notice the significant difference in the weights, especially in energy where the DJCI has 33.8% and the S&P GSCI has an energy weight of 72.1%. Also notice the relatively low weight in the S&P GSCI of metals at 9.6% versus 35.5% in the DJCI, and lower agriculture and livestock weight 18.2% in the S&P GSCI versus 30.7% weight in the DJCI.

Why is this?

Again, It is from the different weighting methods between the indices. The DJCI is an equally weighted index where step one is to liquidity weight each commodity by a 5 year average of total dollar value traded. Next the commodities are grouped into components by their physical similarities and correlations to apply caps to further diversify. The caps are applied so that no more than one component is greater than 32% and no subsequent component is greater than 17%. This is done in an interative process until the requirement is filled. Last the sectors are limited to 33% each and this is rebalanced quarterly. The goal is to incorporate diversification and liquidity as the intrinsic characteristics of the index.

The S&P GSCI is a world production weighted index where the goal is to reflect the relative significance of each of the constituent commodities to the world economy, while preserving the tradability of the index by limiting eligible contracts to those with adequate liquidity.

With respect to each Designated Contract, a Contract Production Weight (CPW) is calculated based on world production and trading volume. The final CPWs are rounded to seven digits of precision.

The calculation of the CPWs of the Designated Contracts involves a four-step process: (1) determination of the World Production Quantity (WPQ) of each S&P GSCI Commodity, (2) determination of the World Production Average (WPA) of each S&P GSCI Commodity over the WPQ Period, (3) calculation of the CPW based on the Contract’s percentage of the relevant Total Quantity Traded (TQT), and (4) certain adjustments to the CPWs.

World Production Quantity (WPQ)

The WPQ of each S&P GSCI Commodity is equal to the total world production of the S&P GSCI Commodity over the WPQ Period.

The use of the five-year WPQ Period (and the averaging of that five-year period to determine the WPAs) is intended to mitigate the effect of any aberrational years with respect to the production of a particular commodity. For example, if a given commodity is produced primarily in one part of the world that suffers damage from hurricanes or earthquakes in a particular year, resulting in curtailed production levels, the use of that year’s production figures might not accurately reflect the significance of the commodity to the world economy. Commodity production in a particular year may also be higher or lower than would normally be the case as a result of general production cycles, supply and demand cycles, or worldwide economic conditions. Measuring production levels over a five-year period should generally smooth out any such aberrational years.

The definition of the WPQ Period imposes a delay of approximately one-and-one-half (1 ½) years between the end of the WPQ Period and the end of the relevant Annual Calculation Period. This delay is because world production statistics are often incomplete and subject to revision after their original publication. Imposing a delay on the WPQ Period generally enhances their accuracy and reliability.

The WPQ Period is defined as the most recent five-year period for which complete world production data is available for all S&P GSCI Commodities from sources determined by S&P Indices to be reasonably accurate and reliable. This procedure is intended to assure that the same WPQ Period is used for all S&P GSCI Commodities, which allows comparisons between production figures to be made without taking into account temporary aberrations in different time periods.

World Production Average (WPA)

The WPA is simply the average annual production amount of the S&P GSCI Commodity based on the WPQ over a five-year period.

Contract Production Weight (CPW)

In calculating the CPW of each Designated Contract on a particular S&P GSCI Commodity, the WPA of such Commodity is allocated to those Designated Contracts that can best support liquidity.

With respect to each Designated Contract, the CPW is equal to the Percentage TQT for such Contract multiplied by the WPA of the underlying S&P GSCI Commodity (after any necessary conversion made for purposes of the calculation) and divided by 1,000,000.

The simpler of the two is the equally weighted DJCI. However, both indices are used as asset class representations in order to fulfill different portfolio goals. The most popular reasons investors use commodity indices are for diversification and inflation protection, so we will evaluate the historical effectiveness of both indices in these roles. Additionally, we may explore how well each of the indices fills requirements of other motivations behind commodity allocations such as liquidity, emerging markets exposure, or hedging against rising interest rates.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.