Firms with low credit risk generally have higher stock market returns than firms with high credit risk.1 The S&P 500® Higher Credit-Rating Ex Insurance Equity (HCREIE) Index is designed to capture the credit risk premium in the equity market. In this blog, we will introduce the index design, performance, and factor exposure.

Index Design

The S&P 500 HCREIE Index uses a company’s issuer credit rating (ICR)2 from up to three rating agencies—S&P Global Ratings, Moody’s, and Fitch—to select its constituents from the S&P 500 universe. To be eligible for index inclusion, a company’s long-term credit rating needs to be at or above ‘A-’/‘A3,’ from at least one rating agency.3

This index can be used by trusts, funds, or mandates seeking to invest in high quality assets. One example is Regulation 114 Trusts by reinsurers.4 The index requires that its constituents be U.S.-incorporated companies and excludes those classified by the Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS®) as insurance companies (GICS Code: 4030).

Once selected, index constituents are first weighted by float-adjusted market capitalization (FMC), then those FMC weights are adjusted so that the sector weights in the index equal the sector weights in the S&P 500. That is, the S&P 500 HCREIE Index is sector neutral relative to S&P 500.

Performance

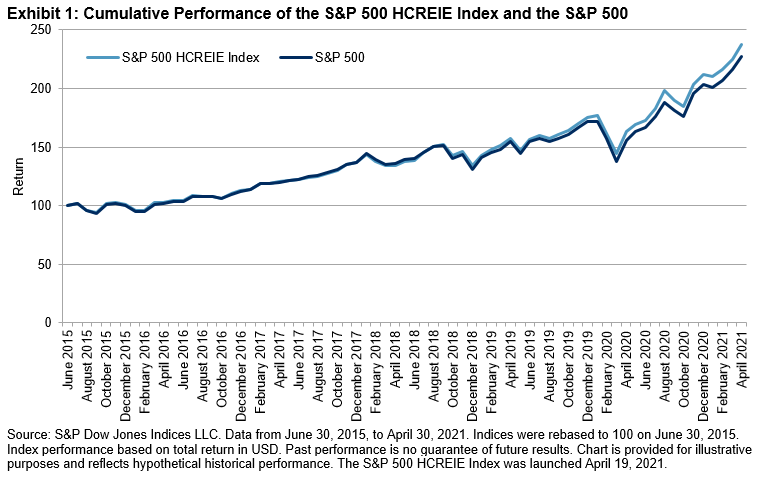

During the back-testing period from June 30, 2015, to April 30, 2021, the S&P HCREIE Index outperformed the S&P 500 by 10.22%. Rebasing the S&P 500 HCREIE Index and the S&P 500 to 100 on June 30, 2015, the S&P 500 HCREIE Index reached 237.7 on April 30, 2021, while the S&P 500 reached 227.4 (see Exhibit 1).

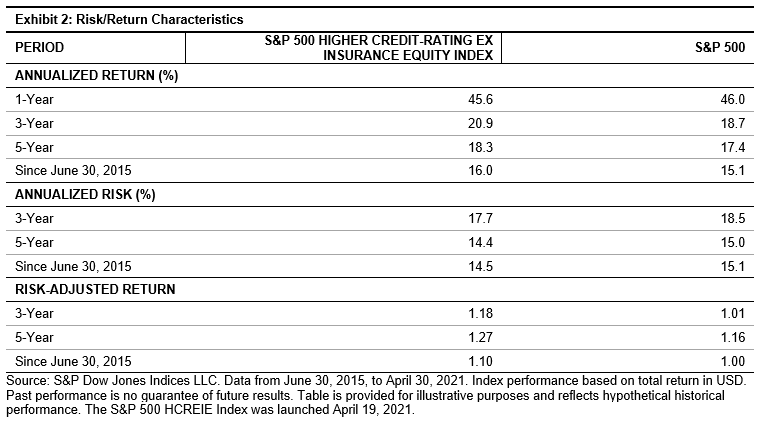

Exhibit 2 shows the detailed risk/return profile of the S&P 500 HCREIE Index versus the S&P 500. Over the studied period, the S&P 500 HCREIE Index outperformed the S&P 500 by 0.87% on an annualized return basis. The reduced volatility helped the strategy deliver a better risk-adjusted return (1.10) than the S&P 500 (1.00). Furthermore, the S&P 500 HCREIE Index also had superior risk-adjusted returns over the three- and five-year periods.

Factor Exposure

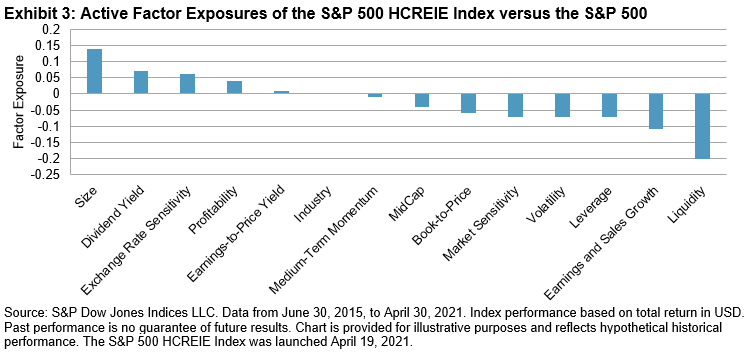

Using the risk factors from a commercial risk model, we present the active exposures5 of risk factors. In comparison with the S&P 500, the S&P 500 HCREIE Index had higher exposures to size, dividend yield, and profitability,6 and lower exposures to liquidity, growth, and leverage (see Exhibit 3). The factor exposure results imply that the constituents in the S&P 500 HCREIE Index tend to be the larger, more mature, and higher quality companies in the S&P 500 universe.

Conclusion

To capture the credit risk premium in the equity market, the S&P 500 Higher Credit-Rating Ex Insurance Equity Index selects stocks with higher long-term credit ratings at or above of ‘A-’/‘A3’. Factor exposure analysis shows that the index constituents tend to be larger, more mature, and higher quality companies. Moreover, the S&P 500 HCREIE Index had better return and risk-adjusted return than the S&P 500 during the period studied.

1 Avramov, Doron, Chordia, Tarun, Jostova, Gergana, and Philipov, Alexander, Credit Ratings and the Cross-Section of Stock Returns (2009). EFA 2008 Athens Meetings Paper, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=940809.

2 If long-term issuer defaulting rating is not available, then senior unsecured debt rating is used as a proxy.

3 See the S&P 500 Higher Credit Rating Ex Insurance Equity Index Methodology for more details.

4 Regulation 114 is the Official Compilation of Codes, Rules and Regulations of the New York State Insurance Department (NYSID). Regulation 114 Trusts are created under a relatively standard form of tripartite agreement involving a single ceding insurance company, i.e. the beneficiary; a financial institution, i.e., the trustee; and a single non-admitted reinsurer, i.e., the grantor, who grants the beneficiary control over the ceded premiums.

5 Active factor exposure is defined as the strategy factor exposure minus the benchmark factor exposure.

6 Refer to Axioma United States Equity Factor Risk Models for more information about factor definitions.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.