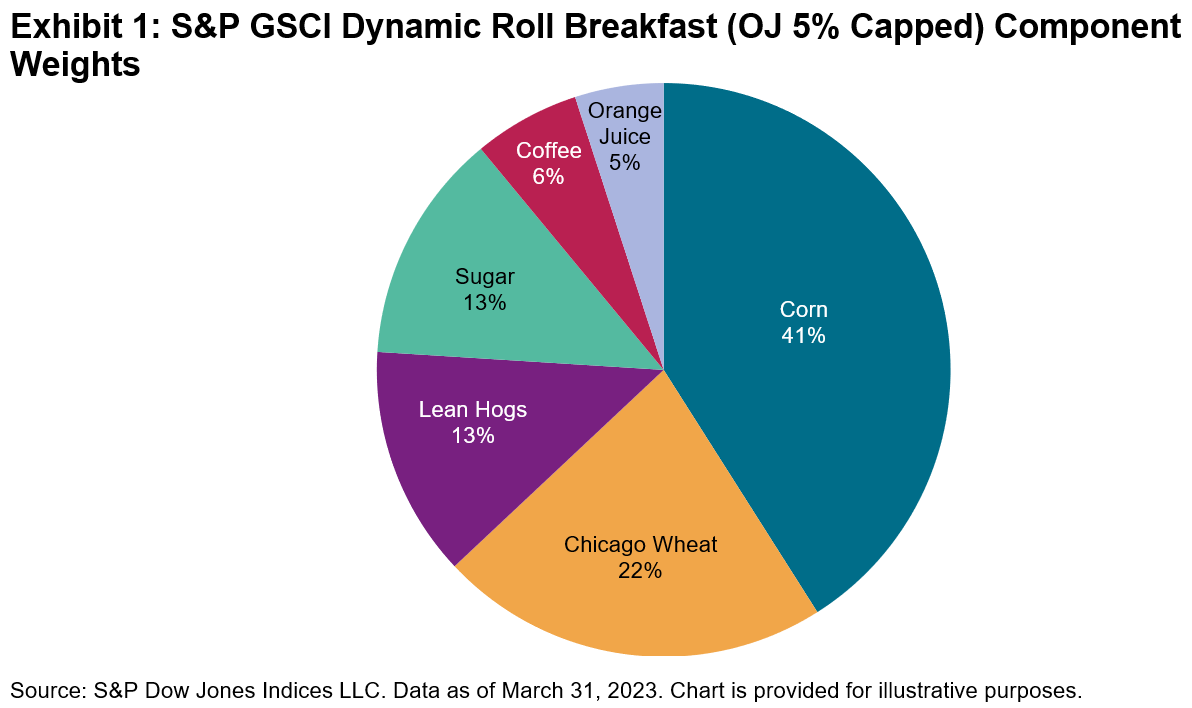

The first quarter of 2023 was a slow start to the year for commodities in general. The S&P GSCI Dynamic Roll Breakfast (OJ 5% Capped) also had a slow start, down 3.1%, after a solid 2022 performance of 14.12%. Maybe a higher weight to coffee would give the index the caffeine kick needed to boost performance—the S&P GSCI Coffee was up 5.8% for Q1 2023, as rising temperatures in the tropics lead to lower crop yields in the coffee-growing regions around the world. However, we would not be able to change the weightings of our breakfast index on a whim because it is based on world production of each of the six commodities making up the index.

The world’s food supply may continue to experience perilous geopolitical-based events like the Russia-Ukraine conflict, directly affecting nations who are some of the largest exporters of key grains, leading to price spikes like was seen last year with wheat. Other key agriculture-exporting regions are experiencing rising political instability, especially in some South American and North African countries.

While supply chain issues have mostly been resolved, the costs of production and transport will likely rise over time as every industry encounters scrutiny over carbon emissions. Major commodity producers regularly announce new plans to lower their carbon footprint, which will come at a higher cost but is needed to help combat climate change.

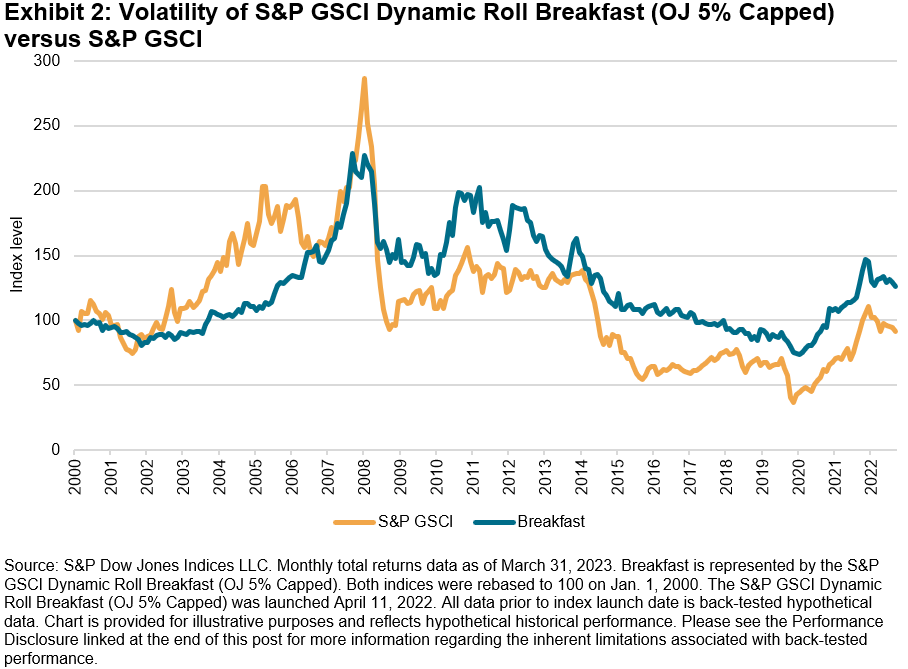

Compared to the headline benchmark S&P GSCI, breakfast commodities performed in a much less volatile manner over the last 20 years, as can be seen in Exhibit 2. The main reason is due to the lack of more volatile energy commodities that are included in the S&P GSCI. Unless gasoline is added to your morning coffee, breakfast tended to be a much smoother start to your day over the years, although there have been periods of much higher volatility for some of the individual breakfast commodities.

The S&P GSCI Dynamic Roll Breakfast (OJ 5% Capped) provides market participants with a new thematic way to look at commodities and offers a benchmark to key themes of food security against the backdrop of a rising global population. For more information on our commodities indices, please visit our website.