It’s a little late for an Easter post but this saying is about one of the key investment principles, diversification. Simply put, diversification happens when assets inside your portfolio move in opposite directions. The investment measure of diversification is correlation and it can range from -1.0 to +1.0. If correlation is -1.0 between two assets, then they have moved exactly opposite each other; conversely, if the correlation is +1.0, then they move exactly together. Correlation of -1.0 is the holy grail of diversification to produce a more efficient portfolio – meaning for the same return, there is less risk, or for the same risk, there is higher return.

Commodities, which by definition of being the natural resources that are used to build society, are meaningfully different than financial assets like stocks and bonds. While they have been around since the beginning of time, most investors did not consider them a portfolio asset until about 10 years ago. They grew wildly popular with the institutional crowd as the major benchmark passed its 10-year track record, and with the advancement of ETFs, became popular (at least gold and oil) with retail investors. At least for the institutions, the main reason for the attractiveness of the asset class was diversification.

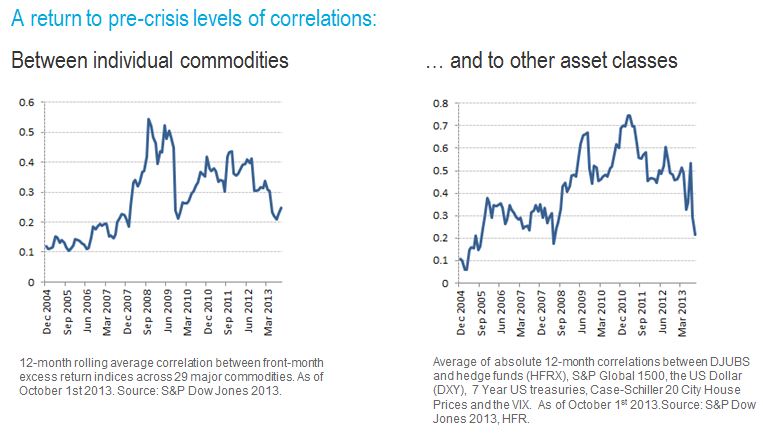

Unfortunately for many, the diversification investors hoped for from their allocations to commodities fell flat as the correlation between commodities and commodities to other asset classes rose to almost 0.8 post the financial crisis.

There are two main reasons this happened:

1. The inventories were built up starting in the late 90’s to very high levels by 2005. Then the financial crisis hit, demand dropped and supply shocks (like the weather, war or pipeline bursts) lost their impact. This source of return from supply shocks or surprises, called expectational variance, that drives return patterns of commodities to be different from each other (gas to corn to gold) and to be different than other asset classes like stocks and bonds disappeared in the sea of excess inventory after the crisis.

2. The unprecedented quantitative easing caused a risk-on/risk-off environment where either the stimulus worked or didn’t work. If a commodity investor did not feel the insurance risk premium was high enough to supply to the producer, no investment was made. Without the supply of insurance, the incentive for producers diminished and the volatility of prices increased. This proved too much risk for the investors to bear that drove the game of risk transfer back to the producers. Now, not only is backwardation back from the diminished inventories, but the result of that in conjunction with the tapering of quantitative easing, is that diversification is back.

Notice in the charts above that both correlation of commodities to each other and to other asset classes has fallen to precrisis levels of about 0.2, indicating little movement together with stocks and bonds and little movement together with each other. This makes commodities, once again, an asset class to provide diversification, and institutional investors are taking notice.

Notice in the charts above that both correlation of commodities to each other and to other asset classes has fallen to precrisis levels of about 0.2, indicating little movement together with stocks and bonds and little movement together with each other. This makes commodities, once again, an asset class to provide diversification, and institutional investors are taking notice.

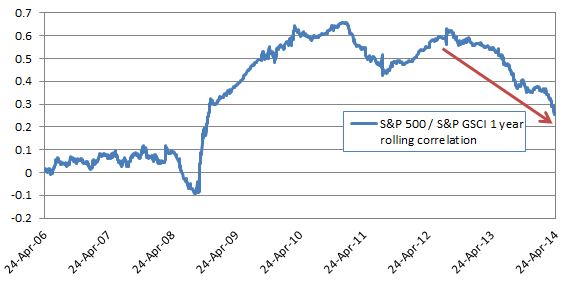

Last, the key question is… Will this diversification continue?

Based on the correlation patterns of the S&P 500 to the S&P GSCI, there is a compelling case this will continue.

The 12 month correlation between the S&P 500 and S&P GSCI at 0.26 is lower than at any point since November 2008 and heading down fast. Shorter term measures such as the 90 day and 30 day correlation are even lower at 0.17 and 0.01, suggesting that as correlation “catches up” with the history, it will head down further.

Special thanks to my colleague, Timothy Edwards, who helped with this.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.