The history of active investment management is, for the most part, a history of failure and frustration. Most active managers underperform most of the time, and success in one period seems not to predict subsequent success. We have long argued that active underperformance is not coincidental—it happens for identifiable and understandable reasons, and is therefore likely to continue.

But—most of the time is not all of the time, and most active managers are not all active managers. Some market environments may be more conducive to relatively favorable (or, to be precise, relatively less unfavorable) active performance. As I write in mid-December, 2021 is far enough advanced for us to attempt some informed speculation about what SPIVA® will reveal when the final results are in.

There are both positive and negative signals about the prospects for active management:

- One of the most consistent challenges for active managers arises because, in most years, most stocks in the S&P 500® underperform the index. Returns are typically driven by a relatively small number of strong performers, which pull the index’s return above that of most of its constituents. Through the end of November, this was precisely the situation in the S&P 500: the index was up 23%, versus a gain of only 19% for the median stock. Only 42% of index members outperformed through the first 11 months of the year. Needless to say, fewer outperformers make for more challenging stock selection.

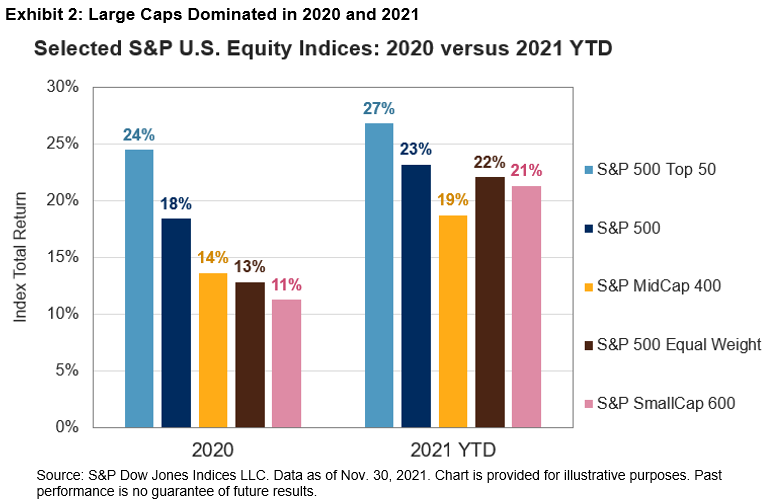

- Strong markets historically have been somewhat more challenging for active managers; this is particularly true when the strong market is driven by some of the index’s largest names. Exhibit 2 shows us that the largest 50 stocks in the S&P 500 are comfortably in the lead for 2021. While it’s relatively difficult for active managers to overweight the largest names in their benchmark index, the reverse is not true. In fact we’ve found that large-cap managers tend to do better in periods when the superior performance of mid- or small-cap names gives them a chance to “cheat” (I use the term lovingly) down the cap scale. Not this year—although the performance of larger names may give mid- and small-cap managers an edge.

- On the other hand: SPIVA data suggest that most active managers typically underweight lower volatility, low beta stocks; when Low Volatility underperforms, or High Beta outperforms, active results tend to improve. Through November 30, the S&P 500 Low Volatility Index was up 13% for the year, while the S&P 500 High Beta Index had risen 36%. The gap has narrowed in December, but so far this signal augurs well for active managers.

- Dispersion began the year at a relatively modest level, but has recently begun a noticeable rise, closing November well into the top quartile of its historical range. Although dispersion tells us relatively little about the success of active managers as a group, heightened dispersion suggests that the range of active outcomes will be greater than usual. The best active performers should shine, as the value of stock selection skill rises when dispersion is high.

Readers can form their own opinions about the proper balance of these observations. Recognizing the hazard intrinsic to all predictions, my guess is that when we draw a line under 2021, active underperformance, at least for large-cap U.S. managers, will persist.

Of course, the conditions that make active management more or less difficult can change. If, e.g., 2022 sees a declining market, with megacaps and lower volatility names leading the way down, it’s conceivable that active underperformance could become less prevalent. That may be cold comfort to the active management community and its customers—but sometimes cold comfort is all the comfort there is.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.