Our most recent Persistence Scorecard shows that relatively few funds can consistently stay at the top. Out of the 557 domestic equity funds that were in the top quartile as of March 2016, only 2.33% managed to stay in the top quartile at the end of March 2018. That means out of the 2,228 domestic equity funds that were in the opportunity set at the start of March 2015, 557 made it to the top quartile by the end of March 2016. Out of those 557, 45 (8.08%) remained in the top quartile at the end of March 2017. By March 2018, only 13 (2.33%) of those 45 funds managed to stay in the top at the end of March 2018.

One inquiry we often receive from readers is regarding the degree of performance persistence throughout time and whether it varies over time. In other words, how do the current report’s findings compare to previous reports? Are the current persistent scores better or worse than the historical figures?

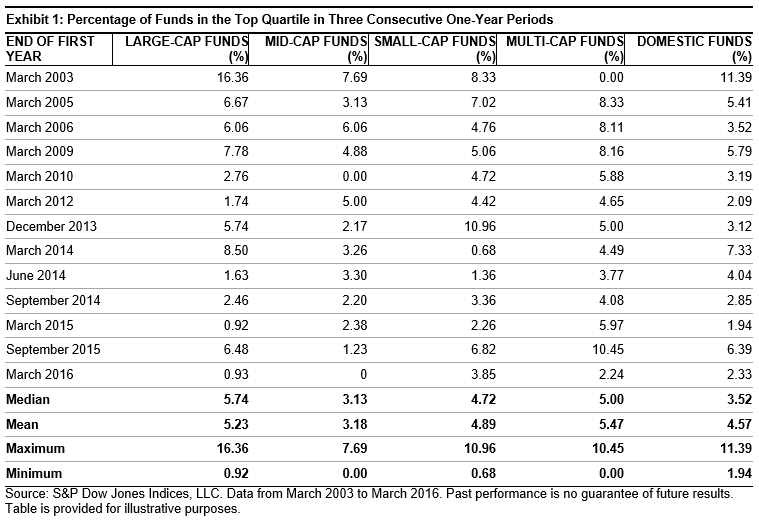

To answer these questions, we take a step back through time to revisit historical reports and summarize the results. Exhibits 1 and 2 show the percentage of funds that managed to remain in the top quartile for three consecutive one-year periods. For example, among all the large-cap funds, 16.36% managed to stay in the top quartile for three straight years starting in March 2003 and ending in March 2005, respectively, while only 6.67% managed to do so in the three years starting in March 2004 and ending in March 2006.

The data show a few interesting findings. The performance persistence of large-cap and mid-cap funds show a long-term downward trend. For example, at the end of March 2003, based on the three prior consecutive years, 16.36% of large-cap funds and 7.69% of mid-cap funds remained in the top quartile. We find that those were the highest performance persistence figures.

We also find that among the domestic equity categories, for funds that were in the top quartile as of March 2016, the percentage that managed to stay in the top quartile in the next two consecutive years is lower than its historical mean and median. The data indicate that persistence scores for March 2018 are significantly lower than those from six months prior for all of the fund categories.

This decline in performance persistence could be partially explained by the volatility and the market shocks experienced in Q1 2018. Funds that had been outperforming in the past might not be able to adjust quickly enough, or the investment style might not be suitable for the new market conditions.

In conclusion, a review of the performance persistence figures over time shows a downward trend over the longer-term horizon for equity funds, indicating an increasing difficulty to stay at the top.