S&P DJI’s Mid-Year 2019 Persistence Scorecard may offer a hint of encouragement for active fund managers. Performance persistence, measured over the three-year period ending March 2019, rose from prior periods. Among the domestic equity funds that were in the top quartile as of March 2017, 11.36% were able to go on and maintain their top-quartile status in the subsequent two years. This figure is a substantial increase from six months prior (7.09%) or even one year prior (2.33%).

However, further study of these top quartile funds shows that it is not enough for active managers to stay ahead of the game with one’s peers; the challenge of beating the benchmarks has intensified.

Using the same methodology as the S&P Persistence Scorecard, we first identified the domestic equity funds that made top quartile status as of March 2017 according to their annualized returns from the prior three-year period. These are the same top quartile funds that we refer to in this blog. We then compared these funds with the universe of all domestic equity funds and the broad market benchmark, the S&P Composite 1500®.

Our goal was to examine whether the top quartile status of active funds led to future outperformance relative to their peers and to the benchmark.

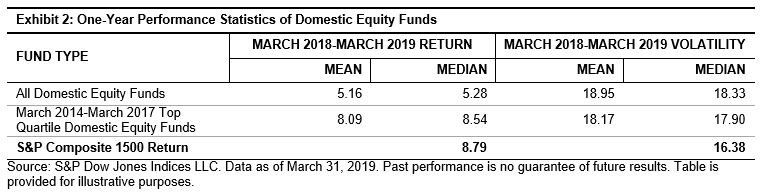

Only a fraction of these original top quartile funds managed to stay in the same league for the two subsequent consecutive years. However, the final top quartile funds displayed some remarkable characteristics. First, they collectively navigated the seesawing market conditions of the past year better than their peers. As shown in Exhibits 1 and 2, these funds generated approximately three percentage points of extra returns, as measured by the mean and median. On average, their annualized volatility was 0.78 percentage points lower than that of the peer group category. Exhibit 1 also shows that the risk/return profiles of these funds were more homogenous than the peer group category; the standard deviations of return distribution and volatility distribution were smaller in this group of funds.

However, the advantage of these top quartile funds disappears once we compare them with the benchmark. The S&P Composite 1500 returned 8.79% with 16.38% volatility during the trailing 12-month period ending March 2019. Compared to the benchmark, the top quartile funds on average returned 70 bps less with 179 bps higher volatility in the same period when compared with the benchmark (see Exhibit 2). In other words, beating the benchmark remained challenging even for managers that ranked high in their peer group category.

For more information on how fund performance persisted, read our latest Persistence Scorecard.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.