Money is often described has having four functions: store of value, unit of account, medium of exchange and a source of anxiety. Investors reading about the FOMC minutes published earlier this week are focused exclusively on the last function worrying about what will happen when the Fed raises interest rates. A glance at the last two times the Fed shifted from easing to raising rates suggests that these fears are misplaced. As Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren explained in a speech this week, even with some unusual market conditions, the Fed’s shift shouldn’t send markets into turmoil.

The last two Fed tightening moves began in February, 1994 and in June 2004. Both were taken in stride in the economy, the stock market and the foreign exchange markets. The move in February, 1994 was a bit more of a surprise than the 2004 shift. Moreover, in 1994 most Fed Watchers expected the Fed to move slowly and raise the Fed funds rate gradually over several quarters. However the central bank moved more quickly and the faster pace created some disturbance in the mortgage backed securities market. At the same time technology stocks began a five year bull run of mythical proportions.

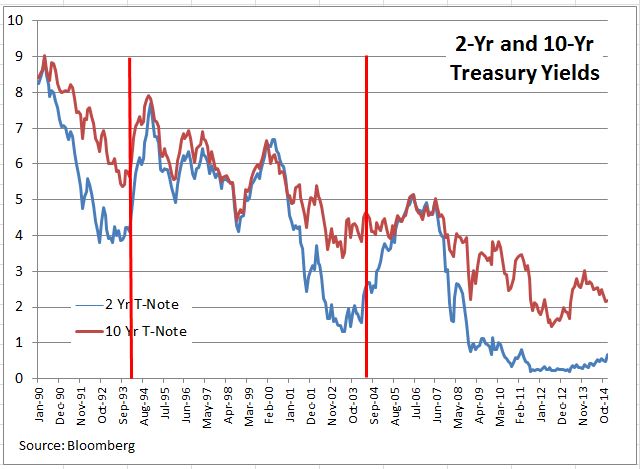

The charts show what happened when the Fed began tightening in 1994 and again in 2004. On each chart the two vertical lines mark the timing of the Fed’s move. The market where a reaction was expected and did occur is the treasury market. Short rates rose, long rates rose but by less and the spread narrowed. When the Fed moves next time it is possible that long rates will move quite a bit. The 10 year T-note yield at about 2% is unusually low and any effort to move the markets back to a more normal condition could more than double the yield on the ten year note.

In both 1994 and 2004 the stock market took the move in stride and continued to advance. The 1994 move did see VIX bounce a bit, but neither move led to a bear market. If the next move is being driven by further declines in unemployment and inflation finally touches 2%, the immediate risk to the stock market is likely to be small.

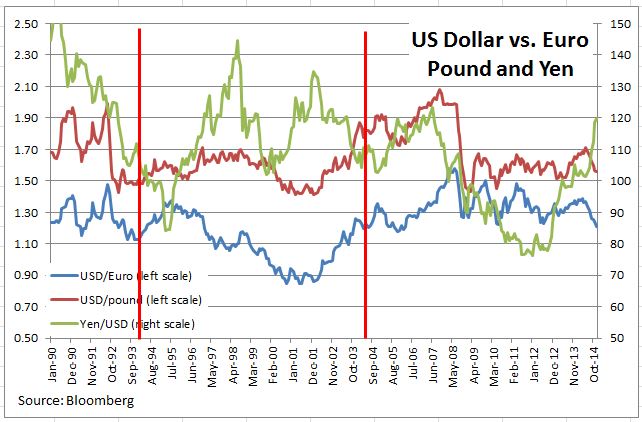

There is some concern at the Fed about how a tightening move may affect foreign economies, especially since they are currently suffering from weaker conditions than in the US. The last chart shows the dollar versus the euro, British pound and the yen. The Fed’s move isn’t likely to change the dollar’s current strength much. However, higher US interest rates could put upward pressure on some foreign interest rates and raise borrowing costs for foreign economies with dollar-denominated debts.

Lest we banish all anxiety about the Fed, think again. The initial Fed move isn’t likely to cause massive damage. However, the Fed’s first step will probably be followed by further tightening and the cumulative effect will grow. For investors the message of the data is not to panic at the Fed’s first tightening move, but not to ignore it either.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.