Three issues surround the debate over the Fed and raising interest rates: why should interest rates be increased? When should they be raised and how can the Fed do it. All three need to be resolved.

Why

The traditional description of Fed policy is “removing the punchbowl when the party gets good.” The Fed’s dual mandate of employment and stable prices is a balancing act between competing goals. With the economy growing, employment rising and unemployment under 6%, attention is shifting to prices. With a more upbeat economy comes expectations of higher inflation and upward pressure on prices and wages. Inflation depends on how aggressively business tries to raise prices. The objective in raising interest rates is lower expectations of future inflation to limit efforts to raise prices. Neither the size nor the growth of the money supply completely determines inflation rates. Those who believe that the money supply is the only factor behind inflation must explain why inflation is currently so low after five years of unusually high money supply growth.

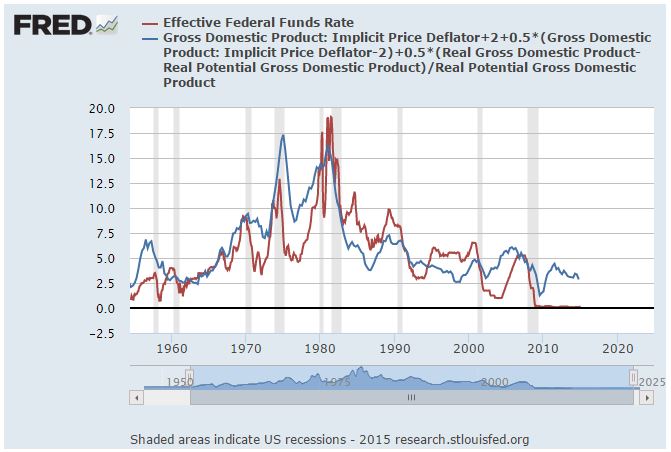

The Fed funds rate affects the economy and financial markets, not just inflation expectations. The Fed’s three rounds of large scale asset purchases – popularly known as QE or quantitative easing – pushed the Fed funds rate to almost zero (see chart) and were a crucial factor in the economic recovery. QE worked by keeping interest rates artificially low and boosting prices of stocks, homes and other assets. However, zero interest rates distort prices and returns in financial markets. With the economy doing better, the Fed wants to normalize interest rates and move the fed funds rate from almost zero to something a bit higher.

A “normal” level for the Fed funds rate depends on inflation, employment and the economy. One widely followed definition of a normal Fed funds rate is the Taylor rule based on analysis of Fed rate setting by John Taylor, a Stanford University economist. The chart, based on calculations of the Taylor rule by the St Louis Federal Reserve Bank, compares the rule to the past and current Fed funds rate, suggesting the the Fed funds rate should be raised. However, the central bank is not in a rush, will probably take small steps of a quarter percentage point at a time.

How

The last time the Fed raised the Fed funds target was July 2006. Back then the level of excess reserves – funds banks have on deposit at the Fed that exceed the level of reserves mandated by law, was small. The Fed funds rate is what banks pay when they borrow or lend reserves to one-another. Before QE, the central bank could sell securities to drain funds from the banking system, raising the cost of borrowing needed reserves. After three rounds of QE, excess reserves are close to $3 trillion, far too large for the Fed to nudge rates higher by selling securities.

With the advent of QE, some questioned whether the central bank would be able to control interest rates until QE was reversed and $3 trillion of reserves somehow vanished. Last fall the Fed announced new operating procedures for managing the Fed funds rate. The ceiling on the Fed funds rate is set by the interest rate the Fed pays banks on excess reserves on deposit at the Fed. With the Fed paying one-quarter percent on excess reserves, there is no reason for a bank to lend overnight to anyone else at a lower rate. The floor is set by reverse repurchase agreements (RRP) where the Fed sells securities and agrees to buy them back at a slightly higher price, the difference determining the interest rate. The availability of RRPs encourages non-banks with funds to invest not to seek a return lower than the RRP rate. Paying interest on reserves has been in place for a few years, the RRP process has been tested. The Fed can manage the Fed funds rate.

When

Friday’s Employment Report of 295,000 jobs added in February is merely the latest piece of strong economic news. The unemployment at 5.5%, also reported in Friday’s Employment data, is in the range that the Fed terms as full employment – it would be nice to see it move lower, but the risk of inflation might move up from here. At the same time, wages are still not rising much, if at all, so there is no immediate reason for the Fed to act. Most forecasts look for the Fed to raise interest rates in the second half of 2015, a few suggest as early as June and some as far away as 2016. Among those Fed members who have comments, the same wide range holds.

Friday also gave the markets a taste of things to come: the Employment Report spooked investors and sent major equity indices tumbling. Zero interest rates can’t go on forever; something that can’t go on forever must, sooner or later, come to an end. The Fed will raise interest rates, no one (not even Janet Yellen) knows when. And, until the Fed acts there will be moments like Friday when the fear of rising rates scares markets.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.