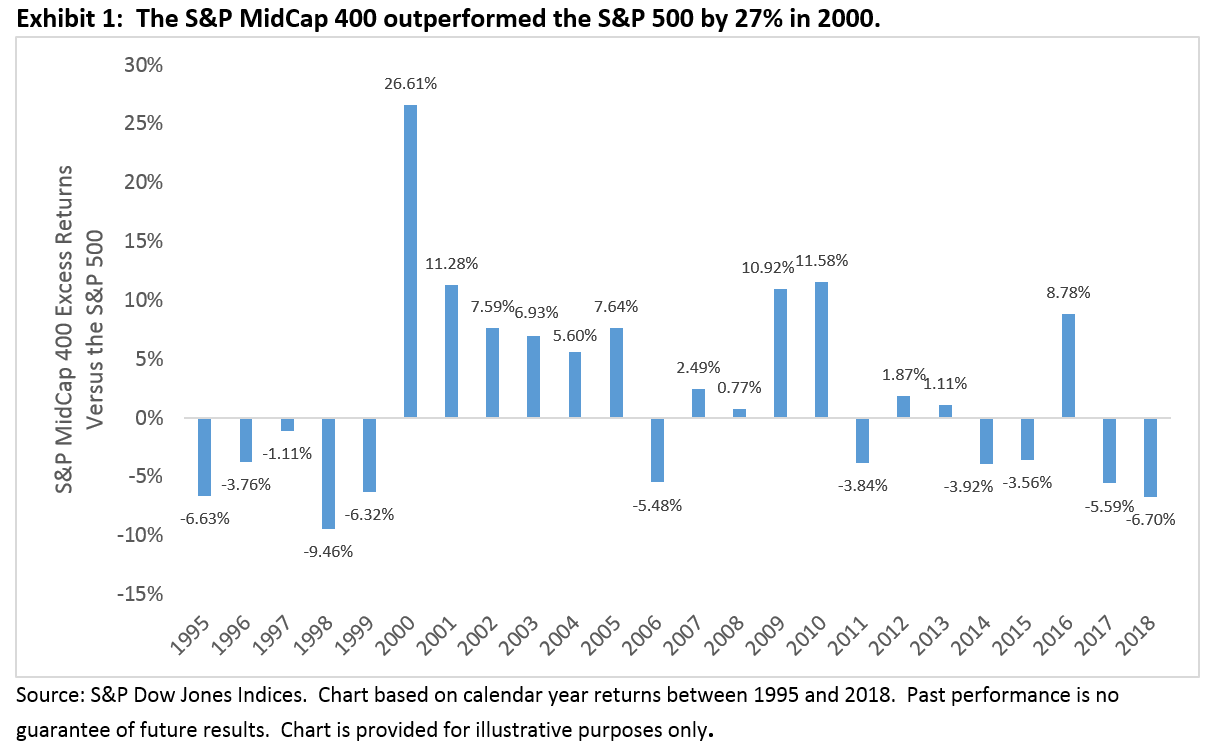

U.S. mid-cap equities – as represented by the S&P MidCap 400 – outperformed both their larger and smaller counterparts since the early 1990s. In decomposing relative returns, sector analysis can be useful to understand the drivers of performance. For example, the S&P MidCap 400’s underweight position in Information Technology at the start of the 21st century helped it beat the S&P 500 by a stonking 26.61% in 2000, the year the Tech Bubble burst.

While sector allocations contributed to the S&P MidCap 400’s excess returns in 2000, the performance of mid-cap I.T. stocks also helped: the mid-cap benchmark’s Information Technology sector fell 4.7% in 2000 compared to a 40.9% plunge by the corresponding S&P 500 sector. So which effect was more important in explaining the mid-cap index’s outperformance – its sectoral allocations or the selection of stocks within each sector?

Conventional Brinson attribution analysis suggests that stock selection was typically around three times more important than sector allocation. To help illustrate this, we constructed two hypothetical portfolios that rebalance at each year end. The “constituent match” portfolio combines the capitalization-weighted S&P MidCap 400 sector indices in proportions that match the S&P 500’s sector weights. The hypothetical “sector match” portfolio combines the capitalization-weighted S&P 500 sector indices in proportions that match the mid-cap index’s sector weights. Exhibit 2 shows the cumulative total returns for these two hypothetical portfolios, as well as for the S&P 500 and the S&P MidCap 400, since December 1994.

Quite clearly, the hypothetical “constituent match” portfolio offered almost identical return streams to the S&P MidCap 400; changing sectoral allocations did not have a material impact on relative returns. Instead, stock selection within each sector was far more important in explaining the S&P MidCap 400’s outperformance; the “sector match” portfolio’s returns was much closer to the S&P 500. Similar results were also observed when comparing the mid-cap index to the S&P SmallCap 600.

The relative importance of stock selection suggests that mid-cap companies may possess a strategic advantage relative to firms within different size ranges. Indeed, mid-caps have generally overcome the risks of small-cap companies while remaining nimble enough to take advantage of growth opportunities that may be unavailable to their large-cap counterparts.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.