While everyone has been concerned about the inverted yield curve, the CBOE Volatility Index® (VIX) has been under the 21-trading-day realized volatility of the S&P 500 since Aug. 16, 2019. Since volatility traders care not only about what is expected but also what actually transpired, the spread between implied volatility and realized volatility is one of the most important gauges for them to keep an eye on.

Historically, implied volatility tends to stay above realized volatility due to the skewed distribution of stock returns. When implied falls below realized, it usually suggests option premiums are relatively cheap, therefore favoring option buyers.

Implied volatility represents the current market price for volatility, or the fair value of volatility based on the market’s expectation for movement over a defined future period of time. VIX is arguably the most-followed gauge of the U.S. equities market implied volatility in the next 30 calendar days.

Realized volatility, on the other hand, is the actual movement that occurred in a given underlying over a defined past period. For VIX, that underlying is the S&P 500. Since the S&P 500 trades only when the market is open, the convention is to compare VIX with the realized volatility from the previous 21 trading days, approximately one calendar month.

Calendar-year averages since 2000 show that it is “normal” when VIX is above the realized volatility of the broad equity market (see Exhibit 1). The spread, calculated as VIX minus the 21-trading-day realized volatility of the S&P 500, is usually around 3-4 points. It tended to narrow during periods of market turbulence (e.g., in 2000 and 2008); 2008 was the only year that average VIX readings, which were higher than usual, fell short of the realized volatility. On the contrary, while the 2017 VIX level was lower than usual, the relationship between implied and realized volatility remained fairly “normal.”

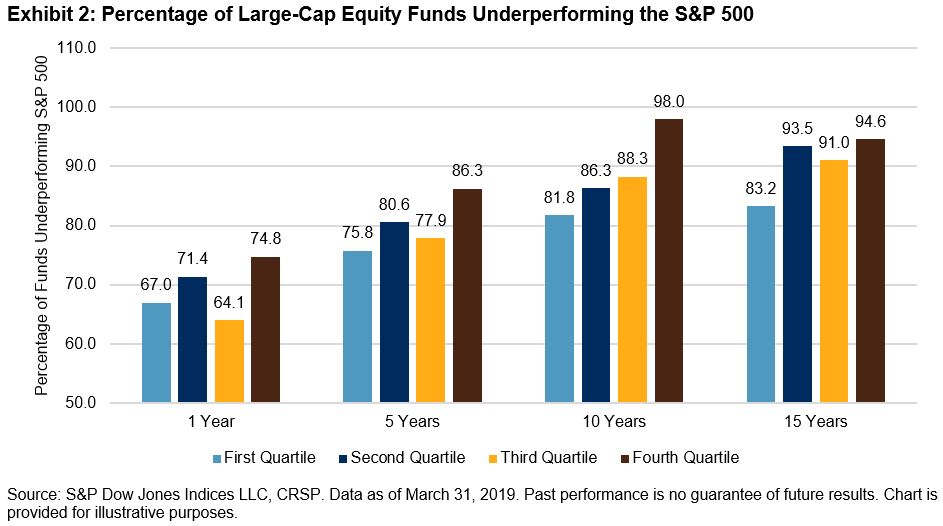

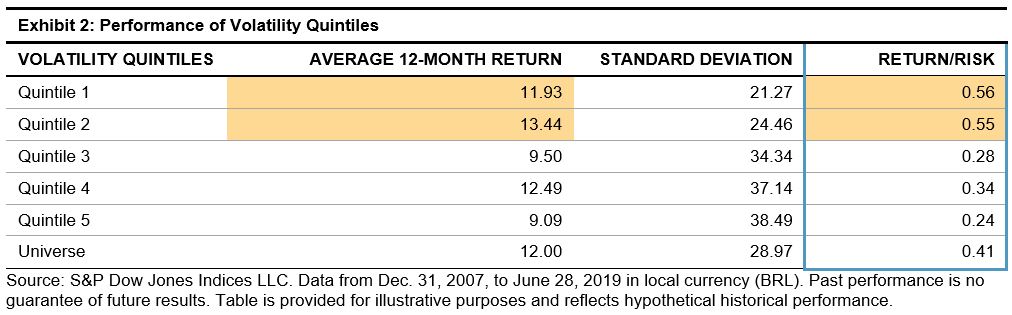

On a day-to-day basis, if we marked all the days as 1 when VIX was higher than the realized volatility and as -1 when VIX was lower than the realized volatility, we can visualize the frequency of positive and negative implied/realized volatility spreads over the past 20 years (see Exhibit 2). Since July 1, 1999, negative spreads occurred on 796 days out of 5,070 (15.7% of the time). Prolonged periods of negative spreads tended to occur in turbulent markets such as those in 2000 and 2008. The most recent stretch of negative spreads occurred from Q4 2018 to early 2019 during the market sell-off.

Why is implied volatility normally higher than realized? From a behavioral finance perspective, this is an indication of risk aversion—investors are willing to pay a premium to buy protection against risk. From an option pricing perspective, it is because stocks and stock indices do not follow the log-normal distribution assumption of Black-Scholes. The empirical distribution of stock returns has a negative skew and hence reflects larger losses than a normal or log-normal model using the ex-post mean and standard deviation would predict. Implied volatility takes into account large but rare events, while realized volatility will only include such events if they have occurred in the look-back calculation period. Since low-probability events are rare by definition, realized volatility tends to understate the potential for large losses most of the time. However, in a distressed market, realized volatility tends to overstate the risk of large losses when these sudden moves indeed occurred in the calculation window.

Why is implied volatility normally higher than realized? From a behavioral finance perspective, this is an indication of risk aversion—investors are willing to pay a premium to buy protection against risk. From an option pricing perspective, it is because stocks and stock indices do not follow the log-normal distribution assumption of Black-Scholes. The empirical distribution of stock returns has a negative skew and hence reflects larger losses than a normal or log-normal model using the ex-post mean and standard deviation would predict. Implied volatility takes into account large but rare events, while realized volatility will only include such events if they have occurred in the look-back calculation period. Since low-probability events are rare by definition, realized volatility tends to understate the potential for large losses most of the time. However, in a distressed market, realized volatility tends to overstate the risk of large losses when these sudden moves indeed occurred in the calculation window.

Nevertheless, in the relationship between implied and realized volatility, realized volatility serves as the baseline, while implied volatility defines the relative values of option premiums. The negative spread between VIX and realized volatility reflects overall complacency in the market.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.