I have a confession – earning the market return minus expenses does not feel very enticing. Reasonably well-run index funds will do just that, and probably land within the 2nd or 3rd performance quartile year in and year out. But is that the best I can do? Where’s the satisfaction? My inner Captain Kirk wants an investment that will crush the market.

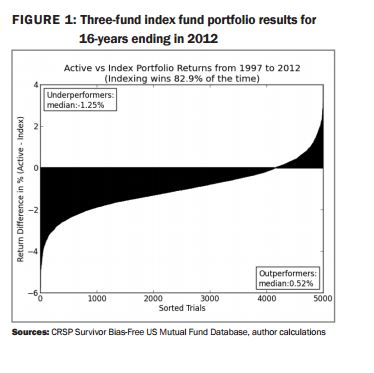

On the other hand, my inner Spock guides me to observe empirical data and apply logic. And Mr. Spock is telling me that if I want to compound returns effectively over time, which is the only way I know of to grow wealth, indexing is my friend. Here’s why:

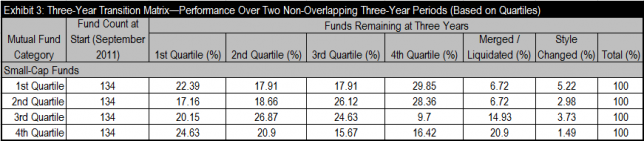

Look at the odds. In every period there are some active managers that outperform the market. But the chances of picking a manager that outperforms in the next period and into future periods are quite slim. Here’s a table showing results of active small-cap funds from our December 2014 issue of Persistence Scorecard:

Almost 30% of 1st quartile small-cap funds, as of September 2011, had fallen to the 4th quartile as of September 2014. Only 22% repeated their 1st quartile performance. Random odds would give a 25% chance if funds did not close, merge, or liquidate. The persistence data shows that active small-cap managers tend to move about in terms of their relative standing. It’s quite likely that if one is fortunate enough to invest with a 1st quartile manager in one period, the manager may fall in performance rankings in future periods.

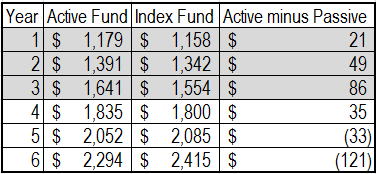

Do the arithmetic of compound returns. I downloaded 3-year annualized total returns, as of April 2015 based upon monthly data, of small-cap active and passive mutual fund share classes in the Morningstar database. My sample is not adjusted for survivorship, so active returns appear better than actual experience. I then created a hypothetical example showing the impact of investing $1000 and earning the median of 1st quartile returns (the 87.5th percentile) of active small-cap share classes for a 3-year period, and earning the median of 4th quartile returns (the 12.5th percentile) of active small-cap share classes for the following 3-year period. I compared this investment with another where I invested $1000 and earned the median 3-year annualized return (the 50th percentile) of all small-cap index fund share classes for six years. Here are the results of my hypothetical example:

After three years, the active strategy is winning by $86. But by the fifth year the slow and steady median small-cap index fund is out in front by $33. After the sixth year, the active strategy is behind by $121. Maybe earning consistent 2nd – 3rd quartile returns is not so dull after all. In any event, I’m betting that maximizing my chances to “Live long and prosper…” will lead to more lifelong satisfaction than going for short term emotional gratification. Sorry Captain Kirk.

I’m presenting this material, along with some related ideas this Thursday afternoon during a complimentary webinar, “Not All Small-Cap Indices are Created Equal,” hosted by S&P DJI.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.