Modern Portfolio Theory tells us that higher returns tend to be associated with higher risk. Active managers tend to boast about their risk management skills and claim that they can generate higher returns than passive funds on a risk-adjusted basis. The Risk-Adjusted SPIVA® Scorecard assesses the risk-adjusted returns of actively managed funds against their benchmarks on both a net-of-fees and gross-of-fees basis. Volatility, calculated as the standard deviation of monthly returns, is used as a measure of risk, and performance is evaluated by comparing return/volatility ratios.

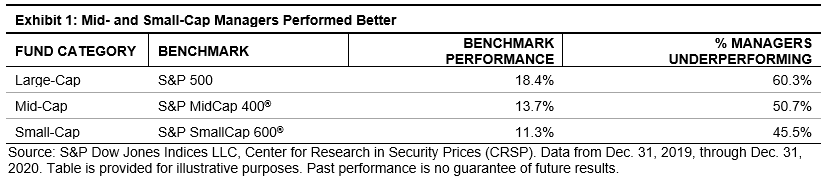

The Risk-Adjusted SPIVA Year-End 2020 Scorecard shows that the significant level of volatility and positive returns of the broad U.S. equity market in 2020 did little to help the case for active managers’ performance. After adjusting for risk, most actively managed domestic funds across market-cap segments underperformed their benchmarks on a net-of-fees basis over mid- and long-term investment horizons. Even on a gross-of-fees basis, the number of outperforming segments declined over time; small-cap value and real estate funds were the only two categories that outperformed their benchmarks over the 20-year period.

For comparison, in Exhibit 2, we listed the performance statistics of active equity funds relative to their benchmarks, both on an absolute return basis (as presented in the SPIVA U.S. Year-End 2020 Scorecard) and on a risk-adjusted basis. Over the 20-year period, fewer than 15% of actively managed funds were able to outperform across any of the three categories, whether the returns were adjusted for risk or not.

Exhibit 3 further confirms that, even within each capitalization segment, little evidence was found to support the theory that higher returns are associated with higher risk. Plotting the annualized returns and annualized volatility of individual funds in scatter plots, we found weak correlations and no trend between these two variables, indicating the difficulty to generalize active managers’ risk management skills as a group. The yellow dots in Exhibit 3 represent the annualized return and volatility of the three benchmarks. Clearly, the benchmark produced higher returns than most active funds at the same level of volatility.

Conclusion

Although active managers claim that their risk management skills are superior to passive investment strategies, their claim does not stand the test of historical statistics. The Risk-Adjusted SPIVA Year-End 2020 Scorecard shows that our SPIVA Scorecard results also hold on risk-adjusted basis. Most active funds lagged their benchmarks in the long term, and we found little evidence to support the assumption that higher risks were rewarded by higher returns.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.